The Seven Pomegranate Seeds, Rose Theatre, Kingston review - misogynist Euripides stands corrected | reviews, news & interviews

The Seven Pomegranate Seeds, Rose Theatre, Kingston review - misogynist Euripides stands corrected

The Seven Pomegranate Seeds, Rose Theatre, Kingston review - misogynist Euripides stands corrected

Pierce Brosnan's James Bond finds a daft but apt place in Euripidean rewrite

The resurrection of female voices from ancient Greek myth is so common now that one might imagine a grand panjandrum behind the scenes had set down a long-range mission – rather as they do in the fashion industry – which makers and producers scurried to fulfil.

Just a year after the Jermyn Street Theatre’s 15 Heroines put old Ovidian wine into new bottles, many of the same mythical women return in Colin Teevan’s The Seven Pomegranate Seeds, premiered at Kingston’s Rose Theatre, this time germinated from Euripides. (The title refers to the snack eaten by Persephone, abducted by the god of the underworld Hades, which meant she could only return for half a year to the earth ruled by her mother, Demeter, goddess of agriculture and domestic plenty - hence the summer/winter seasons.)

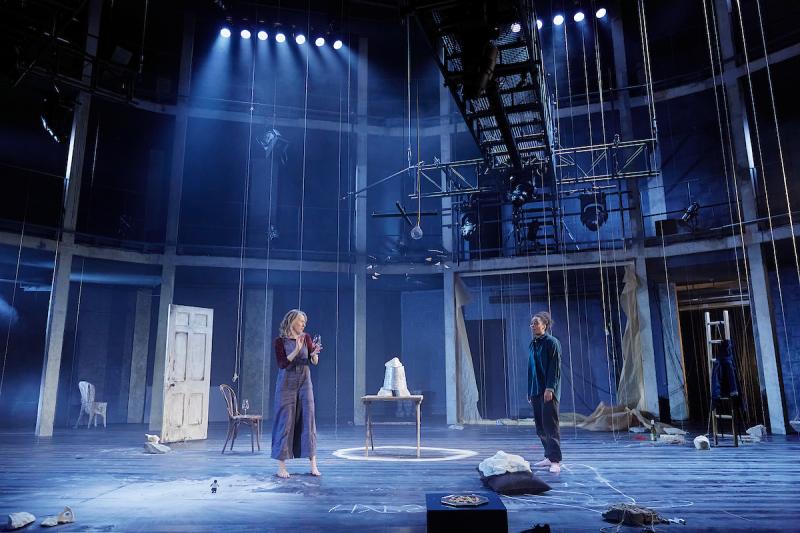

While Melly Still decks the Rose's hall beguilingly like a witch’s cave of memory charms, The Seven Pomegranate Seeds declares its classical antecedents, being, in effect, a declaimed narrative in seven stanzas, delivered by two actors.

That’s fine in many ways, given the compelling performance by the brilliant Niamh Cusack and the impressive young Shannon Hayes (pictured right), and Still’s arresting mise-en-scène. The auditorium is a forest of taut strings, lashing Covid-empty seats to the ceiling, the threads surrounding you in your chair - labyrinths and Ariadne’s thread come at once to mind.

That’s fine in many ways, given the compelling performance by the brilliant Niamh Cusack and the impressive young Shannon Hayes (pictured right), and Still’s arresting mise-en-scène. The auditorium is a forest of taut strings, lashing Covid-empty seats to the ceiling, the threads surrounding you in your chair - labyrinths and Ariadne’s thread come at once to mind.

The strings also tether seven large stones that swing over the stage, which Cusack and Hayes scissor down thuddingly between each of the episodes, aural and visual full stops between the women: the lost Persephone and her bereaved mother Demeter, the neglectful Hypsipyle, tormented Phaedra and Creusa, the over-trusting Alcestis, and the abused Medea.

These capsule stories could slot tidily into Vera, The Archers or Midsomer Murders

Ah yes, the abused, rather than the abusing, Medea. Teevan’s upending of myth’s famous sorceress from a bitter wife who murders her children to the victim of a coercive husband who destroys himself and their children is the key to the theme of this package of female suffering.

The Irish playwright’s “conversation with Euripides” (as the play is described) strains to reverse the 5th-century BCE dramatist’s perception as a misogynist, even to correct him. These capsule stories could slot tidily into Vera, The Archers or Midsomer Murders (Teevan, apart from his long engagement with adapting classical Greek drama, is presently busy in TV drama too).

The populism is enjoyable enough, though modern tropes are just as limiting as the classical archetypes they override. The child Persephone’s expressive, archaic monologue as she dashes through meadows of field flowers and happiness and is dreadfully snatched into the dark is succeeded, with a jolt, by Washington DC childminder Hypsipyle, glued to her iPhone rap-chat, ignoring the screaming brat in her charge until she loses her temper in a fatal flash.

Hypsipyle offsets the wretched Creusa, who must listen to her dinner party hosts’ bragging about adopting a Syrian baby while remembering her own teenaged nightmare of pregnancy and enforced adoption of the only child she could ever have had.

Hypsipyle offsets the wretched Creusa, who must listen to her dinner party hosts’ bragging about adopting a Syrian baby while remembering her own teenaged nightmare of pregnancy and enforced adoption of the only child she could ever have had.

Teevan daftly, pleasingly, calls up Pierce Brosnan’s James Bond as the rescuing hero in the tale of Alcestis who unwisely donates part of her liver to her undeserving husband. (It's Heracles in the original.)

Phaedra, whose half-brother was the Minotaur, provides the excuse for a really funny story about the Lady Mayoress of Pilkington and a pantomime horse.

Fluent, well crafted and often amusing it is, but... rich entitlement, Catholic convent abuse, US democracy abuse, police misconduct, celebrity vanity – there are a lot of easy contemporary targets hit along the way when one can more rewardingly reflect on the men behind these myths, those so-called heroes.

Most of the women here are connected to either Jason or Theseus. Jason married Medea and Hypsipyle. After seducing and abandoning Ariadne, Theseus later married her younger sister Phaedra. Medea married Theseus’s father after her lethal liaison with Jason. They would mostly have known each other, gods and humans, in a cosmos of sexual politics far more convoluted than those of today, and what a soap opera of warring, murdering family feuds and obsessions it would make.

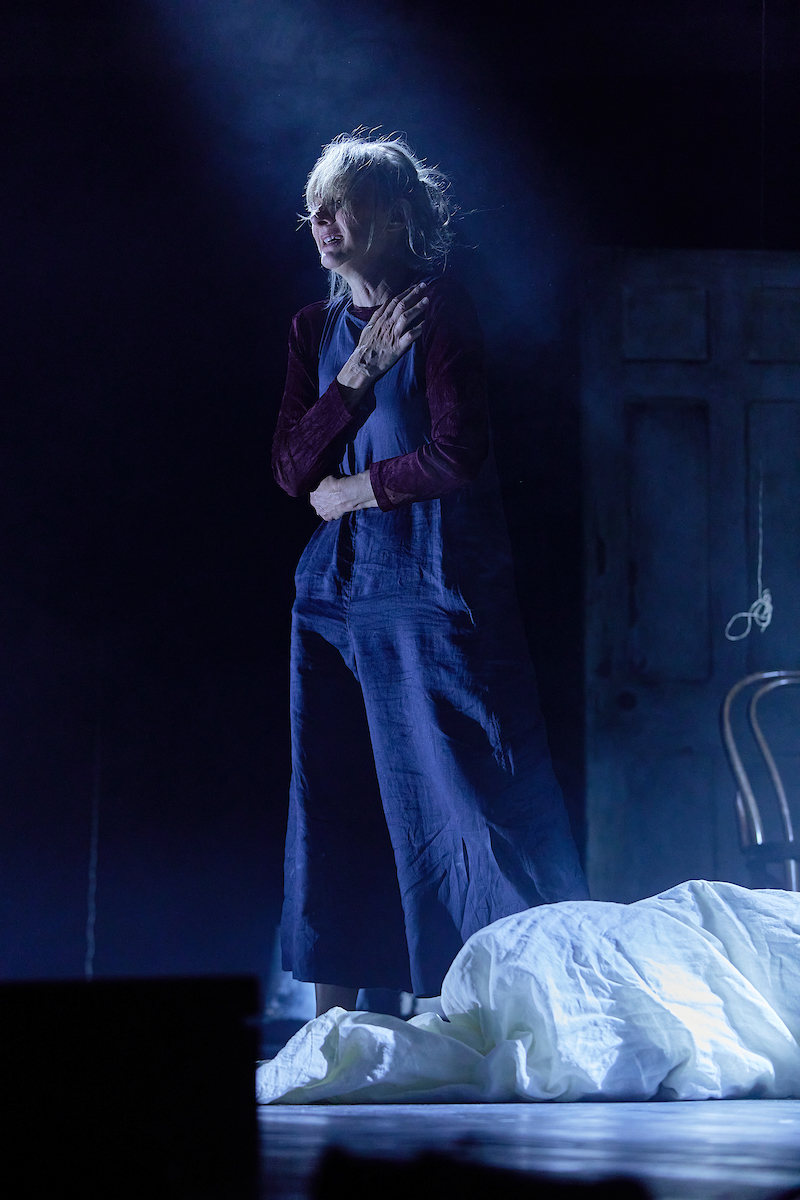

Still, one can be thoroughly distracted by Cusack, in particular (pictured above), who is radiant, wild and heartbreaking, steering the cycle from lost child to found child with a touching spontaneity, while wearing truly hideous dungarees.

- The Seven Pomegranate Seeds, Rose Theatre, Kingston, till 20 November

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Girl From The North Country, Old Vic review - Dylan's songs fail to lift the mood

Fragmented, cliched story rescued by tremendous acting, singing and music

Girl From The North Country, Old Vic review - Dylan's songs fail to lift the mood

Fragmented, cliched story rescued by tremendous acting, singing and music

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare's Globe review - hedonistic fizz for a summer's evening

Emma Pallant and Katherine Pearce are formidable opponents to Falstaff's buffoonery

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare's Globe review - hedonistic fizz for a summer's evening

Emma Pallant and Katherine Pearce are formidable opponents to Falstaff's buffoonery

Run Sister Run, Arcola Theatre review - emphatic emotions, overwrought production

Chloë Moss’s latest play about the different lives of two sisters is deeply felt

Run Sister Run, Arcola Theatre review - emphatic emotions, overwrought production

Chloë Moss’s latest play about the different lives of two sisters is deeply felt

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Add comment