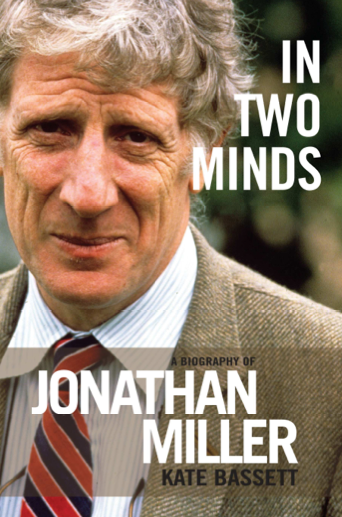

When I first mentioned to a colleague that I was embarking on a biography of the doctor/director Jonathan Miller, he instantly yelped, “My God, your work’s cut out! The man must have met half the famous names in the twentieth century!"

My subsequent conversations with Miller provided a cornucopia of highly entertaining anecdotes. These included his brushes with Princess Margaret (who was very taken with his comic turns in the 1950s); Bobby Kennedy (who told him to shut up, shortly before being shot); Bridget Riley (who nearly sued); and Kevin Spacey (who got his big break by stalking Miller for an audition).

Equally delightful, for me, have been Miller’s erudition, eloquence, and polymathic range. In his restlessly prolific career, he has not just switched from the operating theatre to opera and theatre, via the satiric hit revue Beyond the Fringe. He has run the Old Vic (1988-90), and been a chatshow favourite and a top TV presenter and producer – notably of the BBC’S 13-part history of medicine The Body in Question and the Corporation’s mammoth Shakespeare Series. More recently, he has curated for the National Gallery, and become an exhibited collagist and sculptor.

Though known for his insult-slinging bust-ups, not least with Sir Peter Hall, he has mainly been a brilliant connector, straddling the arts and the sciences. Yet he has felt endlessly torn, guilt-ridden that he didn’t concentrate on neuropsychology.

In researching this biography, I further learned of his complicated ancestry – his grandparents being illiterate Lithuanian immigrants who fled anti-Semitism – and of how the crucial arts-science dichotomy was rooted in his parents' marriage. His mother, Betty, was a Bloomsbury novelist while his father, Emanuel, a leading child psychiatrist, failed to prize his son’s life in the theatre.

The extract overleaf focuses in on 1969-70, when the elderly Emanuel was near death’s door, and Miller triumphed at the National Theatre, working with Laurence Olivier.

By 1969, the celebrated theatre reviewer Ken Tynan had been recruited from the critics’ ranks to join the National Theatre team, which was resident at London’s Old Vic, so he was working as Olivier’s literary adviser and right-hand man. As soon as he had seen Miller’s production of Lear in Nottingham – judged by the pundit Martin Esslin to be the play’s most lucid rendition in living memory – Tynan proposed Miller as the perfect director for The Merchant of Venice, because Sir Laurence’s wife, Joan Plowright, was wanting to play Portia.

Her husband might well have dismissed Tynan’s idea, for he had been unamused by Beyond the Fringe’s spoof of enervating Old Vic productions of Shakespeare in 1960. Worse still, Miller’s unflattering comments about Olivier’s blacked-up Othello, casually confided in a journalist, had appeared in print.

Consequently, when the phone rang and the caller at the other end of the line claimed to be the great man, Miller assumed it was a joke. As he explains: "I heard this voice saying, 'Dear boy, I would like you to do The Merchant of Venice for Joanie', and I thought it was Alan Bennett or Peter Cook [from Beyond the Fringe] pulling my leg. Well, he grew rather impatient and said, 'No, no, it is Laurence Olivier!'... I managed to say, 'I’d love to do it'."

Olivier recognised that this young director had given him a new lease of life, reinvigorating his reputation as a great Shakespearean actor

Soon the veteran star announced that he was going to join Plowright, taking the part of Shylock. This scotched the rumour that he was retiring after his battle with cancer, and he turned up at the first read-through already word-perfect. Unfortunately, he came bearing a bag of facial appendages that appalled Miller: the stock-in-trade hooked nose, orthodox ringlets, and a costly set of jutting teeth which were apparently based on a Jewish member of the NT board. The duo, as a result, got off to a sticky start, but Miller managed to wean Olivier off his worst accessories, with the actor enthusiastically concurring: "In this play, dear boy, we must at all costs avoid offending the Hebrews. God, I love them so!" He was allowed to keep the teeth, which were not especially Jewish in any case. Sir Laurence loved his dentures so, he used to wander around the corridors and give press interviews with them in, to see if people noticed.

He was very taken with the idea of an 1890s Shylock who would appear assimilated at first glance, and who could have a hint of Disraeli or of the emergent Rothschild dynasty about him. In his dapperness, this Shylock was also like Miller’s own grandfather, the émigré turned smart-suited merchant and bank man, Simon Spiro. Thus, the director’s ancestral backstory of complex assimilation fed into this staging. The production essentially made Shylock and his child, Jessica, "Jew-ish" in different and conflicting ways. Olivier’s Shylock was a clean-shaven man, with a morning coat, wing collar and attaché case, barely distinguishable from Antonio’s fraternity of mercenary Christian gentlemen. At the same time he was, as one critic noted, a divided self. He was seen donning a prayer shawl at home, not so far from Spiro and Emanuel Miller on the Sabbath – rituals which Jonathan had rejected, causing a rift. In turn, Shylock’s daughter, Jessica, as played by Jane Lapotaire, had shown signs of an anti-father complex and rejected her father’s world. Presumably Miller thought Emanuel would draw his own parallels. In a letter to his old school friend Oliver Sacks, he exclaimed: "Thank God my father is too lame to get into the theatre!"

He was very taken with the idea of an 1890s Shylock who would appear assimilated at first glance, and who could have a hint of Disraeli or of the emergent Rothschild dynasty about him. In his dapperness, this Shylock was also like Miller’s own grandfather, the émigré turned smart-suited merchant and bank man, Simon Spiro. Thus, the director’s ancestral backstory of complex assimilation fed into this staging. The production essentially made Shylock and his child, Jessica, "Jew-ish" in different and conflicting ways. Olivier’s Shylock was a clean-shaven man, with a morning coat, wing collar and attaché case, barely distinguishable from Antonio’s fraternity of mercenary Christian gentlemen. At the same time he was, as one critic noted, a divided self. He was seen donning a prayer shawl at home, not so far from Spiro and Emanuel Miller on the Sabbath – rituals which Jonathan had rejected, causing a rift. In turn, Shylock’s daughter, Jessica, as played by Jane Lapotaire, had shown signs of an anti-father complex and rejected her father’s world. Presumably Miller thought Emanuel would draw his own parallels. In a letter to his old school friend Oliver Sacks, he exclaimed: "Thank God my father is too lame to get into the theatre!"

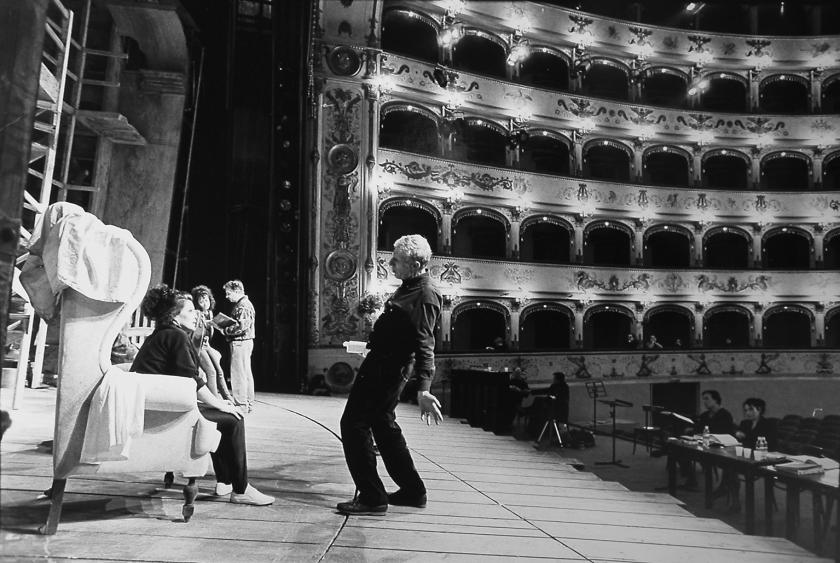

The general public flocked to see the production and, having been tentatively scheduled for just seven performances, it was soon being debated keenly and called the most important theatrical event of the year. Besides transferring for an extended run to the NT’s newly-acquired, second auditorium in the West End, the Cambridge Theatre, The Merchant was filmed, broadcast on television (pictured above right) and sold in the new format of video.

Olivier was delighted. He adored the electrifying bits of stage business which his director had suggested, not least the gleeful jig into which Shylock launched on hearing of Antonio’s wrecked fleet. That was loosely based on Hitler’s stomp of triumph at France’s defeat, recorded on a wartime newsreel. Olivier wrote, a decade later: "Jonathan excited us beyond measure by the limitless variety, the originality, and the fascinating colour in the expression of his ideas. He was the only man; we were thrilled by him and remain so." The Merchant had also helped Sir Laurence recover from five years of crippling stage fright. There were hairy moments during the initial performances as the sweat-drenched luminary downed tranquillizers to stop himself leaping on the first bus home. He begged his fellow actors not to look directly at him and, on one occasion, he almost forgot what a Jew hath. Miller recalls standing in the wings and glimpsing his terrified eyes staring out as if from behind a mask.

Having got through that, Olivier recognised that this young director had given him a new lease of life, reinvigorating his reputation as a great Shakespearean actor by daring to show the king of British theatre some healthy disrespect. This was a complex kind of paternal-filial relationship. Sir Laurence noted that the ticking-off [about his theatrical mannerisms] made him feel like the junior player or an embarrassed schoolboy, while Miller has inversely remarked: "He was a father to the company in every sense of the word – positive and negative. In the years I worked for the National, I had all those complicated, equivocal feelings that sons have for their fathers." He goes on to say:

Having got through that, Olivier recognised that this young director had given him a new lease of life, reinvigorating his reputation as a great Shakespearean actor by daring to show the king of British theatre some healthy disrespect. This was a complex kind of paternal-filial relationship. Sir Laurence noted that the ticking-off [about his theatrical mannerisms] made him feel like the junior player or an embarrassed schoolboy, while Miller has inversely remarked: "He was a father to the company in every sense of the word – positive and negative. In the years I worked for the National, I had all those complicated, equivocal feelings that sons have for their fathers." He goes on to say:

"He had a paternal intimacy with everyone, drifting into the canteen with his saucer over his coffee-cup to keep it warm, sitting down for a chat. He didn’t lock himself away. I tell you what it was like: it was like a small bomber command squadron in those Nissen huts [the company’s makeshift offices] at the back of Aquinas Street. The chaps were ready to scramble for this ’ere Flight Commander. Olivier had this sort of patrician hospitality and a real interest in all his staff’s welfare which, in turn, generated enormous filial affection and admiration."

Though very convivial by comparison [with Miller’s notorious feud with the next boss of the NT, Peter Hall], the course of Miller and Olivier’s relationship had not run altogether smoothly. Sir Laurence and Tynan had considered Miller’s NT staging of Danton’s Death to have been so disastrously arid that they denied him The Bacchae. Moreover, Plowright had been horrified when she saw that the final proofs of Logan Gourlay’s book Olivier included a Miller interview which mixed warm praise with comment on the great man’s stubborn ego. The culprit ended up frantically handing over £700 to censor himself, paying for a reprint with his contribution excised. One colleague recalls him saying he ought to kill himself, and Miller confirms:

"I was extremely upset that I’d allowed myself to speak unkindly. I owed everything to him really, and he was always kind and decent and supportive to me. I would have done anything to have it taken out because I think it was ungracious and ungrateful – in a way I don’t feel about whatever I’ve said regarding Peter Hall, because he was never kind."

- Oberon Books are offering readers of theartsdesk a 20 percent discount on In Two Minds: a Biography of Jonathan Miller. Visit the Oberon website and enter ONMILLER at the checkout

Add comment