As hurricanes rip into the American Gulf states with increasing ferocity, Eastern Europe disappears underwater and even the gentle British rain becomes a deluge, the arrival of Daisy Hall’s debut play Bellringers at Hampstead Theatre’s Downstairs space couldn’t be more timely,

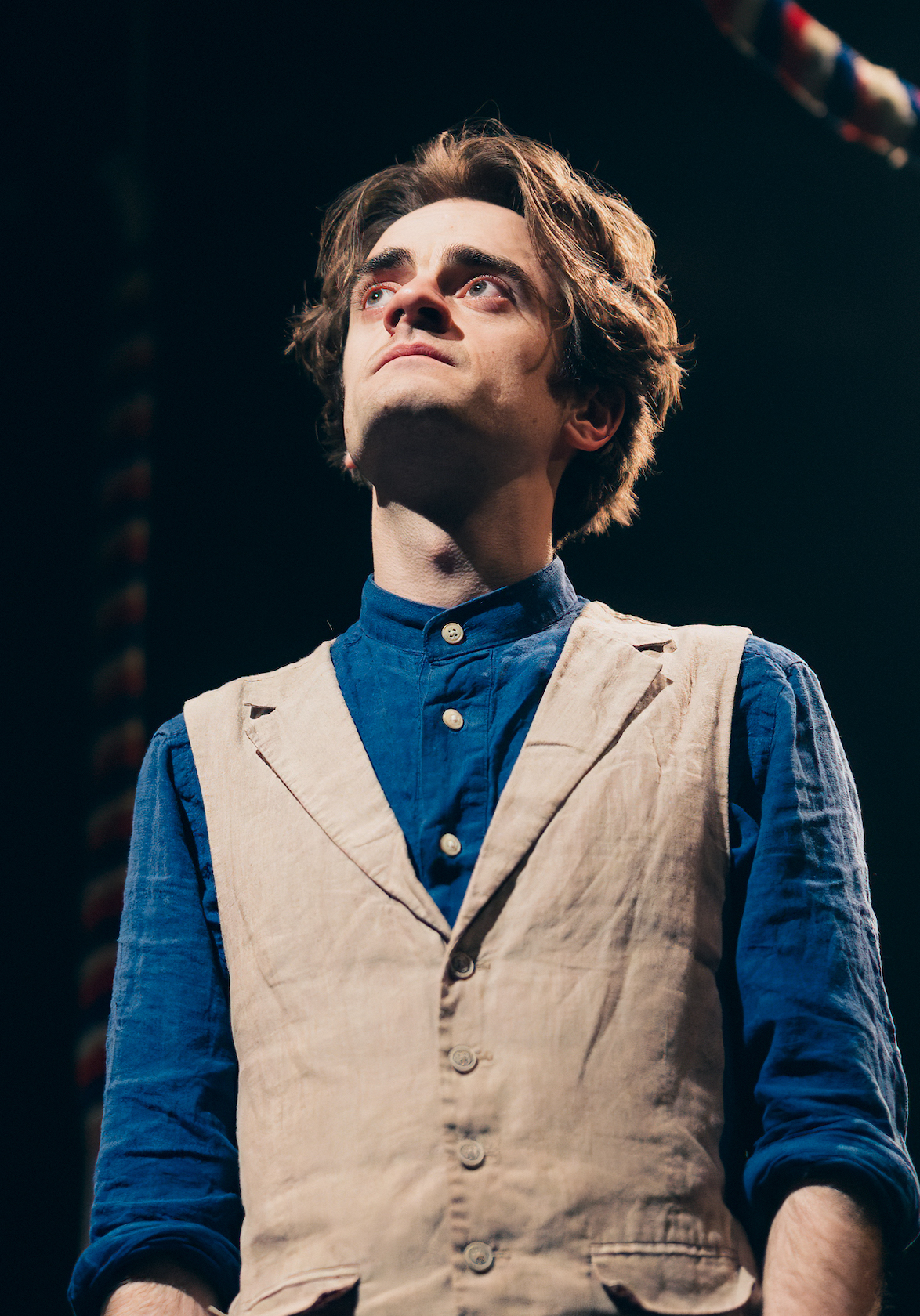

The scene throughout is a belfry, with bell-ringing ropes hanging overhead, where two men in monks’ habits have just arrived. Outside, rain is beating down. The two men, Aspinall (Paul Adeyefa) and Clement (Luke Rollason, pictured below), begin to argue about when they should ring the bells, whether they actually need to be rung, whether they make a difference as the flood waters rise.

Yes, this is a play about climate change, but that description shortchanges it. In a spare 75 minutes, Hall packs in wide-roving, funny discussions about belief vs superstition, atheism vs blind faith, community welfare vs individual survival, and creates a whole universe of dampness, where mushrooms sprout up everywhere, fish fall from the skies and the rain it raineth every day. When Clement is prevailed upon by the more orthodox Aspinall to deliver a sermon, he envisages the incarnation of Jesus at different stages, as a fish, a mushroom, a woodlouse.

A play about Aspinall’s mother’s favourite doomy subject, the end of the world, could be either hectoring or whimsical or ludicrously sci-fi, but this one is none of those. Its secret weapon is a playful form of absurdist humour; it’s dark but grounded in a version of real life, with relatable ethical quandaries and a specific and recognisable geography.

As the two men start discussing local goings-on and fatalities – “frazzling” is a common fate (being felled by a lightning strike, as the men may be when they start ringing the bells), along with drowning or being burnt in a fire during a drought, presumably – the terrain becomes clear. We are in the Cotswolds villages around Chipping Norton, with Chadlington mentioned regularly (fans of Jeremy Clarkson will know this is his manor; it’s also the area where Hall grew up).

The importance of bell-ringing starts to emerge. Roscoe over in Chadlington has created a peal that is said to be able to see off the thunderstorms, breaking up the clouds and sparing the humans below. Clem has a more scientific explanation for a storm dying. It runs out “of water, or lightning, or something”. But for Aspinall’s sake he goes along with the notion that a special peal might help.

Much of the play’s depth stems from the rapport between the two men, and Rollason and Adeyefa couldn’t be a better mix. Adeyefa has the solidity of an optimist, always expecting the sun to come out and lambs to be born with just one head again. He loves his mate Clem and follows his lead, though not into nihilism. Rollason’s Clem is an extraordinary turn: a skinny pipe cleaner of a man, with huge doleful eyes and a thick thatch of hair, he takes lines with no obvious humorous potential and makes comic gold of them. When he tries the simple act of lighting a soggy spliff that falls onto his chin like a dead worm, you can see the value of his Philippe Gaulier physical comedy training. But Clem is also oddly heroic, wanting to support his best friend by pretending things could improve and that prayer – not to mention creative bell-ringing – is worth a try. He’s also prepared to sacrifice himself for Aspinall. I haven’t seen such a striking performance in a long time.

Much of the play’s depth stems from the rapport between the two men, and Rollason and Adeyefa couldn’t be a better mix. Adeyefa has the solidity of an optimist, always expecting the sun to come out and lambs to be born with just one head again. He loves his mate Clem and follows his lead, though not into nihilism. Rollason’s Clem is an extraordinary turn: a skinny pipe cleaner of a man, with huge doleful eyes and a thick thatch of hair, he takes lines with no obvious humorous potential and makes comic gold of them. When he tries the simple act of lighting a soggy spliff that falls onto his chin like a dead worm, you can see the value of his Philippe Gaulier physical comedy training. But Clem is also oddly heroic, wanting to support his best friend by pretending things could improve and that prayer – not to mention creative bell-ringing – is worth a try. He’s also prepared to sacrifice himself for Aspinall. I haven’t seen such a striking performance in a long time.

The wealth of references feeding into this piece is surprising. Hall says she had not set out to write plays but abandoned a career as a novelist after falling in with a theatrical crowd when she wrote a radio play during lockdown, who spurred her to read every playtext she could find. Her influences aren’t hard to spot – Pinter, Lucy Kirkwood (especially The Children), Jez Butterworth and above all Beckett. What she has written is a sort of Waiting for Godot for the Cornetto Trilogy generation, where the familiar has become nightnarish, with a touch of the poignancy of Journey’s End as well. It is also a play steeped in the horrors and privations of Covid, a smothering force like the burgeoning fungi in the Cotswolds.

That’s not to say the play is derivative. It breathes an atmosphere that’s confidently all its own, expertly directed by Jessica Lazar, who keeps the lightning and thunderclaps coming (the excellent sound design is by Holly Kahn, the lighting by David Doyle) and the tone shifting effortlessly as the men edge towards possible oblivion. More from all concerned, please!

Add comment