The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Old Vic Tunnels | reviews, news & interviews

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Old Vic Tunnels

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Old Vic Tunnels

Fiona Shaw becomes a modern balladeer in Coleridge's gripping nautical poem

Here’s an elegant thing to do before eight o'clock dinner - stroll out for an hour’s recital of a rollicking story-poem done by a leading actress in a hip underground venue with judiciously hip application of modern dance, then go off and diss it over your sushi. Very London life.

And if the pleasure potential offered by Fiona Shaw and Phyllida Lloyd in recounting Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s splendid 1798 horror yarn The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is any yardstick, there ought to be a future for a periodic series restoring dramatic poetry to the public at the cocktail hour.

Shaw herself ushers the little audience into the graffiti-bedecked tunnels under Waterloo station as ebulliently as a bride’s mother at a wedding, even though she’s merely dressed in black trews and shirt. It’s a neat device to introduce the poem which tells how a guest arriving at a family wedding is stopped outside by a wizened old mariner who forces him to listen to his ghastly tale of a sea journey cursed by his callous act in shooting an albatross.

She seems to wink at us: maybe the mariner is a conman

Coleridge, who also wrote the probably better-known Kubla Khan, was a magician who could spin the richest silks from simple words and an almost childlike rhythmic tread that lives in the speaking of it aloud. He takes us, along with the detained guest, on an apocalyptic voyage: a ship first trapped in arctic ice, then becalmed in a diabolical heat, where - unforgettably - “water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink”. The mariner, who caused this catastrophe by shooting the sailors’ guardian bird, the albatross, pays for it by watching his 200 companions die while he is doomed, by a game of dice between Death and Life-in-Death, to become Undead.

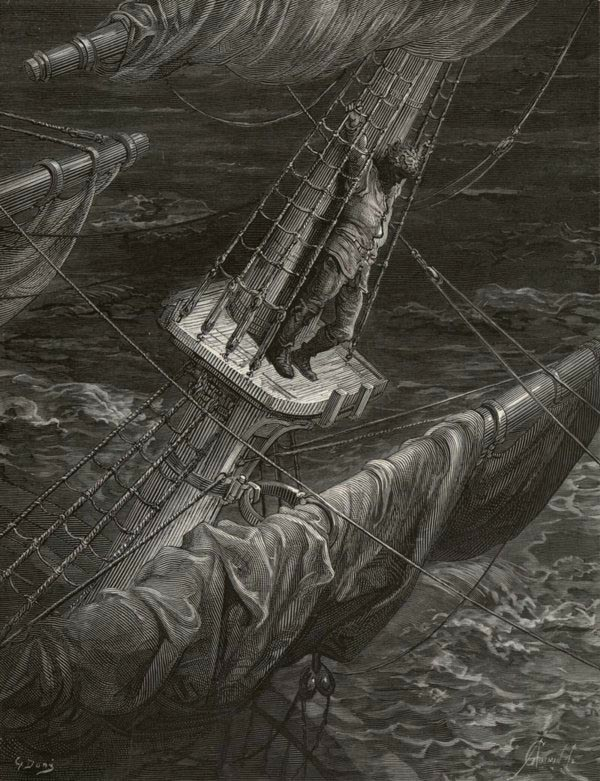

The celebrated 1876 illustrations of Gustave Doré (see picture) have hallowed the poem in romantic spiritualism, but the vernacular simplicity of the verse can’t be disguised, and this seems to be where Shaw and Lloyd headed. Shaw, who can rarely stave irony out of her clever voice, treats the short, iambic lines robustly, almost rustically, more like an observer than the protagonist. She cuts an entertaining androgynous figure, full of Irishness and humour, Technicolor-clear with every phrase and suspenseful pause, but regaling us rather with a shaggy dog story than transmitting nightmare flights of someone losing their mind and staring into Hell before finding moral redemption. She seems to wink at us: maybe the mariner is a conman, and the guest, if he wakes up sadder and wiser in the morn, might keep closer guard on his wallet next time.

The celebrated 1876 illustrations of Gustave Doré (see picture) have hallowed the poem in romantic spiritualism, but the vernacular simplicity of the verse can’t be disguised, and this seems to be where Shaw and Lloyd headed. Shaw, who can rarely stave irony out of her clever voice, treats the short, iambic lines robustly, almost rustically, more like an observer than the protagonist. She cuts an entertaining androgynous figure, full of Irishness and humour, Technicolor-clear with every phrase and suspenseful pause, but regaling us rather with a shaggy dog story than transmitting nightmare flights of someone losing their mind and staring into Hell before finding moral redemption. She seems to wink at us: maybe the mariner is a conman, and the guest, if he wakes up sadder and wiser in the morn, might keep closer guard on his wallet next time.

This was a creation for last summer's Athens and Epidaurus festival, which possibly contributes to a feeling that the staging is over-egged for the Old Vic Tunnels. This venue has its own atmosphere, with its sickly, dripping arches and trains rumbling overhead, and doesn’t need the crepuscular soundscore provided by Mel Mercier (perhaps other venues did).

Shaw races about the little space like an eager cabin boy, tugging at ropes, unfurling sailcloth and climbing mizzenmasts - vivid, she is, to the gunwales. She has a lad with her, the dancer Daniel Hay-Gordon, whom she manipulates as if he were her marionette. She poses him as the mariner one moment, frozen in a traditional crone’s posture, or enacting the albatross, silhouetted in flight, or the young dying sailors, draped in pietà across her. Credited to the fine choreographer Kim Brandstrup, this Doré-esque picture-making exists almost in another era, in spotlights and shadows (lighting by Jean Kalman and Mike Gunning), a fractured silent movie alongside Shaw’s daybright delivery. But again, I wondered if it would have lost much by losing it, and making Shaw carry the whole thing solo, more rawly.

Shaw races about the little space like an eager cabin boy, tugging at ropes, unfurling sailcloth and climbing mizzenmasts - vivid, she is, to the gunwales. She has a lad with her, the dancer Daniel Hay-Gordon, whom she manipulates as if he were her marionette. She poses him as the mariner one moment, frozen in a traditional crone’s posture, or enacting the albatross, silhouetted in flight, or the young dying sailors, draped in pietà across her. Credited to the fine choreographer Kim Brandstrup, this Doré-esque picture-making exists almost in another era, in spotlights and shadows (lighting by Jean Kalman and Mike Gunning), a fractured silent movie alongside Shaw’s daybright delivery. But again, I wondered if it would have lost much by losing it, and making Shaw carry the whole thing solo, more rawly.

It’s well worth reacquaintance with this marvellous yarn, then, which induces a sudden surge of curiosity about what other poetry could be refreshed by modern theatrical balladeers in a thought-provoking slot before dinner. Milton? Goethe? Homer? Still, this particular production could do with less of today’s clever brains and a little more of yesterday’s superstitious soul.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Maiden Voyage, Southwark Playhouse review - new musical runs aground

Pleasant tunes well sung and a good story, but not a good show

Maiden Voyage, Southwark Playhouse review - new musical runs aground

Pleasant tunes well sung and a good story, but not a good show

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Inter Alia, National Theatre review - dazzling performance, questionable writing

Suzie Miller’s follow up to her massive hit 'Prima Facie' stars Rosamund Pike

Inter Alia, National Theatre review - dazzling performance, questionable writing

Suzie Miller’s follow up to her massive hit 'Prima Facie' stars Rosamund Pike

A Moon for the Misbegotten, Almeida Theatre review - Michael Shannon sears the night sky

Rebecca Frecknall shifts American gears to largely satisfying effect

A Moon for the Misbegotten, Almeida Theatre review - Michael Shannon sears the night sky

Rebecca Frecknall shifts American gears to largely satisfying effect

Burlesque, Savoy Theatre review - exhaustingly vapid

Adaptation of 2010 film is busy, bustling - and bad

Burlesque, Savoy Theatre review - exhaustingly vapid

Adaptation of 2010 film is busy, bustling - and bad

Add comment