A Number, Old Vic review - revelatory yet again | reviews, news & interviews

A Number, Old Vic review - revelatory yet again

A Number, Old Vic review - revelatory yet again

Caryl Churchill's 2002 masterwork resonates anew

Time continues to be kind to A Number, the astonishing 2002 play by Caryl Churchill that reaps fresh rewards with every viewing.

This play can withstand varying degrees of realism, having been birthed at the Royal Court in a scalpel-sharp rendition from Stephen Daldry that was pretty much entirely abstract. Turner, by contrast, gives us a realistic (up to a point) setting from the ever-expert Es Devlin in which Salter (Lennie James) can greet several of his various progeny. Departing from convention, the two women then locate the final scene in an art gallery adorned with blank canvases, a perfect visual metaphor for the enquiry into identity that Churchill's tale of murder and metaphysics has by then become.

That textual strand is clear from an opening conversation in which B2 (Paapa Essiedu), one of what we discover to be a number of sons of the emotionally abject Salter (Lennie James), insists on his siblings being referred to as "people", not "things" or even "copies" to quote the words preferred by a father seen to be reeling from the reality of genetic cloning. And so we're off on a series of face-offs, five in all, that wend a sometimes darkly funny way to a fiercely moving conclusion that ends with an apology for the simple fact of being happy that sends the audience reeling into the night.

That textual strand is clear from an opening conversation in which B2 (Paapa Essiedu), one of what we discover to be a number of sons of the emotionally abject Salter (Lennie James), insists on his siblings being referred to as "people", not "things" or even "copies" to quote the words preferred by a father seen to be reeling from the reality of genetic cloning. And so we're off on a series of face-offs, five in all, that wend a sometimes darkly funny way to a fiercely moving conclusion that ends with an apology for the simple fact of being happy that sends the audience reeling into the night.

"Most people are happy I read in the paper," reports the older son, B1, whom we meet in the second scene. "Keep looking, look," he admonishes a father whom this child takes to task for onetime neglect in an admonition that throws down the gauntlet to the playgoer to stare hard and long into the unflinching minimalism that is Churchill's signature method.

Each of these sons makes an encore appearance on the way to a ruinous finish that won't be revealed for those unfamiliar to the unsparing trajectory of a text with one foot in scientific experimentation and another in something far scarier and less tangible. So it comes as comic relief, in this iteration especially, to be greeted in the brief final scene by yet another son, Michael, this one sporting an American accent and happy-go-lucky mien to match. Essiedu has a field day differentiating the three children, a task accomplished two decades ago by Daniel Craig without a single costume change. "Who is is that can tell me who I am?" asks Lear, a question that seeps into every corner of this play, too, which comes saturated in the red of bloodlines but also of blood by the fierce lighting of the invaluable Tim Lutkin.

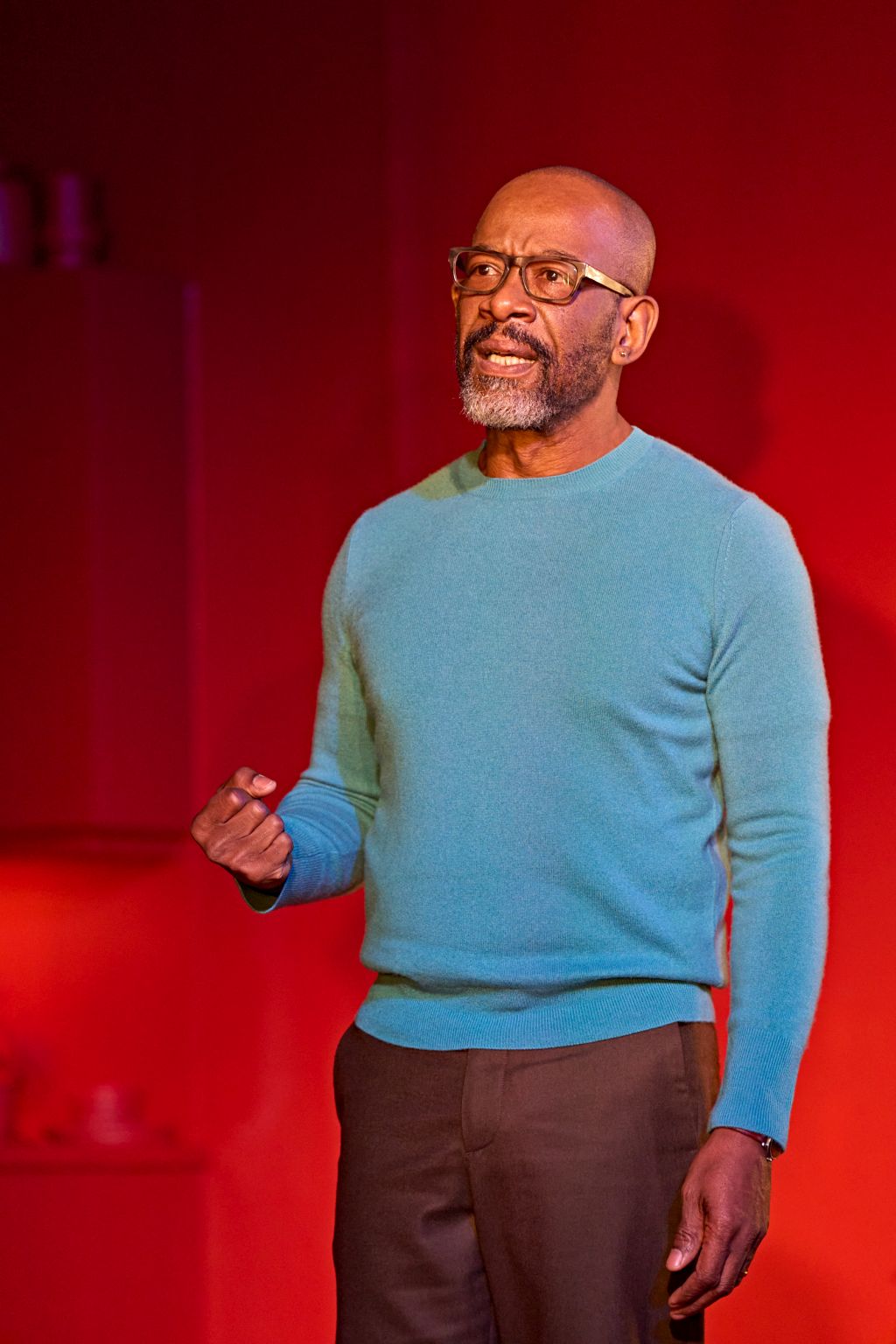

Marking a return to the London stage after 16 years, James (pictured above) has the more reactive part, as Salter engages in a self-reckoning that requires the older man to "really look". A popular figure on American TV since he last trod the boards in London, James brilliantly locates that landscape in the play where language leaves off and grief and remorse take over. Such depths, in turn, seem alien to the frizzy-haired Michael, a maths teacher with three children who "can't help feeling wonderful" much to the amalgam of envy and bewilderment felt by his father.

In a deceptively simple play of innumerable layers, A Number doesn't need the addition of further people late on that might make newcomers to the script think that yet more sons are being paraded before us. (For what it's worth, this version, at only 65 minutes, runs ten minutes longer than did the revival at the Bridge.) The jagged soundscape punctuated by scene changes that quite literally crackle with electricity suggests a modernist composition in five movements, with Churchill's play making its own eerily compelling music. I left the theatre punchdrunk with admiration at the embrace of human mystery that is this writer's ongoing theme and eager to return to its fearless fold as often as any playhouse chooses to plumb A Number's countless depths once more.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Add comment