Many an Edinburgh Fringe transfer has struggled when it moves to the big city, but the Dirty Hare company’s Gunter, sensibly embedded in the Royal Court’s intimate Upstairs space, has settled in nicely, thanks.

Originally staged at the best Fringe venue for new theatre-making, Summerhall, where it won a Fringe First award last year, Gunter was devised by Lydia Higman (who also plays drums and Fender lead guitar and serves as narrator), Rachel Lemon (who directs) and Julia Grogan (who performs, main picture). Along with the other two women in the cast, Grogan plays the usual multiple roles required by a small-scale but ambitious piece, notably appearing as a central character, an accused witch called Elizabeth Gregory.

The audience arrives to find archive footage of football hooligans projected onto the back curtain. Our narrator tells us she is a historian who has found a story that deserves to be told. The other three actors, dressed in white soccer strip, sing an a cappella song about a “big man who is bigger than me”, a portent of what's to come. It's 1604, a caption on the back curtain tells us, and we are at the Shrovetide football match in an Oxfordshire village.

To ginger up the audience, we are invited to imagine a witch in our mind’s eye, then to throw balls into buckets that Norah Lopez-Holden deftly fields. Until she doesn’t, the ball rolls away and things kick off.  Two boys start insulting the manhood of the player who missed the ball, and Brian Gunter, the richest man in the village, intervenes. Brian, played as a tough Scot by Hannah Jarrett-Scott, doesn’t respond well to anarchy, we are sardonically told: he knocks the two boys’ heads together and they are fatally wounded – ingeniously suggested by the bursting of a big red balloon Jarrett-Scott has been energetically pumping up.

Two boys start insulting the manhood of the player who missed the ball, and Brian Gunter, the richest man in the village, intervenes. Brian, played as a tough Scot by Hannah Jarrett-Scott, doesn’t respond well to anarchy, we are sardonically told: he knocks the two boys’ heads together and they are fatally wounded – ingeniously suggested by the bursting of a big red balloon Jarrett-Scott has been energetically pumping up.

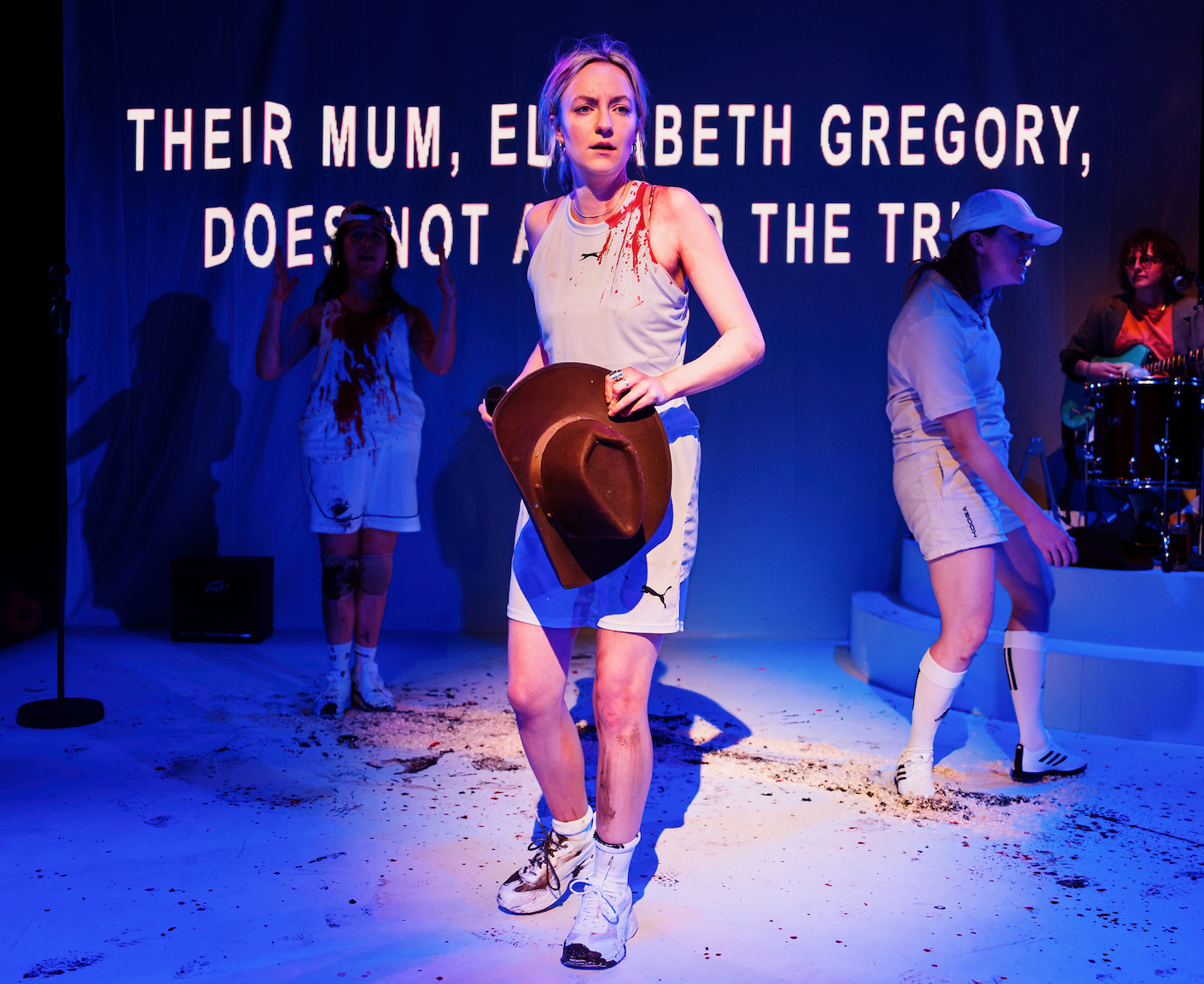

The trial of the richest man in the village for the murders is weighted in favour of his wealth, predictably, and he goes free, soon after declaring football, for which he has a “blind hatred”, illegal. The boys’ distraught mother, Elizabeth, does not attend the trial, a caption tells us; instead, she dons a cowboy hat and sings a country song lamenting their loss. But soon Gunter’s daughter Anne is showing signs of mania, and fingers start pointing at Elizabeth and two of her female friends accused of being witches who have possessed the girls in revenge for the boys’ deaths. If found guilty they will hang; if innocent, their accusers will go on trial instead.

The piece proceeds through its extraordinary story in an episodic way, ending up in the Star Chamber in 1606, its progress punctuated by songs, dancing and Higman’s incidental music, the details researched as far as they can be. (Weirdly, it seems the Gunpowder Plot threw all of the country’s bureaucracy into disarray, and records of many post-1605 trials went missing.) Even so, the story that – the narrator has assured us – “deserves to be told” emerges as a grim tale of misogyny fuelled by the arrival on the throne of James I, the witchfinder king already responsible for hanging 300 witches in Scotland. The text uses modern-day references, too, that bleed into the dialogue, implying that the misogyny of the 17th century is still a force in the land. (I suspect few, if any, people in the audience needed convincing, or actually thought of a witch as a green-faced hag in a pointy hat.)

This is an ingenious staging, making full use of the small space with just portable floor lighting as props and creating shadow figures behind the back curtain. At 70 minutes long, no interval, its format gets a little overstretched, like the various balloons the cast blow up. But they make for very affable, lively company, serving up their subject matter with fine vocals and a chummy, larky kind of humour that prevents the message from becoming preachy. The result is sassy but serious stuff.

Add comment