Antonio Pappano, artistic director and chief conductor of the Royal Opera House, is a polymath, for he is also a brilliant and persuasive narrator of the history of music. Here he embarked on a four part history of the operatic voice, starting at the very top – or how to reach those high Cs, the Everest for the soprano.

Often speaking beside a grand piano, on the grand and empty stage of the ROH, and thus subliminally reminding us that he first worked as a repetiteur before becoming one of the world’s leading conductors, he creatively interweaved vintage film of legendary performances and interviews of the soprano greats of the 20th century with his own conversations with sopranos now. Warming to his subject, Pappano explained that he started with the soprano as it is perhaps the most flexible range of all, lyrical, poetic, gutsy, dramatic. Yet the church because of St Paul banned women from singing in church, and the first soprano musical lines were of course sung by boys. But by the 16th century renaissance courts began to welcome professional women singers, and then came opera (Maria Callas, pictured below).

In opera the soprano is conventionally long-suffering, usually dying, and plays roles ranging from fearsome warriors and feisty servant girls to murderous divas and scheming wives. And so to Verdi's Lady Macbeth, played by Anna Netrebko, who prepares by listening to 20 recorded versions of the role by other sopranos, taking and discarding as she absorbs what is possible, in order reach her own interpretation.

In opera the soprano is conventionally long-suffering, usually dying, and plays roles ranging from fearsome warriors and feisty servant girls to murderous divas and scheming wives. And so to Verdi's Lady Macbeth, played by Anna Netrebko, who prepares by listening to 20 recorded versions of the role by other sopranos, taking and discarding as she absorbs what is possible, in order reach her own interpretation.

Pappano reminds us that all seven billion people in the world possess one unique musical instrument, our voice, so how does it all work? The young soprano Anna Siminski sang the Queen of the Night from Mozart’s Magic Flute – high Cs and even Fs galore – from inside an MRI scanner so a consultant neurologist could show us the actual physical process of singing. Evidently the larynx, small as it is, has more muscles than any single organ, some 20 in all. The voice comes from the chest – and the head.

Pappano paraded the extraordinary variety of mid-20th prima donnas – Birgit Nilsson, Wagnerian extraordinaire, yet adept at the most astonishing ornamentation in Puccini’s Turandot, was a farmer’s daughter from Sweden, and milked 10 cows on the day she also went off to audition for a place at the Swedish Royal Academy of Music. Leontyne Price was nurtured by her Methodist church and the support of her family in her segregated home town of Laurel, Mississippi; her leading role was that of the enslaved African princess in Verdi’s Aida.

Renée Fleming revealed that as a student all she could think of was how to channel Leontyne Price’s miraculous high Cs. Joan Sutherland was a six-foot-tall Australian whose ambition was to sing at the ROH, although when she arrived in London after her six week voyage to England she failed her ROH auditions twice. Her nickname was La Stupenda, and she remarked that she did not know whether that applied to her size or her voice.

And we saw the most astonishing phenomenon of all: filmed excerpts of Maria Callas as Tosca acting her heart out, trying to be quietly austere when being badgered by journalists, and simply saying that the way any artist should sing was simply to listen to the music, with your ears and your soul. One cannot help but wonder what she would think of some of the current excesses of directors’ opera today. She was also evidently not only an anxious personality off stage but an incredibly nervous performer. Sir John Tooley, a past chief executive of the ROH, remembered that his arm was black and blue after escorting Callas, she had clutched him so tightly.

And we saw the most astonishing phenomenon of all: filmed excerpts of Maria Callas as Tosca acting her heart out, trying to be quietly austere when being badgered by journalists, and simply saying that the way any artist should sing was simply to listen to the music, with your ears and your soul. One cannot help but wonder what she would think of some of the current excesses of directors’ opera today. She was also evidently not only an anxious personality off stage but an incredibly nervous performer. Sir John Tooley, a past chief executive of the ROH, remembered that his arm was black and blue after escorting Callas, she had clutched him so tightly.

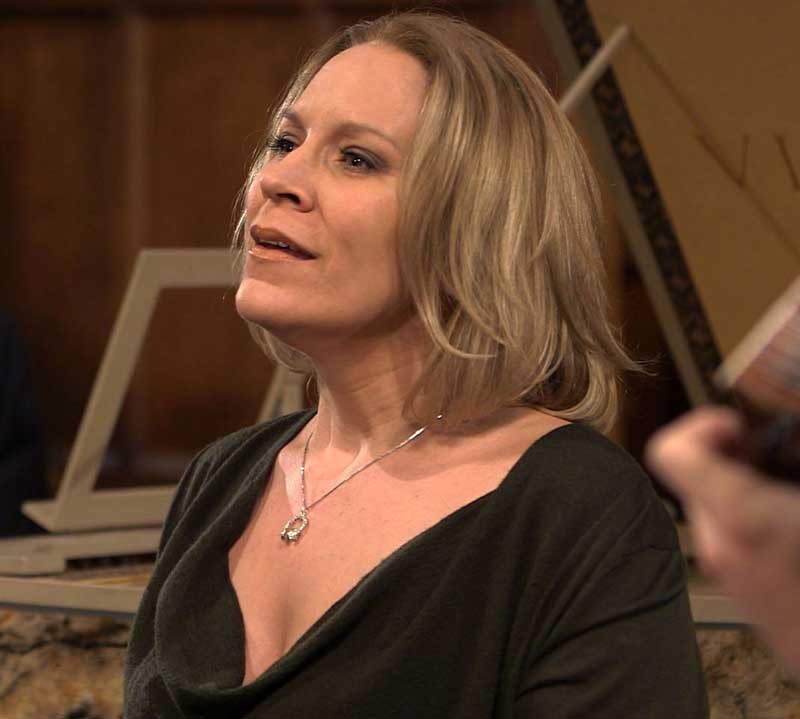

Back with the living, Pappano delved into the differences between vibrato and non-vibrato in Carolyn Sampson’s lament, Dowland’s "In Darkness Let me Dwell", not to mention her wickedly narcissistic turn as Handel’s Semele in the aria "Myself I shall adore" (Carolyn Sampson pictured above).

The Dutch soprano Eva-Maria Westbroek told us of the role of her life, as Anna Nicole in Mark Anthony Turnage’s eponymous opera, a true story of classic operatic ingredients: a rise from nothing to wealth, a fall from grace, overwhelming loss and early death. And Pappano, with elegant impatience, has no truck with those who think opera elitist. Opera, he showed us, does what it has always done, laying bare the prejudices, assumptions and hypocrisies of the world around us.

Add comment