Best of 2022: Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Best of 2022: Theatre

Best of 2022: Theatre

In an iffy year for new plays and musicals, a post-pandemic London stage returned to life

Where were the great new plays during 2022? That question underscored weeks of playgoing that turned into months, with very little new British writing announcing itself with real force.

Three of the best are enumerated further down, but the disappointments were many: David Hare's talky Straight Line Crazy, a fascinating topic (the American urban planner Robert Moses) that existed primarily to showcase Ralph Fiennes in barnstorming form. Or Mike Bartlett's often-ludicrous The 47th, another play redeemed by a startling central performance – in this case, Bertie Carvel as, of all people, Donald Trump – that dared to see the 45th American president in something resembling the round. What a pity the play's prognostications (Kamala Harris as the coming Democratic presidential nominee: really?) made little sense.

Richard Eyre, the distinguished director who led the National in glory, faltered as playwright with the undercast, strangely plotted The Snail House, while Beth Steel, author of a glorious Hampstead entry of old, the all-male "work play" Wonderland, allowed ambition to outstrip achievement with her Almeida premiere, The House of Shades. April De Angelis's Kerry Jackson didn't so much anatomise toxic behaviour as play it for cheap laughs even as, on the musical front, the Young Vic premiere of Mandela did paper-thin disservice to the mighty legacy of its eponymous pioneer.

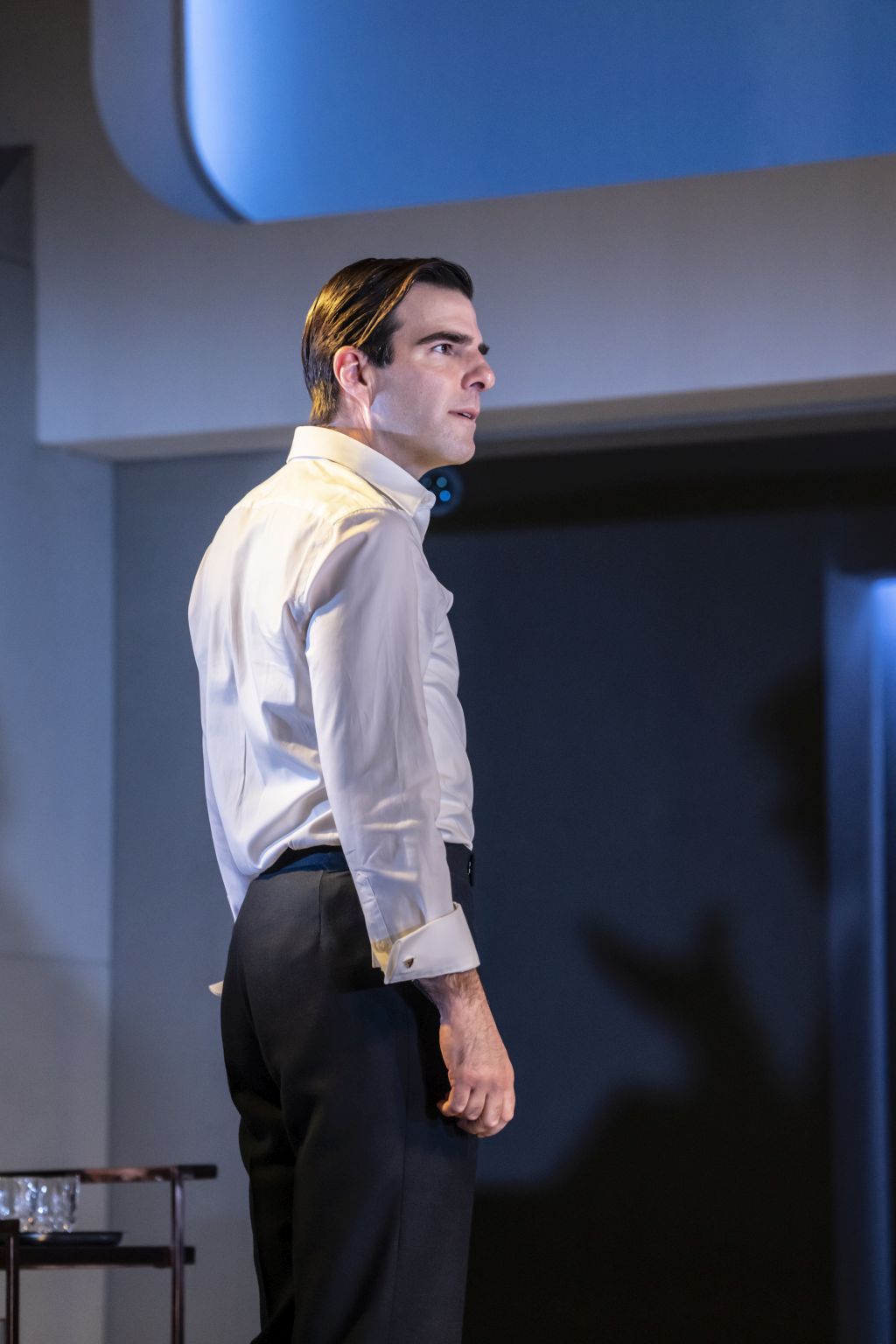

Recastings allowed one to assess previously admired productions afresh: Victoria Hamilton-Barritt brought a forbidding power to the reboot of the National's mess of a musical, Hex, even if one missed the star wattage of Rosalie Craig in the demanding central role of Fairy. Callum Scott Howells, the young Welshman from TV's It's A Sin, astonished as the Emcee in Cabaret en route to his own National stint in February in Romeo and Julie, whilst Zachary Quinto (pictured left by Johan Persson) took over from Olivier nominee Charles Edwards in Best of Enemies and gave off a darker, crueller vibe where Edwards was correspondingly svelte and smooth.

Recastings allowed one to assess previously admired productions afresh: Victoria Hamilton-Barritt brought a forbidding power to the reboot of the National's mess of a musical, Hex, even if one missed the star wattage of Rosalie Craig in the demanding central role of Fairy. Callum Scott Howells, the young Welshman from TV's It's A Sin, astonished as the Emcee in Cabaret en route to his own National stint in February in Romeo and Julie, whilst Zachary Quinto (pictured left by Johan Persson) took over from Olivier nominee Charles Edwards in Best of Enemies and gave off a darker, crueller vibe where Edwards was correspondingly svelte and smooth.

Happily, the volume of openings in the capital was back in force (December's rush of press nights had critics racing to catch up): any post-pandemic caution seemed to have abated, and, with it, the last-minute closings and cancellations prompted by Covid that marked out this time last year. (Two high-profile London shows, Watch on the Rhine and A Streetcar Named Desire, delayed their openings into 2023 for unrelated reasons.) And the acting often was top-notch even when the plays sometimes were not. What follows is an inevitably highly personal list of ten nights (or matinees) during the year just gone where, for whatever alchemical reason, everything magically coalesced and art, as it should, gave renewed shape and definition to life.

As You Like It, @Sohoplace

Central London's first new large-scale theatre in a half-century opened in the autumn with the inaptly titled Marvellous, only to redeem itself with Josie Rourke's luminous, visually lush take on Shakespeare's bewitching comedy. Sure, Leah Harvey is hardly "more than common tall" as that most magnetic of heroines, Rosalind, but the alumna of the National's wonderful Small Island anchored a production alive to diversity that included Alfred Enoch as the sweetly besotted Orlando; American actress Martha Plimpton (now based in London) as a peppery, spryly spoken Jaques; a bespectacled Tom Mison in a welcome return to the stage as the ever-jocular Touchstone; and the deaf actress Rose Ayling-Ellis as a BSL-speaking Celia whose gift for enchantment was representative of the staging as a whole.

Blackout Songs, Hampstead Downstairs

Joe White's two-hander arrived at the Hampstead's intimate basement theatre just in time to remind us of the importance within the theatrical ecosystem of a new writing theatre that saw its government funding cut by 100 percent in the autumn, as was also true at the Donmar and the Gate. And while the Hampstead mainstage had a tough year qualitatively, its downstairs studio space swelled with emotion. That affective uptick was due, at the start of 2022, to Nell Leyshon's fulsomely imagined Folk, followed late in the year by White's unsparing view of a love affair plagued by alcohol and acted to the hilt by Rebecca Humphries and the mesmerically mercurial Alex Austin: not since Constellations at the Royal Court Upstairs has a small-scale play looked so ready to go the distance.

Blues for an Alabama Sky, National Theatre / Lyttelton

Blues for an Alabama Sky, National Theatre / Lyttelton

It's been remarked more than once that the director Lynette Linton, now in fine, firm charge of the Bush, may end up one day running the National. Who can say just now what will happen, but she certainly made a galvanic first impression at that address, locating in American writer Pearl Cleage's 1995 play a rending study in dreams deferred worthy of Lorraine Hansberry on the one hand, Tennessee Williams on the other. Focusing on adjacent apartments in 1930s Harlem populated by a vivid cross-section of artists and activists, Blues was shot through with a mournfulness indicated in the title, punctuated at the same time with ribald, freewheeling comedy and a cast (headed by Giles Terera and American Emmy winner Samira Wiley, pictured right by Marc Brenner) able to honour fully every textual swerve and shift in mood.

Mother Goose, Duke of York's Theatre

Was there a more delightful matriarch on view all year than a gleaming-eyed octogenarian called Caroline Goose? I doubt it, especially in the capaciously full-figured form of a flamboyantly curlered and wigged Ian McKellen in a Jonathan Harvey panto that was perhaps the year's most purely enjoyable evening. Packing in musical references aplenty, from A Chorus Line and Funny Girl to Right Said Fred, Cal McCrystal's exuberant production coupled political zingers with real heart, and was gifted with a cast (John Bishop and Anna-Jane Casey chief amongst them) that looked as if they were having the time of their life, an indefatigable McKellen – soon to be 84 – leading the irresistible charge.

A Number, Old Vic Theatre

Caryl Churchill's onetime Royal Court play has ricocheted out into the world in any number of fine revivals, including one at the Bridge Theatre just prior to the pandemic. But none since the Stephen Daldry-directed original had the brute force of Lyndsey Turner's devastating reappraisal for the Old Vic, which relocated the final scene in an art gallery so as to widen out yet further the play's enquiry into nothing less than existence and what is it that makes us who we are. Employing four actors instead of the usual two, the production revealed Lennie James and Paapa Essiedu as the double-act of the year, or perhaps one should say quadruple-act given Essiedu's astonishing occupancy of three cloned sons of the abject father, played with a roiling sense of self-reproach by a career-best James. Turner's invaluable designer, as ever, was the ceaselessly imaginative Es Devlin, whose set gave visual force to the vexed issue of identity that courses through Churchill's magisterially terse, teasing text.

Oklahoma!, Young Vic Theatre

It's 30 years, incredible though it may seem, since Nicholas Hytner premiered his National Theatre Carousel, which to this day remains the best Rodgers and Hammerstein revival I expect ever to see. But Daniel Fish's take-no-prisoners take on the pair's earlier Oklahoma!, directed alongside Jordan Fein, comes a close second in a possibly historic trajectory that dates back to its inception on an American college campus 16 years ago. The London cast combined holdovers from New York with London newcomers, amongst whom Anoushka Lucas (author-actor of the superb Bush Theatre entry, Elephant) shone as the farm girl Laurey alongside the straight-haired Curly of Arthur Darvill. But the ongoing revelation was London stage newbie Patrick Vaill as the Jud Fry of Laurey's disturbed, erotically complicated dreams in a performance that made the play's central triangle at once dangerous and sexy, the musical's explosive throughline from love through to loss on troubling view for all to see.

Patriots, Almeida Theatre

Patriots, Almeida Theatre

The Russian president Vladimir Putin continues to make horrific headlines but was at the chilling centre of Peter Morgan's entirely absorbing history play, as incarnated with icy, vainglorious command by the excellent Will Keen (pictured left by Marc Brenner). Rupert Goold's skilled production gave pride of place to Tom Hollander in characteristically alert, engaged form as the displaced oligarch, Boris Berezovsky, on the road to (probably-suicidal) ruin, but one's attention was diverted time and again to Keen stiffening in posture as Putin gained in power: between this performance, and Carvel's Trump (also directed by Goold), these hard men of modern-day politics were given cunning, commanding stage life.

Red Pitch, Bush Theatre

Black men mattered, and then some, on the London stage this year, from the return of Ryan Cameron's furious and funny For Black Guys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy (seen this time out at the Royal Court) to the Bush Theatre premiere of Tyrell Williams' dazzling portrait of three south Londoners playing out their aspirations, and tensions, on the football pitch. Under Daniel Bailey's expert direction, the Bush was reconfigured so that we seemed to be forever mid-match with an irresistible trio of young men brought to compassionate and clear-eyed life by Emeka Sesay, Kedar Williams-Stirling, and the blazing Francis Lovehall, in a star-making turn. Across 90 unbroken minutes, we gained an understanding not just of the trio on view but of a broad array of people, and situations, that the play speaks of but doesn't show: if ever a play were ripe for a TV adaptation, and elaboration, this is it – just so long as Williams keeps writing so winningly for the stage.

The Seagull, Harold Pinter Theatre

Jamie Lloyd's stripped-back, laser-sharp take on Chekhov's 1896 play was up and running but hadn't yet opened when the pandemic hit in spring 2020, only to open belatedly more than two years later, the actors' interplay presumably only deepened by time. Unfolding on a chipboard set that gave way to reveal an inky blackness beyond, Lloyd's approach to the first of Chekhov's four great masterworks wasn't one for the purists, any more than was Oklahoma! above. The result often felt like an x-ray of the play, performed with correspondingly forensic power by Indira Varma in glorious form as the self-regarding Arkadina; a haunted Daniel Monks as her emotionally stunted son Konstantin; Tom Rhys Harries as an eye-catching and younger-than-usual Trigorin; and, making a luminous West End debut, Game of Thrones' Emilia Clarke as the young actress at the fraught vortex of the others' deeply competitive attention.  Tammy Faye, Almeida Theatre

Tammy Faye, Almeida Theatre

Talk about a rebound; Elton John suffered the slings and arrows of critical misfortune with the Chicago tryout of The Devil Wears Prada, which has been derailed at least for now en route to Broadway. But the rocketman was in vintage form with this new musical about a much-chronicled female American icon, Tammy Faye Bakker, whose screen incarnation brought an Oscar to Jessica Chastain just as this musical version looks set to pack leading lady Katie Brayben's shelf with awards in due course. (Brayben, pictured above by Marc Brennan, already has an Olivier for playing Carole King in Beautiful.) A busy Rupert Goold's production could benefit from trimming and tightening but amidst a generally dismal year for new musicals, Tammy Faye was a giddy surprise: satiric where needed but also deeply serious about the legacy of a God-fearing, gay-friendly Christian who has earned a particular place for herself in the American zeitgeist.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

That Bastard, Puccini!, Park Theatre review - inventive comic staging of the battle of the Bohèmes

James Inverne enjoyably reconstructs the rivalry between Puccini and Leoncavallo

That Bastard, Puccini!, Park Theatre review - inventive comic staging of the battle of the Bohèmes

James Inverne enjoyably reconstructs the rivalry between Puccini and Leoncavallo

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Girl From The North Country, Old Vic review - Dylan's songs fail to lift the mood

Fragmented, cliched story rescued by tremendous acting, singing and music

Girl From The North Country, Old Vic review - Dylan's songs fail to lift the mood

Fragmented, cliched story rescued by tremendous acting, singing and music

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare's Globe review - hedonistic fizz for a summer's evening

Emma Pallant and Katherine Pearce are formidable opponents to Falstaff's buffoonery

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare's Globe review - hedonistic fizz for a summer's evening

Emma Pallant and Katherine Pearce are formidable opponents to Falstaff's buffoonery

Run Sister Run, Arcola Theatre review - emphatic emotions, overwrought production

Chloë Moss’s latest play about the different lives of two sisters is deeply felt

Run Sister Run, Arcola Theatre review - emphatic emotions, overwrought production

Chloë Moss’s latest play about the different lives of two sisters is deeply felt

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Add comment