theartsdesk Q&A: Horn player Sarah Willis on returning to Cuba | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Horn player Sarah Willis on returning to Cuba

theartsdesk Q&A: Horn player Sarah Willis on returning to Cuba

Guaguancós, cha-cha-chas and crickets as the horn player commissions a new work in Havana

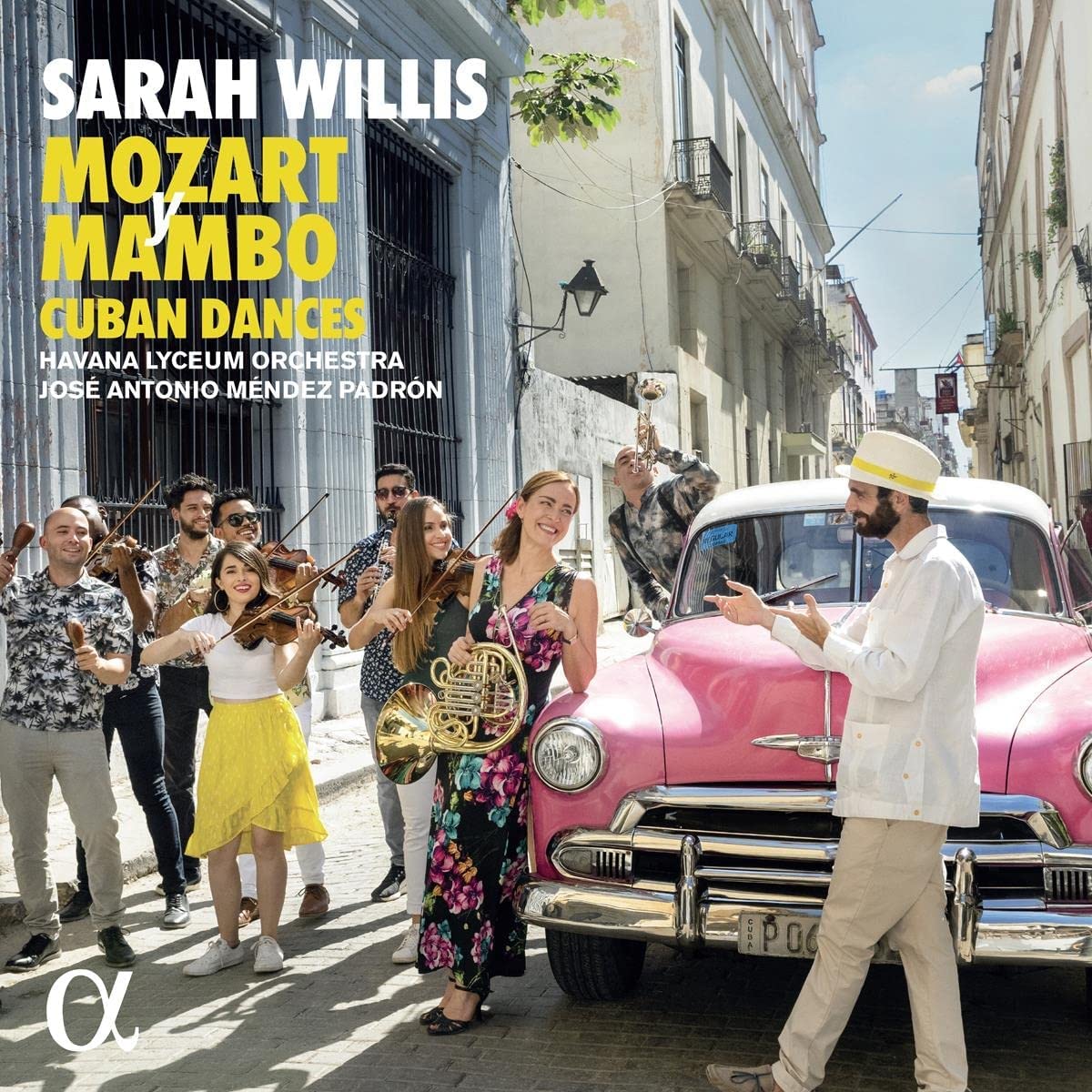

Berlin Philharmonic Horn player Sarah Willis’s Mozart y Mambo caused a stir in 2020, its mixture of Mozart and traditional Cuban music making it a bestselling crossover disc.

Two years on and the second volume has just been released, the sessions held in Havana in January and April this year. As with the first album, a percentage of the proceeds will go towards raising money for new instruments for the Havana Lyceum Orchestra. We discussed the project over Zoom in August.

What prompted you to record a second CD?

Second albums are notoriously difficult! The mixture of Mozart and mambo proved incredibly popular first-time round. There were more horn concertos to record, but I didn’t want to go to back to Cuba and then disappear; I wanted to leave something behind. I suddenly thought; wouldn’t it be wonderful to carry on this journey into Cuban music? I will commission a Cuban horn concerto, and maybe people will remember me for generations when they play it.

The centrepiece is a portmanteau work, written by six composers – how did it come about?

The centrepiece is a portmanteau work, written by six composers – how did it come about?

Mozart y Mambo has been a big thing in Cuba; it’s become a real project, something that’s given us hope. Life there has been very difficult recently, and for many of my musicians, this has been the only work they’ve had during the pandemic. So we had a little composition competition in Cuba, as I knew some talented classical composers. There’s no tradition of writing for the horn in Cuba; I don’t think it’s an instrument that’s been understood. Trumpets, and trombones, yes – but not the horn. I wanted solo horn with strings and percussion, and asked entrants for a minute of music. Most of the composers sent a MIDI file, and I had so many fantastic entries that the concerto became a six-movement suite. Each section was so different, each composer writing an original work set to a traditional Cuban rhythm. There’s a lot going on in this piece – not least the fact that the composers had to learn to notate their ideas. We’re using rhythms like the Changüí which just aren’t written down.

What was it like to play this music for the first time?

Some of the musicians said I should have had a co-composer credit, as lots of the scores had to be picked apart, and there wasn’t a secure understanding of what the horn can do. I wanted other people to play these works. They’re very challenging, but playable. Each composer had their own crazy way of seeing things. Listen to the last movement’s Changüí. The first 16 bars sound like a really nice tune, and then the percussion comes in and it’s like a big hiccup. I looked at the score and found that I’m always on the offbeat!

Sometimes you complicate things by notating them!

You’ve just described Cuban music. They don’t write it down, because they prefer to feel it. I sent the score to my brother, who’s a conductor in the US, and asked him if his orchestra could play the finale. “Absolutely not!” was his response. I was worried that maybe people wouldn’t want to play the piece because of the last movement, so I decided to offer an alternative ending. I asked two of the composers to write something using my favourite rhythms, the cha-cha-cha and the mambo. So you can either finish with the “Sarahchá”, or, if you’re feeling brave, carry on with the “Changüí”.

Did all six composers get together to share their work?

Absolutely. We assembled in Havana for a day, and played each movement, filming them for an Arte documentary. I was nervous playing these works for the first time, even though I’d worked with each composer quite closely. Cuban Dances is a difficult concerto, but a playable one. The thing which really switched me on was a comment from composer Yuniet Lombida, who told me that I wasn't going to be able to play it if I didn't learn how to dance it. I thought I was quite a good salsa dancer, but when you try and learn guaguancó or Changüí, you have a completely different understanding, a different feeling in your body. We filmed each separate piece in the area where each dance comes from.

Was the return trip to Cuba an emotional experience?

It was like going back to my family. We had to record at night until 2 or 3am because there was much noise in the street outside: dogs, cats, singing and reggaeton. A little cricket found his way onto the album, and if you listen carefully you can still hear him chirping on one of the tracks. When we reached the very last note of the very last recording, there were so many tears, but tears of joy. We decided to subtitle the album Cuban Dances, as Mozart’s K417 is the most danceable of his horn concertos. There are also two songs, each one beautifully arranged by Jorge Aragón. He knows and understands my playing and he’s a genius, one who wants to be the next John Williams. It’s important that the numbers I play aren’t just some foreigner’s idea of a melody with a Cuban beat shoved over it. I always wanted the Cubans, when they heard the album, to go “wow – that’s great!”.

The first album has had some publicity in Cuba, even though my ensemble is not one of the official orchestras. When the government saw how successful it was, we received support from the official Cuban Institute of Music. This makes life a lot easier with visas and travel; bringing my production team from Berlin was fine as they know us. Mozart y Mambo is no longer just a recording; it’s the Instruments Donation Fund, and financial aid for young Cuban musicians. We’re trying to set up an academy, and we’re helping fund some Cuban music students who are studying abroad. At some point we’ll have a Havana Lyceum Orchestra in Europe.

This album is a labour of love. I’m not a principal horn, and I much prefer being a tutti player in the section. To be out there in front of an orchestra, playing concertos for the first album took a lot of courage. I can talk into a camera for hours, but standing up as a soloist after 20 years of not doing it – ouch! The Lyceum Orchestra is a true family, one in which I felt 100% loved and supported.

- Mozart y Mambo: Cuban Dances will be reviewed by Sebastian Scotney next week

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Add comment