Turning the Screw, King’s Head Theatre review - Britten and the not-so-innocent | reviews, news & interviews

Turning the Screw, King’s Head Theatre review - Britten and the not-so-innocent

Turning the Screw, King’s Head Theatre review - Britten and the not-so-innocent

Real-life triangle around the composer’s darkest masterpiece yields fitfully strong drama

David Hemmings was, by his own later admission, a knowing and bumptious boy when Britten cast him as the ill-fated Miles in his operatic adaptation of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. The upheaval Hemmings wrought in Aldeburgh’s Crag House when Britten and his life-partner Peter Pears were living there has potential for a similar ambiguity to the opera’s carousel of what’s innocent and what’s “depraved,” and Kevin Kelly has realized the essential drama in it.

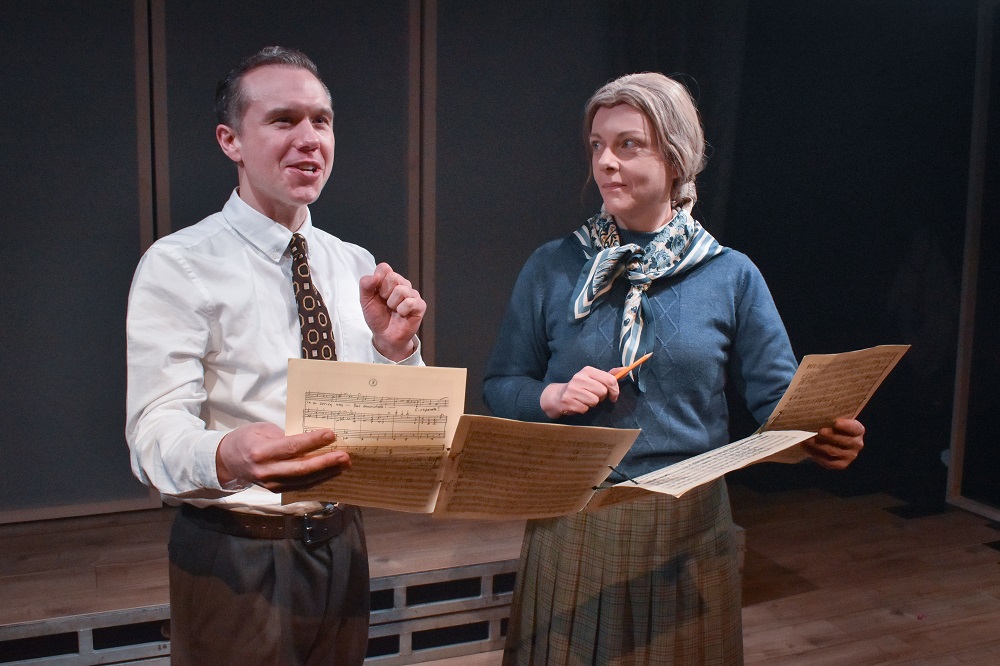

The main problem is that no 12-year-old of unbroken voice was going to act in a more explicit take than the opera’s on who is poisoned victim and who snake given the very tricky issue of pederasty. The solution is as good as it can be: present a well-spoken Hemmings in later life looking back on the best time of his life, the inspiration of working with a great genius, and then let him loose as Master David the cheeky Cockney (from Tolworth?) Liam Watson pulls off the double-act plausibly, and there’s no false note in the acting of the other leads as their characters variously come under his spell – or not, in the case of Peter Pears. Simon Willmont (pictured below, right, with Gary Tushaw as Britten) has the benefit of some of Kelly’s best writing in the strongest dramatic confrontation, Here the boy – described in reality by his older self as “more heterosexual than Genghis Khan”, a curious line which hasn’t found its way in to the play – furiously throws all the prejudice inculcated by his father against “you homos” in the face of Pears’s fatherly concern.  Kelly wants to gain as much sympathy as he can for the difficulties of the musical couple’s way of life at a time – the mid-1950s – before homosexual acts were legalized. Imogen Holst, Britten’s wonderful amanuensis, is propositioned by the composer for a “white marriage” with Pears to keep up appearances, and turns him down with quiet dignity in Jo Wickham’s fine portrayal (strange coincidence: the play Ben and Imo is due to open at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Swan Theatre later this month). Gary Tushaw (pictured below with Wickham) is immensely charismatic as a Britten of infinite variety; the complications of his infatuation with young David are registered in another excellent scene where he, too, becomes a kid in their horseplay. Kelly has a good point in asking who Britten really is within the context of the opera: perhaps the Governess, more sinned against than sinning? For those of us who know the text, the insertion of lines from Myfanwy Piper’s libretto into the mouths of Britten and Pears (who of course created the role of the sinister dead valet Peter Quint) can feel a bit clunky, but the intention is good.

Kelly wants to gain as much sympathy as he can for the difficulties of the musical couple’s way of life at a time – the mid-1950s – before homosexual acts were legalized. Imogen Holst, Britten’s wonderful amanuensis, is propositioned by the composer for a “white marriage” with Pears to keep up appearances, and turns him down with quiet dignity in Jo Wickham’s fine portrayal (strange coincidence: the play Ben and Imo is due to open at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Swan Theatre later this month). Gary Tushaw (pictured below with Wickham) is immensely charismatic as a Britten of infinite variety; the complications of his infatuation with young David are registered in another excellent scene where he, too, becomes a kid in their horseplay. Kelly has a good point in asking who Britten really is within the context of the opera: perhaps the Governess, more sinned against than sinning? For those of us who know the text, the insertion of lines from Myfanwy Piper’s libretto into the mouths of Britten and Pears (who of course created the role of the sinister dead valet Peter Quint) can feel a bit clunky, but the intention is good.

There’s always the danger of packing in too much information: the audience has to be told about the James adaptation, the dangers facing gay couples, the various relationships, and sometimes you feel a hand on your shoulder saying “have you got that?” Least successful is a nightmare scene where Britten is faced with a judge who threatens him with obliteration of his life’s work. Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing pop up somewhat arbitrarily, though Jonathan Clarkson, whose main role is as director Basil Coleman, acts well throughout.  There’s also a “what the heck?” feeling about the composer introducing the boy to his Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra aka Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell, where we leap unfathomably to the later stages within seconds and a bit of mad conducting seems totally out of place. The music – Handel and Vaughan Williams as well as Britten – is well sung when live, but the visuals are weak; it would surely have been better for the strong acting to take place within a black box rather than the flimsy framework which passes for “design”.

There’s also a “what the heck?” feeling about the composer introducing the boy to his Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra aka Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell, where we leap unfathomably to the later stages within seconds and a bit of mad conducting seems totally out of place. The music – Handel and Vaughan Williams as well as Britten – is well sung when live, but the visuals are weak; it would surely have been better for the strong acting to take place within a black box rather than the flimsy framework which passes for “design”.

It might have overburdened the drama to explain that the young man who was Britten’s “Young Apollo” in his first love affair, Wulff Scherchen, was in his late teens to Britten’s early twenties when the relationship was consummated; and a crucial dimension which has always pained me, Britten’s confession to several reliable collaborators that he was raped by a master at his school, isn’t brought in to the picture. Kelly and his director Tim McArthur are clear, as any responsible Brittenites must be, that though the composer might have harboured sexual desires towards pre-pubescent boys, he never acted on them (well, not beyond a kiss, in a relationship obliquely referred to here).

Were it not for the acting, I’d say stick to the chapter “Malo…than a naughty boy” in John Bridcut’s superbly nuanced Britten’s Children (Faber), a major source of lines for Hemmings drawn from the interview conducted in what was originally a television documentary (Kelly fails to give credit in his acknowledgments). But the performers’ hard work, and the ongoing efforts of the King’s Head in its new, underground venue, deserve our support.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Add comment