Can a play peak too soon? That's the quandary that attends the Old Vic airing of Eureka Day, Jonathan Spector's on-point if overextended comedy that was written prior to the pandemic but has absolutely come into its own just now. A skewering of liberal pieties that puts one in mind of a fellow theatrical satirist like Bruce Norris (Clybourne Park), Eureka Day takes few prisoners on the way to a flat-seeming ending.

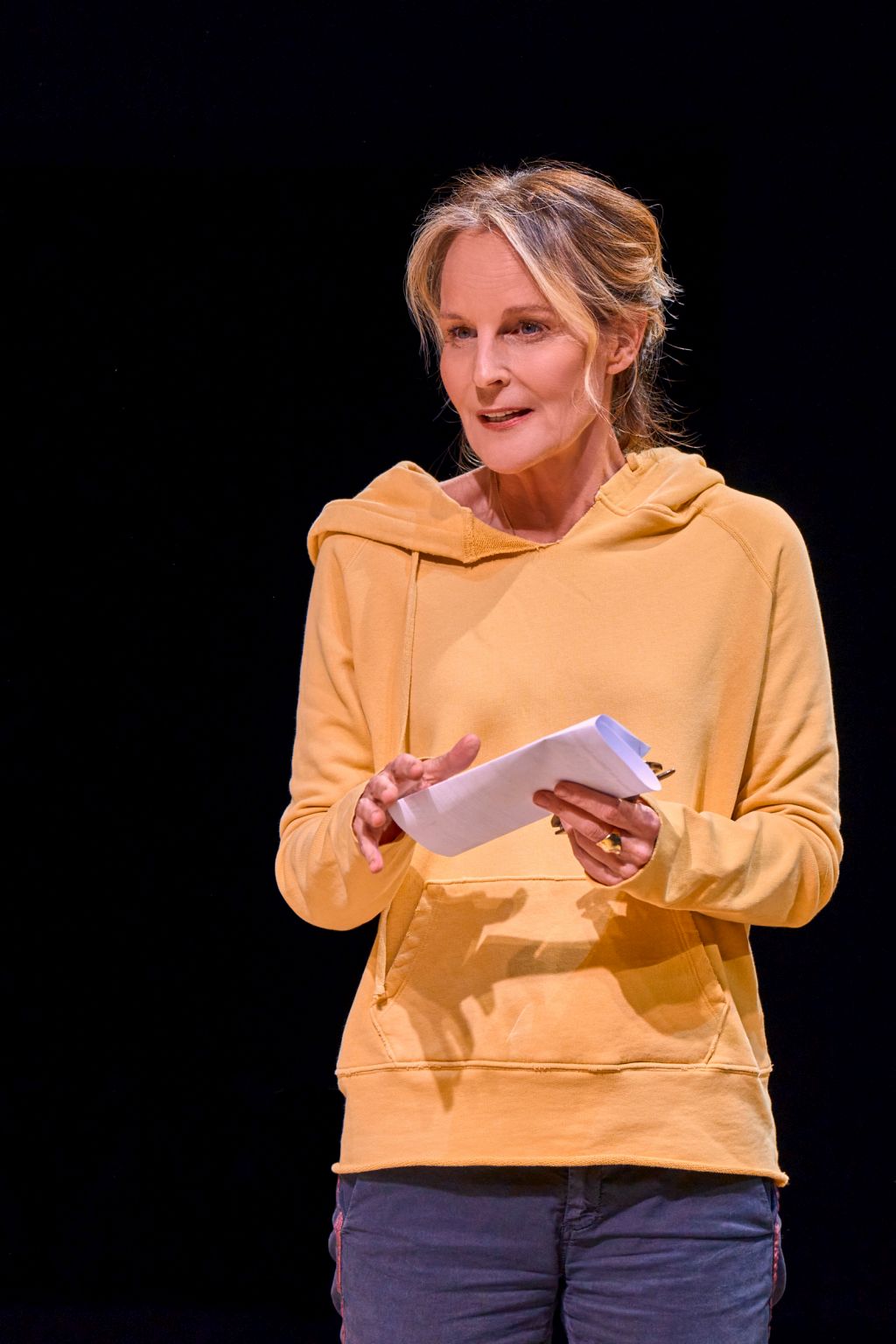

But Katy Rudd's production, featuring Helen Hunt (pictured below) in a notably unstarry London stage debut, is lucky enough before that to have sent the audience into the interval abuzz from the single best-realised scene I've encountered in many a month. Spector's 2018 play, premiered in Berkeley, California, where it is set before an Off Broadway run and now London, posits an online gathering that devolves quickly and ineluctably from civility into cacophony.

The slide into chaos amongst this amalgam of academics and parents exists in accordance with an ever more-divisive and polarised culture in which the perpetual thumbs ups proffered by one cheerful-seeming respondent come to seem like straws in the wind. The specific sticking point may be the MMR vaccine – nowadays it would be Covid – but what's really at stake is the very possibility of consensus. "Nobody in this room is a villain," or so the play's de facto mediator Don (a winning Mark McKinney) may assert, but the play leaves no doubt that society itself is the loser when fractiousness becomes the inevitable destination, whatever the debate.

The slide into chaos amongst this amalgam of academics and parents exists in accordance with an ever more-divisive and polarised culture in which the perpetual thumbs ups proffered by one cheerful-seeming respondent come to seem like straws in the wind. The specific sticking point may be the MMR vaccine – nowadays it would be Covid – but what's really at stake is the very possibility of consensus. "Nobody in this room is a villain," or so the play's de facto mediator Don (a winning Mark McKinney) may assert, but the play leaves no doubt that society itself is the loser when fractiousness becomes the inevitable destination, whatever the debate.

Had Bruce Norris been at the helm, one can imagine this same material drawing blood. As it is, the writing elicits those belly laughs mentioned late in act one, followed by a more earnest and prosaic second half that deepens the characters so that they occupy more than just positions on the spectrum of opinion. And such is the breadth of Spector's targets that spectators are likely to see themselves somewhere on view: it's been interesting in early responses to the play that the right-wing press has been the most favourable, which is an irony worthy of the play itself.

Rob Howell's cheerful set – its image of so many little linked hands another irony – delivers the school of the title, where gender-neutral pronouns are the preferred currency and organic doughnuts the grub of choice. "Our diversity is the source of our strength," opines the shambolic-seeming Don, an ageing hippy who is a visual sight gag in himself well before the laptop scene prompts peals of laughter that render onstage conversation irrelevant: you can't hear it over the audience's gathering euphorium. (I love the way, too, that these adults often look too big for the furniture allotted them, as suits a regression into recrimination worthy of the most unruly of playgrounds: the cast is pictured below.)

All the hot button topics get a look-in, from evolution and creationism posited by Carina (Susan Kelechi Watson, from TV's This Is Us) to the devastating dependency on opiods voiced by Hunt's Suzanne, whose calm isn't quite as total as it might seem at first. All points of view may be valid, but are they being heard, or understood? That's the question besetting a community for whom The New Yorker may be gospel but who can't even find consensus in the room, which doesn't bode well for the hoped-for herd immunity Carina introduces into the mix. Rudd, the director, furthers here an interest in the American canon that made her Camp Siegfried at this same address so revelatory, and Spector's play doesn't ignite to the degree that one did. But it's nice to see Ben Schnetzer, from Matthew Warchus's terrific film Pride, now appearing at the very theatre that Warchus runs, and one only wishes his part as a philandering, stay-at-home dad wasn't sidelined in the more-sententious second act. Kirsten Foster is good, too, as the fragile May who knits ever more aggressively as her emotions take her over.

Rudd, the director, furthers here an interest in the American canon that made her Camp Siegfried at this same address so revelatory, and Spector's play doesn't ignite to the degree that one did. But it's nice to see Ben Schnetzer, from Matthew Warchus's terrific film Pride, now appearing at the very theatre that Warchus runs, and one only wishes his part as a philandering, stay-at-home dad wasn't sidelined in the more-sententious second act. Kirsten Foster is good, too, as the fragile May who knits ever more aggressively as her emotions take her over.

If the net result doesn't fully land, that's due more to a set-up that doesn't find a corresponding pay-off: Spector may be too essentially genial to go in for the kill that you keep thinking lies in wait. But as an equivalent of sorts to the Yasmina Reza of old who gave us God of Carnage (a stage hit for Matthew Warchus, as it happens), this is very much a play for today that at its best unites playgoers in laughter even when the world at large disunifies us increasingly at every turn.

Add comment