The Merchant of Venice, BBC iPlayer review – a parable on the limits of tolerance | reviews, news & interviews

The Merchant of Venice, BBC iPlayer review – a parable on the limits of tolerance

The Merchant of Venice, BBC iPlayer review – a parable on the limits of tolerance

Polly Findlay's 2015 take on Shakespeare's trickiest comedy pays dividends

Ah, 2015. Those halcyon days of packed theatres. Thank God the RSC had the presence of mind to film Polly Findlay’s production of The Merchant of Venice, now streaming on BBC iPlayer.

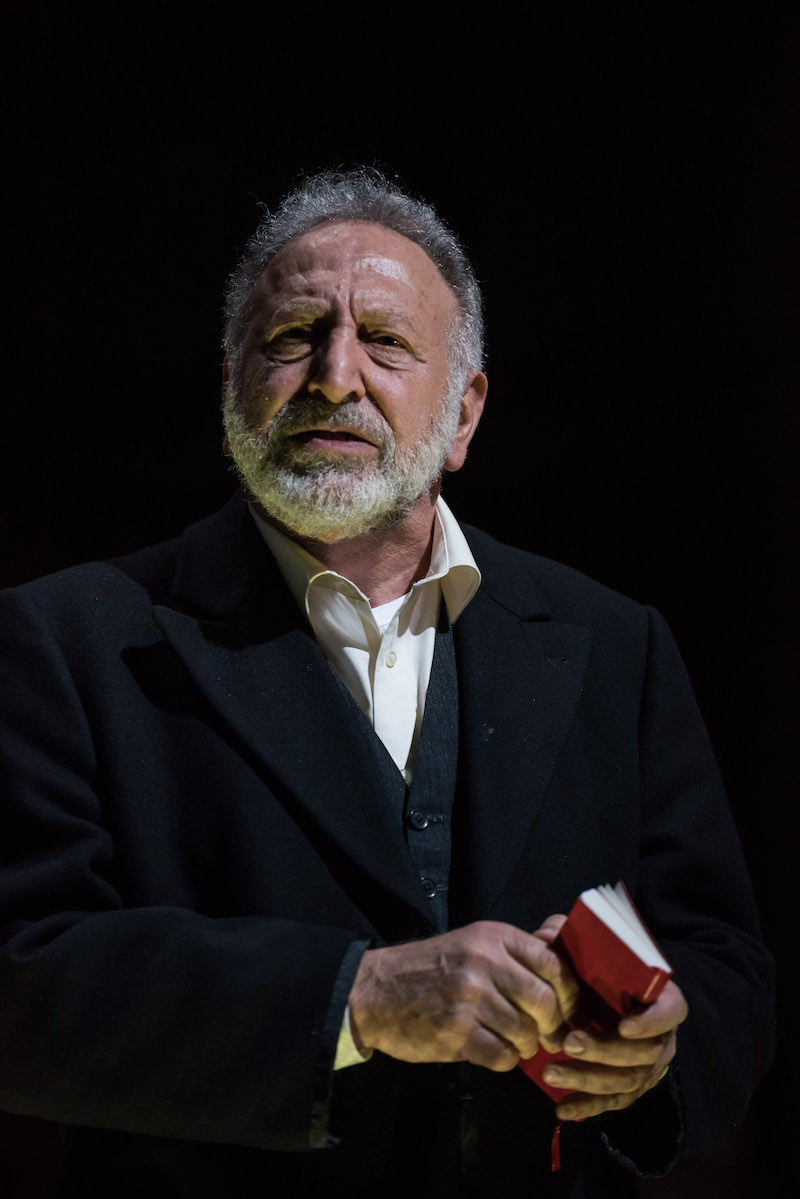

The character of Shylock (played here by Arab-Israeli actor Makram J Khoury, pictured left) and the gentile characters’ hostile reactions to his Jewishness have always sat uneasily in the Shakespearean pantheon. As has the play itself – it feels like a romcom welded to a courtroom drama. In Findlay’s hands, this Merchant becomes a parable on the limits of white liberal “tolerance”. The gentiles are happy to borrow money from Shylock, but God forbid he complain about the way they treat him – or claim what’s lawfully his.

The character of Shylock (played here by Arab-Israeli actor Makram J Khoury, pictured left) and the gentile characters’ hostile reactions to his Jewishness have always sat uneasily in the Shakespearean pantheon. As has the play itself – it feels like a romcom welded to a courtroom drama. In Findlay’s hands, this Merchant becomes a parable on the limits of white liberal “tolerance”. The gentiles are happy to borrow money from Shylock, but God forbid he complain about the way they treat him – or claim what’s lawfully his.

Findlay brings the text’s homoerotic elements to the fore from the get-go: the nature of the relationship between Antonio (Jamie Ballard) and Bassanio (the aptly-named Jacob Fortune-Lloyd) is made clear in the first five minutes. Ballard’s Antonio is spot-on – he is the first character we see, tearstained and hopeless, and his yearning for Bassanio is beautifully contrasted with his hatred of Shylock. This shift of focus towards Antonio could draw us away from the racial intolerance theme, but Findlay is more subtle than that. Khoury’s fiercely dignified presence lingers even when he’s not onstage, affecting what we see; once you’ve witnessed Antonio spitting into Shylock’s face, it’s difficult to sympathise with his unrequited love for Bassanio.

Despite this, the production can’t seem to quite make up its mind on how it wants to present racial prejudice. Some of the actors tend towards the cartoonishly villainous in their delivery of anti-Semitic lines, while Portia’s racist dismissal of the Moroccan prince is conveniently left out. This might be down to timing, but it still feels like a cop-out. Portia’s racism is anti-black, not just anti-Semitic, which marks her out from the other gentile characters. And yet she’s such a strong character, running rings around her dead father and new husband. Fortune-Lloyd’s Bassanio is a lovable idiot who needs an awful lot of comic nudging to pick the right casket.

Ferran navigates these nuances as skilfully as you’d expect from an Olivier winner (she won Best Actress for the Almeida’s Summer and Smoke last year). This woman was born to speak these lines, sometimes delivering them at startling speed that still leaves every word clear as day. Her scenes with Nadia Albina (pictured below, with Ferran), who plays her maidservant Nerissa, are a particular joy to watch, but Ferran is like a kind of acting catalyst: everybody gets better whenever she’s onstage.

Although it (sort of) ends with a wedding, this might be the least romantic of Shakespeare’s plays. Johannes Schütz’s shiny golden set reflects the characters back at them: in Venice, everything is filtered through cash-tinted glasses. Let’s face it, Bassanio wants to marry Portia because she’s rich. He gets the money for the trip to Belmont from Antonio, who gets it from Shylock, who gets it from Tubal (Gwilym Lloyd), another Jewish merchant. These latter three aren’t bound by friendly or familial relationships, but by mercantile interest. The play deals with this inconvenient truth by pinning all the greed and selfishness on Shylock, the convenient scapegoat. His demise is the only way to ensure a happy ending for Portia and Bassanio, but not for Antonio, whose tearstained face Findlay leaves us with. For somebody to win, somebody else has to lose – and the system was rigged from the start.

Although it (sort of) ends with a wedding, this might be the least romantic of Shakespeare’s plays. Johannes Schütz’s shiny golden set reflects the characters back at them: in Venice, everything is filtered through cash-tinted glasses. Let’s face it, Bassanio wants to marry Portia because she’s rich. He gets the money for the trip to Belmont from Antonio, who gets it from Shylock, who gets it from Tubal (Gwilym Lloyd), another Jewish merchant. These latter three aren’t bound by friendly or familial relationships, but by mercantile interest. The play deals with this inconvenient truth by pinning all the greed and selfishness on Shylock, the convenient scapegoat. His demise is the only way to ensure a happy ending for Portia and Bassanio, but not for Antonio, whose tearstained face Findlay leaves us with. For somebody to win, somebody else has to lose – and the system was rigged from the start.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Add comment