Blu-ray: Ingmar Bergman Vol 4 | reviews, news & interviews

Blu-ray: Ingmar Bergman Vol 4

Blu-ray: Ingmar Bergman Vol 4

The Swedish master-magician of the cinema's late mid-life movies

Another box-set from the BFI full of Bergman treasures, from core catalogue classics such as Fanny and Alexander (1982), Cries and Whispers (1972), Autumn Sonata (1978) and Scenes from a Marriage (1973) to less well-known films such as After the Rehearsal (1984) and From the Lives of Marionettes (1980).

There are no comedies here – late mid-life brought out the full darkness of the Swedish director’s palette – although Fanny and Alexander both delights and shocks as it combines a characteristic lightness of touch, including a much-loved farting uncle and a child’s eye view of adult rituals, with the terrifying sadism of a Protestant step-father from hell. Could this be Bergman’s magnum opus? It is often referred to in those terms, and yet the writer and director’s work is distinguished above all by a great diversity underpinned by a singular vision of the human condition. Essential Bergman isn't to be be found in a single film: it is spread out, in all its rich variety across all of the BFI box-sets. In this case, we are offered the TV series version of Fanny and Alexander as well as the full theatrical release.

The French term auteur has been colonised by film critics, not least the men from the Cahiers du Cinéma, but it basically just means "author", without any of the pretension that inevitably came with "auteur theory". What makes Bergman, who wrote the scripts for all his mature films, so interesting and unique is that he is often drawing on personal experience, even when the stories are set in the past. We never lose sight that he is a man of the theatre – a universe whose wonders captured his imagination as a child.

After the Rehearsal (1984) is a marvellous vehicle for Erland Josephson, a versatile actor who features as much in these later films as Gunnar Björnstrand and Max von Sydow did in the early years. The men in Bergman films are generally either weak or else tyrannical, the bullying often covering up for a lack of inner strength. Josephson incarnates a more complex figure – perhaps closer to Bergman in his mature years. In this clever and bewitching exploration of fact and fiction, illusion and reality, all in the context of a real theatre in which all the action unfolds, as well as the world of "theatre" as a form of magic, Josephson is at his very best, evoking very powerfully the essence of Bergman himself.

There is indeed always something very theatrical in the master’s films, whether played out within the confines of a house, a hotel or the bleak landscape and coast of the island of Fårö. It is as if the setting of the drama in some way acts as a fulcrum for the interpersonal or inner story that unfolds.

There is indeed always something very theatrical in the master’s films, whether played out within the confines of a house, a hotel or the bleak landscape and coast of the island of Fårö. It is as if the setting of the drama in some way acts as a fulcrum for the interpersonal or inner story that unfolds.

The houses in Fanny and Alexander (1982) are a case in point – the lush and comforting ambiance of the family home where the film begins contrasted with the bleak and puritanical barrenness of the tyrannical bishop’s abode, hardly a home at all, but a place of permanent penance.

Guilt, desire, the ever-present challenge of love, an absconding God and the terror that comes with a sense of spiritual or personal abandonment – all of these run through Bergman’s work in various ways: he never does anything less than explore with relentless depth the great existential and spiritual questions. He works, alone with Tarkovsky, an essential vein barely touched by other cinematic traditions.

From the Lives of the Marionettes (1980) is an odd film – made in Germany (for tax reasons) without Bergman’s usual actors, but with outstanding camerawork from Sven Nykvist. Very formal, in a manner reminiscent of Persona (1966), with plenty of lingering close-ups and some extraordinary dream sequences, the film presents a series of dialogues around a man’s murder, at the start of the film, of a prostitute. This is one of Bergman’s more experimental movies, not fully realised but fascinating all the same, a reflection of the man’s ceaselessly searching nature.

In Autumn Sonata (1978), Ingrid Bergman (no relation!) stars in her final role as a concert pianist in her waning years who visits her estranged daughter; the director revisits the perennial inadequacy and torment of parent-child relations and the existential challenge that comes from being cursed or blessed by the presence of illness or handicap.

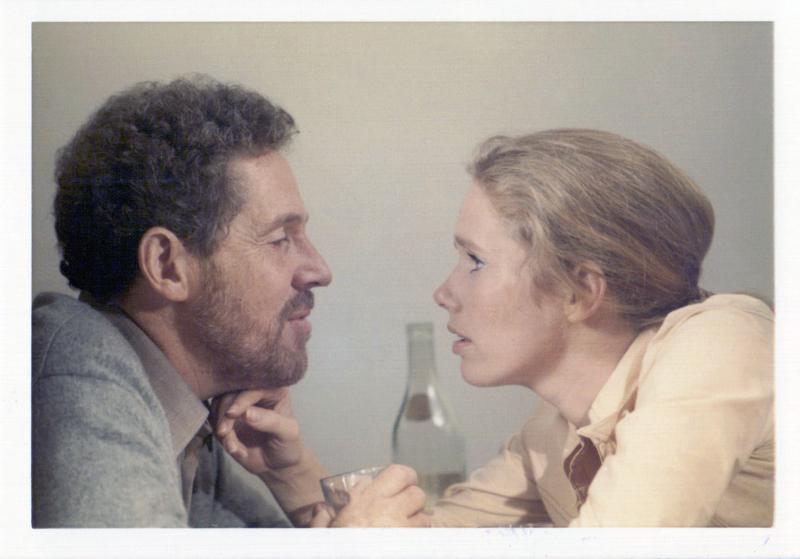

Scenes from a Marriage (1973) – which I remember first watching with a gut-wrenching sense of shared pain as my own marriage was unravelling – is the most forensic account of a couple both irrevocably bound together and incapable of sharing their lives, once again carried by extraordinary acting from Erland Josephson and Liv Ullman. They both return in Cries and Whispers (1972) (pictured above), which is probably the most powerful, heart-wrenching and perfectly accomplished film in this latest collection. Three sisters are cooped up in a country mansion, that unity of place again giving Bergman’s film such strength. One of them, played by the sublime Harriet Andersson, is dying. The other two manifest different aspects of womanhood, subjects that Bergman devoted himself to with unparalleled empathy: Maria (Liv Ullman), flirtatious, over-sensitive, contrasted with the more reserved Karin (Ingrid Thulin). The servant, Agnes (Kari Sylwan), incarnates a kind of positive mother figure. It is not the first time in Bergman’s films – I am thinking, for instance, of Bibi Andersson in The Seventh Seal (1957) – that innocence and a capacity for love are more likely incarnated in someone from outside the uptight bourgeois world on which he mostly focuses.

They both return in Cries and Whispers (1972) (pictured above), which is probably the most powerful, heart-wrenching and perfectly accomplished film in this latest collection. Three sisters are cooped up in a country mansion, that unity of place again giving Bergman’s film such strength. One of them, played by the sublime Harriet Andersson, is dying. The other two manifest different aspects of womanhood, subjects that Bergman devoted himself to with unparalleled empathy: Maria (Liv Ullman), flirtatious, over-sensitive, contrasted with the more reserved Karin (Ingrid Thulin). The servant, Agnes (Kari Sylwan), incarnates a kind of positive mother figure. It is not the first time in Bergman’s films – I am thinking, for instance, of Bibi Andersson in The Seventh Seal (1957) – that innocence and a capacity for love are more likely incarnated in someone from outside the uptight bourgeois world on which he mostly focuses.

The film is characterised (unlike Fanny and Alexander) by an almost monochrome use of colour, with a saturated red – the drapes and upholstery, in particular – contrasted with the pure white of long dresses and bedsheets. As with many of his films, Bergman uses sound exquisitely as well as music (in this case Bach and Chopin) sparingly, never upstaging the essentially visual unfolding of the story. This is one of those films that I first saw on its release, whose atmosphere and images have become firmly imbedded in my psyche – a rare thing.

Fårö Document (1970), one of Bergman’s few documentaries, is the second to explore the ordinary people of Fårö, the bleak island where he would retreat to write, and where some of his most famous films – Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Hour of the Wolf (1968), Shame (1968), Persona (1966), The Passion of Anna (1969), The Touch (1971) – were shot. The focus here is on the island’s population, shown in their bleak landscape – Bergman exploring lives that are dedicated to hard labour, or facing a lack of opportunities and the encroachment of tourism.

There is a humanity here, but also a world, examined in its social context, that rarely impinges on the director’s predominantly chamber fiction. Although it is beautifully shot by Nykvist, there is something inept about the film, a lack of pacing and surprisingly inconsequential editing. There is none of the master's usual elegance or formal brilliance, as if the real world might in some way be devoid of the theatre and magic of the imagination: something that this sorcerer of the cinema knew how to conjure so well.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Add comment