I am fortunate to have worked as a director in theatre, film, television and radio, and so it was hugely intriguing to be invited to direct an online reading of Tom Stoppard’s beautiful 1964 play, A Separate Peace.

Here was a new form which could certainly borrow from existing forms, and I soon realised the question we should be asking was not, “What is an online reading?”, but “What could it be?”

Limitation, like desperation, can be the mother of invention. In the theatre, we can’t afford 20 actors, so we must figure out how to do the play with eight. In film, a location flooded last night so we have 30 minutes to relocate the scene from an office to a car park. Similarly, In this new setting, an online space, we began by taking a cold, hard look at the limitations, both technical and physical. In most story-telling mediums, a great deal of effort is spent hiding the nuts and bolts. We don’t want to see a boom mic hovering over Meryl Streep’s head, nor the costume change happening stage left at the Old Vic, unless that’s the point. The same applies to the novelty that is Zoom. How can we hide the nuts and bolts of this technology, and bring the actors and the story to the forefront? How can we enable the audience to lose themselves in their own lounge, as they might in a darkened cinema or theatre?

In most story-telling mediums, a great deal of effort is spent hiding the nuts and bolts. We don’t want to see a boom mic hovering over Meryl Streep’s head, nor the costume change happening stage left at the Old Vic, unless that’s the point. The same applies to the novelty that is Zoom. How can we hide the nuts and bolts of this technology, and bring the actors and the story to the forefront? How can we enable the audience to lose themselves in their own lounge, as they might in a darkened cinema or theatre?

On Zoom, there are two viewing options. Speaker mode shows only the person speaking on screen. Gallery mode shows all five actors. It presents five equally sized screens, five shots within one shot. As an audience member, it is only possible, just as in film and theatre, to focus on a single face at one time. Good.

Our five actors will be performing in their own homes. To me, it is quite deadly when attempting to transport an audience to see the details of a performer’s life displayed behind them. At the trashier end of curiosity, we are really interested in the wallpaper. Or the bookshelves.

So, the frame must be clean. We can help this story by finding a uniformed colour or tone to unite five actors who are in very different spaces: “a very specific nowhere,” as Beckett might say.

A Separate Peace is set in a private care home. A clean, white, “virtual background” seems to work, and so is uploaded with a degree of technical pain by our team, some requiring lengthy software updates, all of us needing to be taken through the process online with our stage manager and technical crew. Against this clinical brightness, we discovered that black clothing works most effectively.

Next, to achieve a superior and uniform level of sound and lighting, each actor is delivered a microphone, a ring light, and a paper copy of the script. There have been horror stories during this pandemic of online readings where electronic readers have crashed mid performance – a paper script can fall to the floor, but it can’t disappear.

Music and sound: with some wrangling, we are able to operate both of these much as we would in the theatre – live, according to cues in the prompt book. Our stage manager, Georgia Bird, will be in control of muting microphones when actors are not in scenes.

Entrances and exits are vitally important on stage, and no less so here. Because we can’t take away and add screens without exposing the technology, all cameras must be live throughout. Actors can walk in and out of frame (all our actors will be standing), but we also discovered how to make a "hard cut" into or out of a scene with a fold of paper over the camera. The simplicity of this low-fi solution is maybe my favourite discovery, and Denise Gough (pictured above top) in particular has found new and exciting ways of using it!

Entrances and exits are vitally important on stage, and no less so here. Because we can’t take away and add screens without exposing the technology, all cameras must be live throughout. Actors can walk in and out of frame (all our actors will be standing), but we also discovered how to make a "hard cut" into or out of a scene with a fold of paper over the camera. The simplicity of this low-fi solution is maybe my favourite discovery, and Denise Gough (pictured above top) in particular has found new and exciting ways of using it!

I described aspects of the production to Tom Stoppard over the phone:

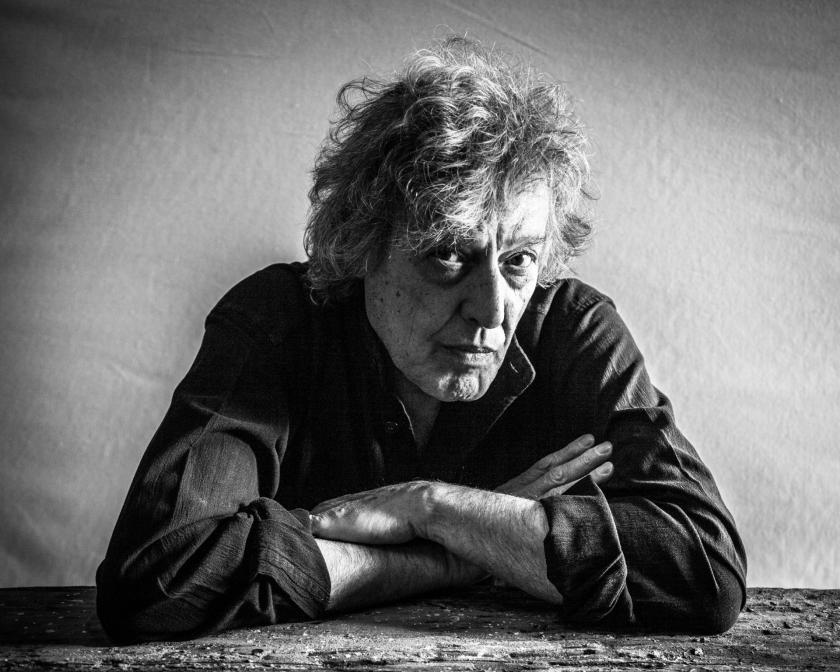

SY (pictured right) “There will be five actors in five white rectangles, on a black background...”

TS “Yes…”

SY “There will be some music, and some visuals…”

TS “And will it be pre-recorded?”

SY “No, it will be live.”

TS “Live? How wonderful!”

Tom’s boyish delight confirmed something: The most important element of this endeavour, as in the theatre, is knowing that the action in front of us is happening, and will only happen, now.

Art can be responsive to the very moment we live in. It is exciting to feel that we are pushing the current technological possibilities of this form to the max. New features will invariably follow, improvements to a form that may or may not continue once we are able to gather together again in person.

At this moment, though, it is a privilege for us to present Tom Stoppard’s play for audiences, and in doing so, to give financial support to technicians in our industry, and to The Felix Project, a wonderful charity who rescue good food that might otherwise go to waste and deliver it to those in need.

In A Separate Peace, Denise Gough’s character says to David Morrissey’s: “It’s not enough, Mr Brown. You’ve got to… connect…”

Let’s try.

Add comment