Gabriel Byrne is not a typical film star. From his breakthrough as the lustful and doomed Uther Pendragon in Excalibur, via his iconic Prohibition-era gangster in the Coen brothers’ Miller’s Crossing and the wickedly twisty The Usual Suspects, the Irishman has evaded the usual, overexposed trappings of celebrity, remaining a familiar, respected, but largely private figure.

All of which makes this one-man evocation of his childhood and early life, based on his 2020 memoir of the same name, something of a revelation: not for its scandal or behind-the-scenes gossip – there’s none of that – but of a man who’s a brilliant writer, far funnier, warmer and soulful than the majority of his characters have allowed us to see.

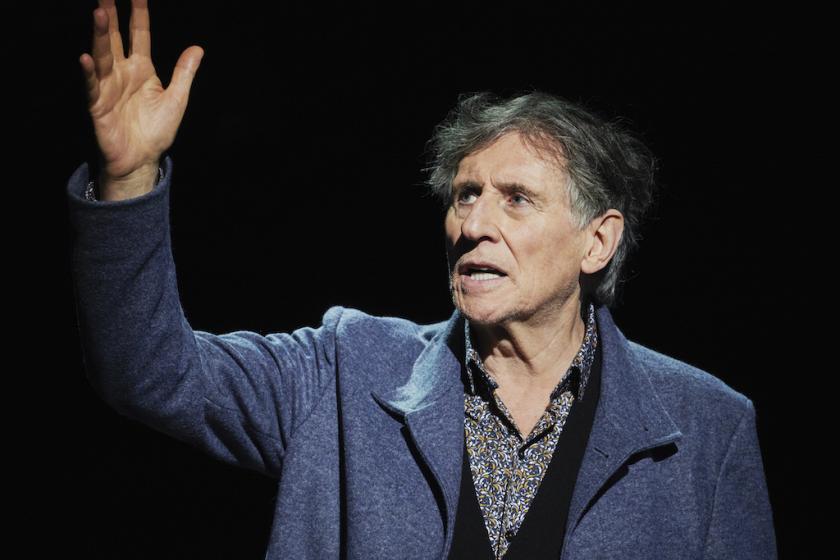

The production is directed by the American stage director Lonny Price, something of a Sondheim specialist. With minimal staging (a stool, bench, small desk and chair), Price’s contribution seems largely to have been to leave it to the actor, perhaps so as to enable Byrne to pace and navigate two hours of text and shifting emotional registers.

As the title suggests, the premise of his reminiscence is the search for the ghosts of his past, in particular the “ghost boy, always running” which is himself. Living in New York, he dreams of Dublin, the city of his birth, a place where “every sight and sound was a marvel”. When he returns, the factory, cinema, church of his neighbourhood have all gone, and he feels like “an intruder in my own past”. But he is flooded by memories, or perhaps of unfinished business.  What follows is a series of brilliantly rendered vignettes, with Byrne adeptly playing all of the characters of his recollection, including both his mother and father, the nun presiding over his Catholic school, and an assortment of eccentric local characters, which enables neat vocal switches, physical comedy and vivid description, such as that of a local woman and terroriser, “her teeth a row of refrigerators in her mouth”.

What follows is a series of brilliantly rendered vignettes, with Byrne adeptly playing all of the characters of his recollection, including both his mother and father, the nun presiding over his Catholic school, and an assortment of eccentric local characters, which enables neat vocal switches, physical comedy and vivid description, such as that of a local woman and terroriser, “her teeth a row of refrigerators in her mouth”.

The childhood seems marked by poverty, Catholicism and the love and resourcefulness of his mother. Byrne’s description of his shame when seeing himself in a clothes shop mirror, his own hand-me-down rags in stark contrast to the school uniform his mum has scrimped and saved to buy him, and of his dilapidated, flea-ridden home, are enormously affecting. But he contrasts these with moments of happiness and delight, including his first visit to a fairground, and of going to the “lovely dark womb of the cinema” with his grandmother: sitting in the direction of the audience and before an imaginary screen, Byrne lights his face from within with wonder and excitement, the 72-year-old playing his pre-adolescent self in a remarkable feat of transformation.

The evening takes a darker turn when the young Byrne attends a seminary in England, where he is sexually abused by one of the priests, an experience he had “cemented over” for years. Flashing forward to his older self at his desk in New York, locating and confronting the priest by phone, he reveals the wash of confusion, anger and pain that would resonate with so many victims of abuse.

He reverts to comedy again, as his failed attempt at the priesthood leads to a return to Dublin and a hapless course through an assortment of jobs – plumber, washer-upper, toilet attendant – until a friend suggests amateur dramatics, and his life is changed. After a sweet and hilarious account of the amdram life, a brief mention of his early fame as an Irish TV heartthrob, and an encounter with Richard Burton – two boozers drawn together at the Venice film festival – Byrne stops short of entering the bulk of his career. For Walking with Ghosts isn’t about that; it’s about dealing with those ghosts, which include the tragic death of his sister, his decades-long alcoholism, perhaps the guilt many feel at leaving their roots behind them.

One wonders about Paul Weston, the troubled psychiatrist he played so well for three seasons of the acclaimed In Treatment, between 2008-10. Weston was a man struggling to deal with other people’s problems while beset by his own demons. And Byrne played him as Irish. Could that experience have set him on the trail that has led to this brave, exposing performance?

Either way, he’s shown a West End audience what we’ve been missing, a performer who can mix the light and the dark, the comic and searingly dramatic, with enormous skill, charisma and grace.

Add comment