Hopper: An American Love Story review - a dry view of a much richer subject | reviews, news & interviews

Hopper: An American Love Story review - a dry view of a much richer subject

Hopper: An American Love Story review - a dry view of a much richer subject

The inscrutable American artist gets the cinema treatment in a conventional biography

This rather disappointing documentary about the great American painter Edward Hopper (1882-1967) has such a dry parade of experts and such a slow linear narrative that it leaves plenty of time to be frustrated by all that’s been left out.

Made by the veteran arts documentarian Phil Grabsky for the Exhibition on Screen series, the film features undated on-camera interviews with Hopper and his wife. How difficult would it have been to caption them with a date and a source? And despite following a conventional chronological structure – birth to death – we don’t get much sense of when Hopper became such a huge success or much art historical context. Given the 90-minute duration, some detailed analysis of his techniques – he worked in oils, watercolours and etching – would also have been welcome.

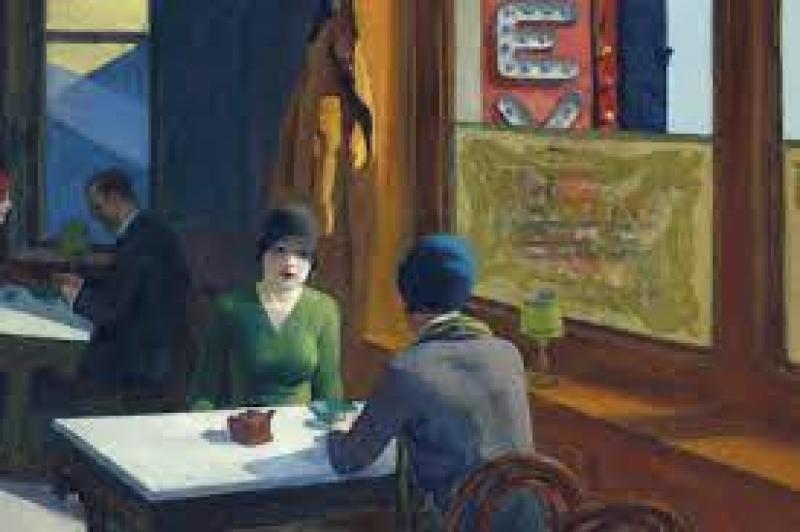

An introverted intellectual whose interest in people was as spare as their appearances in his paintings, Hopper created iconic images that stay in the mind because of their enigmatic compositions. He was fascinated by the play of light on architecture and passionate about the cinema, and his work has exerted its own influence on film directors and artists.

Grabsky has some fresh material about the young Hopper's thwarted love affair with Alta Hilsdale, but his combative marriage to painter Josephine Nivison is well-known territory. Gail Levin’s excellent 2007 book Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography mined Nivison’s diaries and papers to paint a vivid portrait of their difficult relationship.

Nivison was Hopper's great support. She promoted his work to dealers and museums when he was unhappily making a living as a commercial illustrator in the 1920s. Once they were married, Nivison – who chronicled their often argumentative relationship – effectively acted as Hopper's manager, modelling for him also.

The film gives a strong sense of the frustration she experienced in sidelining her own work as an artist in order to champion Hopper's career. Alongside that frustration runs her fierce pride in her husband's work. At one point, she describes his paintings as their children, who must be hung on white walls and protected from the bleaching rays of the sun.

There are some good sequences when Grabsky’s camera visits Hopper’s family home in Nyack in Upstate New York and later Gloucester in Massachusetts, where the couple built a retreat from the city. Most of their time was spent in the cramped walk-up studio on Washington Square that they shared for over 30 years.

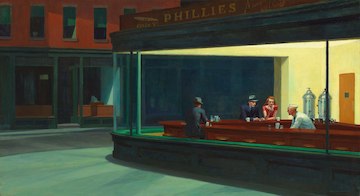

Revisiting the locations of some of Hopper’s eerier paintings, made when the couple took road trips together, leads to some fine juxtapositions between Hopper’s work and the real world. But the most intriguing pictures are the ones that are not directly painted from life but improvised from memory and influenced by Hopper's love of the movies, particularly film noir.  Hopper's Nighthawks (pictured above) has become one of the most recognisable paintings in America, subject to homage and parody. It’s a shame that the commentators in Hopper: An American Love Story have so little of interest to say about its ambiguity.

Hopper's Nighthawks (pictured above) has become one of the most recognisable paintings in America, subject to homage and parody. It’s a shame that the commentators in Hopper: An American Love Story have so little of interest to say about its ambiguity.

One academic comments that it’s part of the painting's mystery that there’s no knob on the door from the bar to the kitchen, but surely it’s a swing door that allows a server with their hands full to push it open? The repeated observations by another interviewee about the lack of ethnic diversity in the people Hopper painted seems like a box-ticking exercise for a 2022 audience.

The noodling score doesn’t do much to enhance the parade of commentators, archival materials and slow close-ups of the art. The generic music is not of the period and adds to the impression that this documentary belongs in a side room of a museum showing a Hopper retrospective, rather than deserving a visit to a cinema.

Hopper admirers might find it more worthwhile to rummage on the internet instead for the BBC’s 2004 Imagine: The Mysterious Mr Hopper, directed by Ian McMillan, with its excellent, insightful interviews with Levin, Jonathan Miller and Sam Mendes, among others. It covers the same difficult marriage story but deploys the sly caricatures Hopper left for his wife after a row to tell the story visually with a lightness of touch and humour this new documentary lacks.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment