Lightning hasn't quite struck twice at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, where Trevor Nunn's dazzling reclamation of early Terence Rattigan (Flare Path) has been followed by the same director's transfer from Chichester of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Tom Stoppard's first play. How does this 1966 gloss on Hamlet by way of Beckett hold up today? Engagingly enough, not least when its two tireless leads are in full existentialist flow. But some may nonetheless feel a degree of exhaustion, however much they'll want to cheer Samuel Barnett and Jamie Parker on.

I remember being knocked sideways by this play when I first encountered it in school, which is to record a youthful response to what is clearly a young dramatist's play. But seeing R&G this many years later is to realise that I've moved on and so, clearly, has Sir Tom, who long ago found a way to fold the verbal high jinks and philosophising and wit into plays that tear at the heart even as they linger on in the mind.

Is it fair, then, to criticise this venture for not being Arcadia? Clearly not, except that Stoppard's masterwork - directed in its 1993 National Theatre premiere by Nunn - itself takes on mortality with a wounding grace and ease out of reach of R&G. You admire this earlier play as you might a startlingly precocious talent just beginning to revel in the linguistic showmanship that would become his stock-in-trade. But those hoping to be transported by the sheer rush of language - to feel the ache that an awareness of death brings with it, not to mention the interweaving of love and loss - will have to search elsewhere in the Stoppard canon and simply let two blazing star turns be this R&G's self-evidently bravura reward.

Barnett and Parker were part of the now-legendary original company of Alan Bennett's The History Boys, a National venture whose alumni (James Corden included) are having a field day at present on the London stage. This play, though, stretches its leading men in ways, both vocal and physical, that Bennett's ensemble saga of life in and around the schoolroom didn't go near. Barely offstage for the better part of three hours, the pair debate such issues as order v chaos and determinism v free will amidst a tragicomic landscape that keeps deconstructing itself: Pirandello would have been proud.

Beckett, too, to cite an obvious influence whose presence would hang over this play even if the Haymarket had not hosted two separate engagements of Waiting for Godot in recent years. Dressed in lace-up boots, their outfits at once classical and funky, Barnett and Parker suggest Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as a younger, more febrile Didi and Gogo: two lost souls embarked on a search for meaning only to find themselves bumping up against some chap called Hamlet who can't stop "talking to himself".

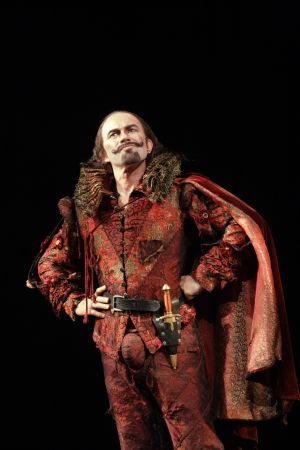

A direct link between Beckett and Shakespeare arrives in the florid, self-aggrandising Player, who sweeps on stage like a healthier Pozzo, his raggle-taggle thesps a collective equivalent to Godot's hapless Lucky. The showiest of R&G's supporting roles, the Player is here taken by Chris Andrew Mellon (pictured right in full, chin-upturned swagger), filling in for Tim Curry, who departed the project for health reasons out of town. All leering eyebrows and flashing teeth, Mellon cuts an unexpectedly sleazy presence in the part, though he should be well prepped to play Captain Hook as and when the next panto season comes around.

A direct link between Beckett and Shakespeare arrives in the florid, self-aggrandising Player, who sweeps on stage like a healthier Pozzo, his raggle-taggle thesps a collective equivalent to Godot's hapless Lucky. The showiest of R&G's supporting roles, the Player is here taken by Chris Andrew Mellon (pictured right in full, chin-upturned swagger), filling in for Tim Curry, who departed the project for health reasons out of town. All leering eyebrows and flashing teeth, Mellon cuts an unexpectedly sleazy presence in the part, though he should be well prepped to play Captain Hook as and when the next panto season comes around.

The actual Hamlet sequences, by contrast, carry a genuine charge not least because the young actor Jack Hawkins on this evidence looks as if he would acquit himself very capably as the Danish prince. (Ditto James Simmons as Claudius, based on the snatches of Shakespeare on view.) But the Bard as co-opted by Stoppard exists merely to fuel the ruminations and fulminations of our central pair, who are afforded a pride of place denied them in Shakespeare's text beyond a mantra ("words, words, words") of which, one feels, Hamlet would surely approve.

Stoppard's words, in turn, are fielded with brio and elan by the principals, the near-pugilistic confidence of Parker's Guildenstern undercut by Barnett's plaintive-eyed Rosencrantz as the two anticipate the "something or someone" that will confer meaning on their plight. Barnett charts the gathering agitation and anger as Rosencrantz gives way to tears, Parker in turn announcing "death as the ultimate negative", well before Shakespeare's play kills Guildenstern off.

Does the verbal dazzle deepen? Not in the manner of the Stoppard plays to come, whereby loquaciousness gives way to something approaching wonder. But as I watched the extended game of very deliberate rhetorical tennis that comes midway through Act I, it occurred to me that there are far worse ways to spend your time if Wimbledon - as some are fearing - is indeed rained out.

Add comment