Volcano: Noël Coward's Caribbean Play | reviews, news & interviews

Volcano: Noël Coward's Caribbean Play

Volcano: Noël Coward's Caribbean Play

As a rare play is exhumed, the playwright's biographer explains its genesis in Jamaica

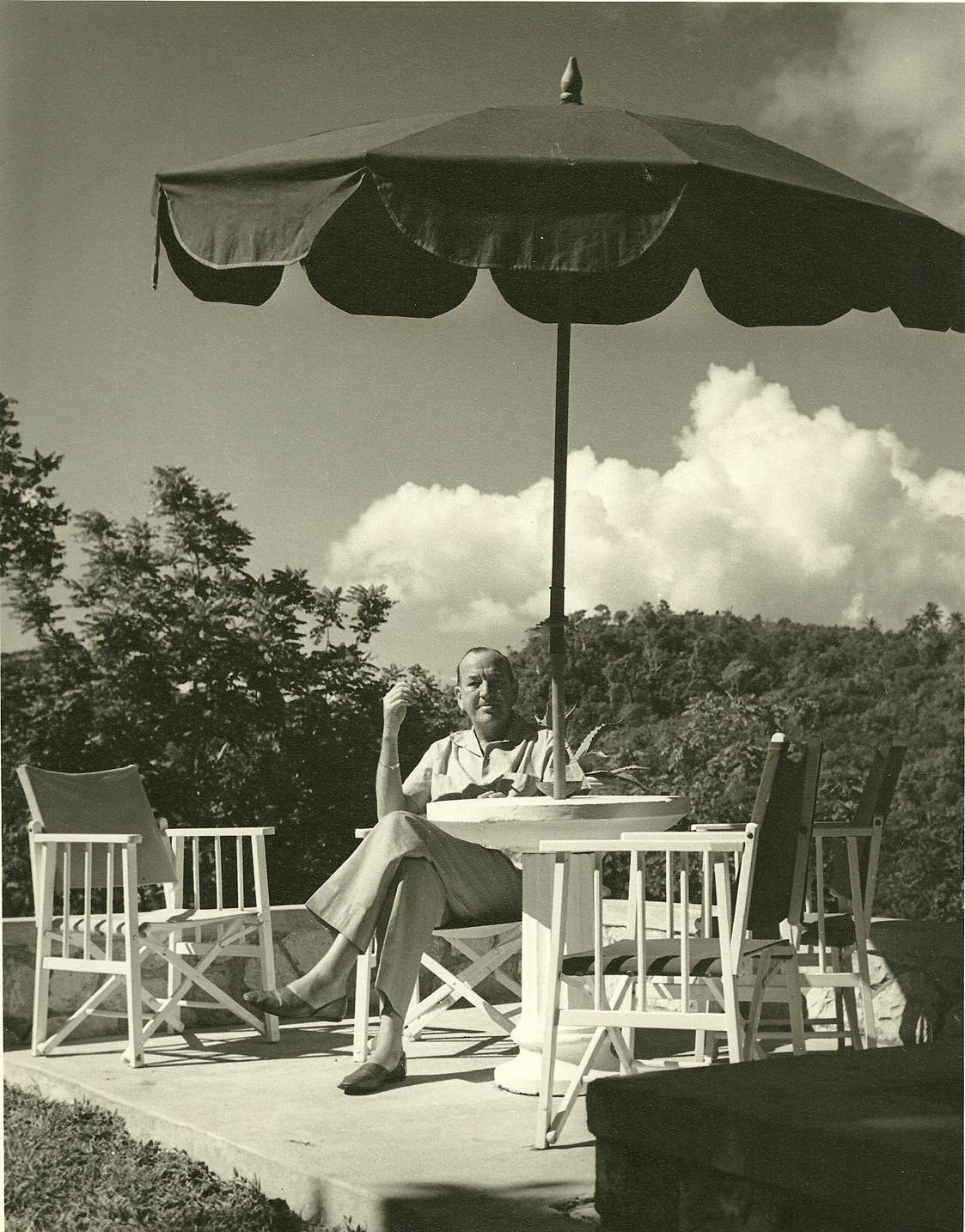

Volcano was written in 1956 when Noël Coward was suffering the dubious status of having become Britain’s first celebrity tax exile. The play – unperformed in his lifetime - is the product of his laidback life in Jamaica, and of a period during which he was regarded as a crumbling colonial relic outmoded by a post-war Labour government and the rowdy commotions of the Angry Young Men back home.

Coward’s reputation had taken a battering in the post-war years. The British public were no longer satisfied with reruns of Brief Encounter, and critics such as Beverley Baxter posed the question, "Did Noel Coward survive the war?" Coward seemed to be a casualty of revolution, and he had retreated to his island paradise to lick his wounds.

In Volcano he proved that he had taken on board the radical new changes of the post-war world, but that his work had pre-empted those changes. As he wrote Volcano, he was in the process of becoming a Las Vegas cabaret star, posing surreally in the Nevada desert in an evening suit with a cup of tea, a cross between Bryan Ferry and Elvis. One might say he had more image changes than Lady Gaga. And Volcano is an explosive example of the manner in which he could confound his critics.

Coward had based its sexual intrigue on a real-life situation

On Samola, a fictional Caribbean island but all too evidently Jamaica, a widow in her early forties, Adela Shelley (Jenny Seagrove in a new touring production), is faced with the ghosts of her passionate past when Guy Littleton (Jason Durr, pictured below with Seagrove), a handsome Lothario, returns on a visit - and in the process seduces a young married woman, Ellen Danbury. When their respective spouses arrive, the plot is further complicated.

The play’s overt discussion of sex was not what Coward’s now middle-aged audiences expected of him. His producer, Binkie Beaumont, turned it down on grounds of its construction; but may have envisaged problems getting it past the censors of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office (an old enemy for Coward). Then Katharine Hepburn, whom Coward had hoped would play Adela, turned it down too. But the more pressing reason for the shelving of Volcano was the fact that Coward had based its sexual intrigue on a real-life situation.

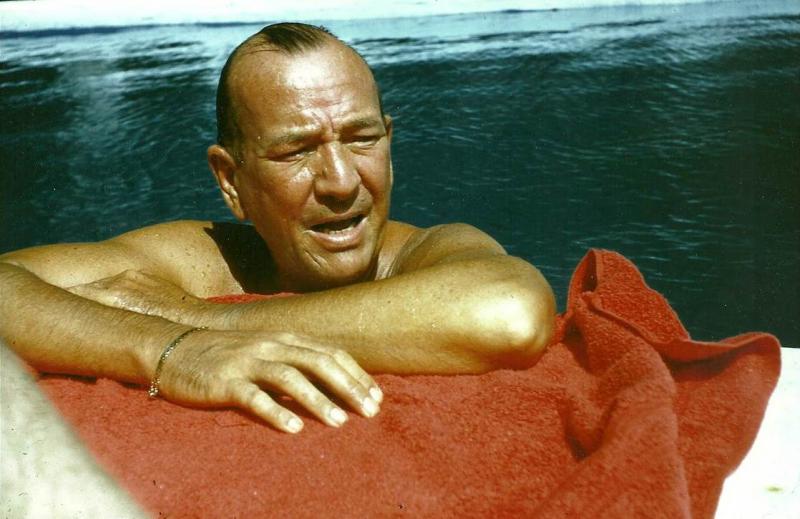

Coward’s Jamaican home, Blue Harbour, and his clifftop chalet, Firefly, were set on the fashionable, if not louche north coast of the island, a veritable ants’-nest of celebrities, from Ivor Novello and Edward Molyneaux to Claudette Colbert, from Bette Davis and Clara Bow to Errol Flynn.

In the days before cheap air travel, celebrities here were left unbothered by the plebeian hordes – and the paparazzi – to carry on their affairs in private. Days would be spent idling by the pool over rum punches; evenings driving to neighbouring villas to drink more rum and eat supper served by silent, white-coated black servants who could be relied upon to keep their own counsel.

In the days before cheap air travel, celebrities here were left unbothered by the plebeian hordes – and the paparazzi – to carry on their affairs in private. Days would be spent idling by the pool over rum punches; evenings driving to neighbouring villas to drink more rum and eat supper served by silent, white-coated black servants who could be relied upon to keep their own counsel.

Here Laurence Olivier came to smoke dope and sunbathe naked by Coward’s pool. John Gielgud could be found on the balcony, "admiring his own profile", as one veteran Jamaican writer, Maurice Cargill observed. Coward’s attitude to guests was equivocal. As one of the characters in Volcano says, "The most beautiful thing about having people to stay is when they leave." He relished his solitude in Jamaica – and later built a second house on top of the hill, Firefly – partly because the noise of the sea ended up driving him mad, but also so that he could escape his visitors.

Another guest was Hepburn, who would zoom up the drive in a sports car with Irene Selznick in the passenger seat. When I interviewed Miss Hepburn in her Upper Eastside house in 1992, she told me how she was frustrated by the Master’s lack of interest in exercise. He was more fascinated by the activities of his friends’ and neighbours’ love-lives, it seemed. And none were more intriguing than that of Ian Fleming – who lived close by in his house, Goldeneye - and Blanche Blackwell, the glamorous scion of an old plantation family, at Bolt House.

Her family, the Lindos, had owned property on the island for generations, and were one of the 21 families said to ‘control’ Jamaica. Blanche, born in Costa Rica, had married Joseph Blackwell, scion of the Crosse & Blackwell dynasty, but had divorced him and returned to look after the Lindo banana plantations. She was a dark-haired, feisty, stylish woman – a product of her Irish-Jewish breeding - and Fleming was soon paying court to her.

Her family, the Lindos, had owned property on the island for generations, and were one of the 21 families said to ‘control’ Jamaica. Blanche, born in Costa Rica, had married Joseph Blackwell, scion of the Crosse & Blackwell dynasty, but had divorced him and returned to look after the Lindo banana plantations. She was a dark-haired, feisty, stylish woman – a product of her Irish-Jewish breeding - and Fleming was soon paying court to her.

"He treated women badly," Blanche told me many years later, in her smart Belgravia house, "but I was not the sort of woman to just take it. I think what he liked in me was my willingness to defy him." It was said that she became a literary as well as a romantic muse to him, the model for Pussy Galore in Goldfinger.

At first Blanche (whose son, Chris Blackwell, would go on to found the Island record label, the home of Bob Marley) denied the possibility of an affair with her and Fleming. Determined to stop the rumour, "One night I got on my horse and rode over to his house," she told me. "I said, 'Noel, I know what you think, and it isn’t true.’"

But that summer of 1956, fascinated by the romance developing between his friends, Coward began to work up his themes for Volcano. The volcano of Coward’s play might well have been the wrath of Fleming’s society hostess wife, Anne – the model for Volcano’s Melissa – when she discovered what was happening. But then, she herself was conducting her own affair with the politician, Hugh Gaitskell.

It was a complicated web of intrigue which gave Coward ample material for his play. In Volcano, themes of sexual love clash with those of fidelity and loyalty, all to the ominous rumbling of impending volcanic explosion – which might also be Jamaica’s moves towards independence, less than a decade away, marking the end of the colonial era.

It was a complicated web of intrigue which gave Coward ample material for his play. In Volcano, themes of sexual love clash with those of fidelity and loyalty, all to the ominous rumbling of impending volcanic explosion – which might also be Jamaica’s moves towards independence, less than a decade away, marking the end of the colonial era.

In the play’s decaying hothouse atmosphere – not unlike prime Tennessee Williams - passion itself became a metaphor for a greater decay – the decay of values which Coward diagnosed in the post-war world (pictured right, Dawn Steele as Melissa Littleton). "You wreak too much havoc, swaggering through people’s lives touting your illusion that physical love is 'the one irreplaceable ecstasy’," Adela tells Guy. "I’m tired of the noise you make with your shrill, boastful trumpeting. Please go away and leave me alone." And she dashes to the floor the shells which in real life the scuba-diving Fleming brought Blanche Blackwell as love-tokens from the Caribbean reef. The shattered shells seem to represent the shards into which paradise is about to break.

When researching my authorised biography of Coward, I visited Goldeneye, Blue Harbour and Firefly. Goldeneye is now a luxury resort. Blue Harbour was then a rather rundown guest house – although one could still dally by the pool where Noel’s friends had drunk and gossiped the days and nights away.

Up on the hill stood Firefly, his retreat, looking out over the bay, and the Blue Mountains – and Coward’s own gravestone, since it was here, far from the England that he helped defined, that he died, on 26 March 1973. But down at Bolt House, the same shells that Fleming had gathered for Blanche Blackwell still stood on the shelves, intact and pristine, as if waiting for the story to continue. It was easy to hear the echo of cocktails and laughter in that place - but also to imagine the darker passions that passed between those glamorous figures who drifted through these tropical rooms.

- Volcano is at Theatre Royal Windsor until 2 June, then on tour to Richmond, Bath, Cambridge, Eastbourne, Shrewsbury, Guildford, Oxford, Brighton and Malvern

- Philip Hoare’s book, Noël Coward: A Biography is published by the University of Chicago Press

Share this article

more Theatre

Two Strangers (Carry A Cake Across New York), Criterion Theatre review - rueful and funny musical gets West End upgrade

A Brit and a New Yorker struggle to find common ground in lively new British musical

Two Strangers (Carry A Cake Across New York), Criterion Theatre review - rueful and funny musical gets West End upgrade

A Brit and a New Yorker struggle to find common ground in lively new British musical

Testmatch, Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Testmatch, Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Add comment