When the Canadian Yann Martel went to India as a young adult backpacker he fell in love – not with one person but with the rich imaginative landscape opened up by its religions and its animals. A struggling writer at the time, he channelled this new love into a dazzling idiosyncratic narrative about a shipwrecked Indian boy who survives 227 days at sea with a zebra, a hyena, an orangutan and a Bengal tiger called Richard Parker.

Millions of people have now been swept up in his Booker-winning magical realist odyssey. Director Ang Lee has captured it – not entirely successfully according to Martel – on film, while Max Webster’s Sheffield Crucible theatre production arrives in London on a flotilla of five-star reviews. The challenge for the production team for this transfer – which has been delayed, like so many, by Covid – has been to recreate the show so that we can feel the full roar of its impact from the proscenium arch of Wyndham’s.

Lolita Chakrabarti’s script – which plays up the book’s comedy over its gentle teasing philosophy – begins at the end of Martel’s narrative so that we witness Pi’s trials and tribulations in flashback. In contrast to the fantastical polychromatic world that is about to open up to us, we meet Pi hiding under a bed in a grey hospital room. Here he is being interrogated by two officials (in the book both male, here a man and a woman) about what happened when his ship, the Tsitsum, sank in the Pacific en route from India to Canada.

As the production unfolds there is much to love, but its astonishing power comes from the puppetry, which is overseen by Finn Caldwell who has a pedigree that goes back to the National Theatre’s War Horse. Together with Nick Barnes he has created animals that are believable in part because – not unlike artists of the late Renaissance – they are as interested in the muscle and sinew of what makes them work as in their external appearance.

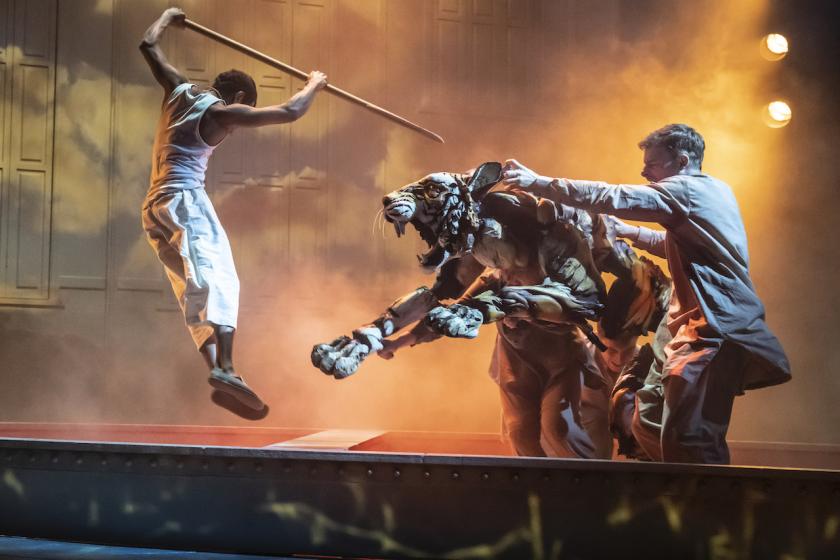

Take, for instance, Richard Parker the tiger (main picture). After watching hours of footage of tigers in the wild his creators became obsessed by the idea that cats – big and small – are anatomically like “stretchy accordions”. As a result every single one of the tiger’s joints are attached to its spine by bungee elastic. Like all the puppets, it is directly animated by the hands of its puppeteers so that each movement has both kinetic and emotional force; the overall impact is both potent and terrifying.

This is important because while the show’s overall tone is light, with a deceptive narrative simplicity that makes it perfect family viewing, what makes it resonate is the fact that at heart it’s a dark, terrifying story about the struggle to survive. These are not Disney animals but creatures who kill, and whether you see the story as spiritual metaphor or psychological escapism, it would have no substance without a sense of the danger they bring. Pi is played with charismatic vim and energy by Hiran Abeysekera (pictured above). No matter how ravishing the visual effects are swirling around him, he commands the audience’s attention with a muscular performance that convincingly shows the shift from witty innocent to someone who has witnessed more in months than some people do in an entire lifetime.

Pi is played with charismatic vim and energy by Hiran Abeysekera (pictured above). No matter how ravishing the visual effects are swirling around him, he commands the audience’s attention with a muscular performance that convincingly shows the shift from witty innocent to someone who has witnessed more in months than some people do in an entire lifetime.

The Wyndham's Theatre has been reconfigured for Tim Hatley’s clever, fluid design so that its ship-like structure can jut out into the stalls. At one moment, astonishingly, Abeysekera leaps onto what looks like solid ground, only to be swallowed up as if it were water. The striking similarity between the ropes and pulleys structure of a ship and a theatre is exploited to the full. The fact that the action takes place on several levels means that unusually, the best seats in the house are in the Grand Circle.

The effect is amplified by Tim Lutkin’s lighting, which allows us to feel the full impact both of the seascape and Pi’s colourful imagination. One of many visual highlights is the moment when he becomes aware of the ocean’s bioluminescence and is surrounded by stars and animated fish darting around him like streaks of light.

It's striking that Martel, like Neil Gaiman, has been inspired by both myths and religious texts to create an anti-rationalist narrative that taps into the emotions with a magical, otherworldly energy. Of the two shows now playing in the West End, I’d say that Gaiman’s Ocean at the End of the Lane packs a stronger emotional punch overall, but there are plenty of transcendent moments here and the reveal at the end is as sobering as it is jaw-dropping.

Other notable members of the cast include Mina Anwar as Pi’s mother and Tom Espiner (pictured above, far left) who does sterling work both as a puppeteer and as a whole range of characters including the wonderfully stiff-upper-lip Commander Grant-Jones. After lockdown has driven us all to different kinds of madness through living in confined spaces, Life of Pi’s very different take on isolation is a glorious fantastical escape. The tiger, on its own, will haunt your mind for a long time afterwards.

Add comment