RIP dancer and photographer Colin Jones - obituary | reviews, news & interviews

RIP dancer and photographer Colin Jones - obituary

RIP dancer and photographer Colin Jones - obituary

Dubbed the George Orwell of photojournalism, Jones married Lynn Seymour

In the ballet world, Colin Jones, who died on 22 September aged 85, was famous for being married, for a while, to the great Royal Ballet ballerina Lynn Seymour, during his brief career as a dancer with the company. In the wider world, however, Jones was renowned as a photographer of unusual empathy and social conscience, as well as a striking eye. A Sunday Times critic once described him as "the George Orwell of photojournalism".

Ten years ago I met Colin Jones to talk about a new exhibition of his photographs, and our conversation roamed widely through his childhood experiences as an East End London child, his somewhat fairytale experiences travelling with the Royal Ballet, and his transition into photography. The Q&A appeared in The Arts Desk on 13 January 2011. Jones liked it enough that he had it printed into a brochure to accompany his exhibitions.

Dancers only want to look absolutely perfect in their pictures. To me that wasn't what it was about, it was about the physical work

Colin Jones was part of a legendarily painful triangle. Married to one of the greatest of ballerinas, Lynn Seymour, but constantly edged aside by the brilliant choreographer who was obsessed with her, Kenneth MacMillan, Jones left ballet to become a photographer, and used his unique access and friendships with people such as Rudolf Nureyev to document in unheard-of intimacy and freshness the golden era of the Royal Ballet. Ballet stars in the 1960s were as huge as pop stars, but behind even the most dazzling fame, they were leading the earthy, practical, hardworking lives of touring dancers.

An exhibition has opened this week in Chelsea featuring a gripping selection of photos taken by Jones in the Rudy-Margot era when the Royal Ballet was the biggest act in world culture. His pictures, though, show what was rare in those days: backstage or outdoors photographs of dancers doing ordinary things, the timeless circuit of B&Bs, having drinks in pubs, buying fags and newspapers, and the sheer sweating graft of the studio.

Born in 1936 in the East End of London, Jones (pictured left) had nothing like the background to be expected of a dancer: a wartime child, he was evacuated so often with his family that he reached school-leaving age barely able to read or write, and he seized the chance offered to him to train as a ballet dancer. He joined the Royal Ballet as a youngster just when the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan was embarking on some of his most pivotal, controversially new ballets, inspired by the young ballerina Lynn Seymour. Jones would marry Seymour, and Seymour would abort their child in order to be available for MacMillan’s world premiere of Romeo and Juliet, which had been created for her. But due to commercial pressures, MacMillan allowed Nureyev and Fonteyn to give the premiere instead, devastating Seymour, and costing her and Jones their marriage.

Born in 1936 in the East End of London, Jones (pictured left) had nothing like the background to be expected of a dancer: a wartime child, he was evacuated so often with his family that he reached school-leaving age barely able to read or write, and he seized the chance offered to him to train as a ballet dancer. He joined the Royal Ballet as a youngster just when the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan was embarking on some of his most pivotal, controversially new ballets, inspired by the young ballerina Lynn Seymour. Jones would marry Seymour, and Seymour would abort their child in order to be available for MacMillan’s world premiere of Romeo and Juliet, which had been created for her. But due to commercial pressures, MacMillan allowed Nureyev and Fonteyn to give the premiere instead, devastating Seymour, and costing her and Jones their marriage.

Jones went on to an acclaimed career with The Observer from the 1960s on, doing major series and photography books on Leningrad in the Cold War, The Who, the great rivers of the world, northern miners and ballet dancers, and "The Black House", a hostel for black delinquents in London in the 70s, of which his exhibition was so controversial it got vandalised. He married a model, Priscilla, and they have a 37-year-old daughter.

Now 74, he invited me this week to his house in Barnes, and he talked of his very peculiar road into photography, friendship with Nureyev, popstars and great ballerinas, and the challenge of trying to catch that moment in time and movement with a camera.

ISMENE BROWN: Do dancers actually like being photographed?

COLIN JONES: They’re not very keen on you photographing when they’re not looking good. It’s very difficult today. If you work for the ROH, which I did, and if you take pictures of the dancers now, it’s their copyright, they want the copyright. In my day there was no such thing. I prefer dancers backstage, because it’s what the audience never saw, they never saw the hard work these people went through to get to their professional peak, they only saw the glamour. And today dancers only want to look absolutely perfect in their pictures. To me that wasn’t what it was about, it was all about the physical work that they did.

Was that because you as a dancer felt it as hard work, rather than something drawing ideal pictures?

Well, I never really enjoyed being in the company. Towards the end I hated it, I couldn’t wait to get out. I was slightly dyslexic with music and other things, but if you’re not musical… there are a lot of ballerinas even who aren’t musical, but I found it nervewracking.

Did you want to do it well?

Well, yes, I think you do. I had my moments - when Kenneth MacMillan cast me in The Invitation, I suppose I did change a little, but not a lot. I was rebellious. The discipline was amazing, and I’d always been slightly undisciplined. In my earlier life I was always getting into trouble.

Well, yes, I think you do. I had my moments - when Kenneth MacMillan cast me in The Invitation, I suppose I did change a little, but not a lot. I was rebellious. The discipline was amazing, and I’d always been slightly undisciplined. In my earlier life I was always getting into trouble.

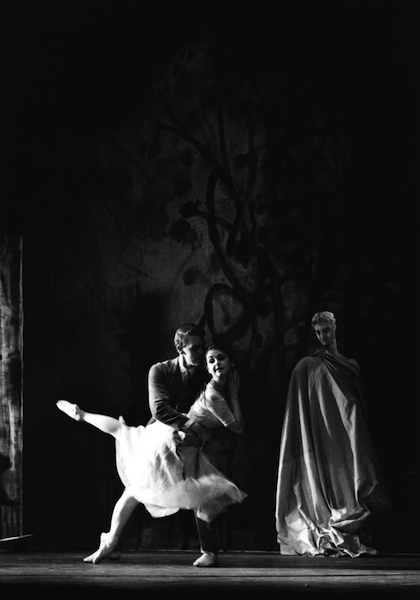

[The Invitation was a shocking, sexually charged work created by MacMillan in 1960 about the rape of a young girl at a garden party. Lynn Seymour played the girl, and after its sensational premiere at the Royal Ballet Touring Company, it was rapidly taken into the main Covent Garden company, making Seymour and MacMillan's name for extremely daring work. Pictured right by Jones, Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable as the innocent teenagers before the attack, 1962]

What drew you into such a disciplined profession then?

Well, what happened was I went to about 13 schools as a kid, because of the war. For example, one school I went to in Woolwich - used to go by the tram. One day I got up, got onto the tram, got to school, and it was a ruin. It had been bombed during the night. I’d only been there two weeks. Being evacuated, I kept moving about.

I can’t imagine a child going through that without being both frustrated and depressed.

It was pure torture to me. We would keep being evacuated, come back to London or wherever. There were lots of sections in the war, at the beginning my father going away, us being evacuated, then coming back, and then the house got bombed, so we went away again to Reading. I didn’t see my father for something like 10 years. I’ve got a younger brother, who has a better memory than I do.

Your mother must have been thinking, Colin will never get a decent education.

Yes, when they saw the bad school reports they would get very upset. Anyway, somebody I got to know who was a teacher at a private school, which was on the road going up to Eltham I think, said they’d let me go there, and I think they didn’t charge. And though I was improving a bit, I still couldn’t really read and write even when I was about 15. Bit like the West Indian community today, there’s a lot of kids who can’t read or write. But I did start a bit at this school. One day the Festival Ballet was doing a demonstration class at school, trying to recruit dancers, and you’d get some kind of grant, I think. I stood up and went on stage, and it didn’t seem too bad to me because I was always slightly athletic. At St Mary’s, Sidcup I’d boxed for the college so I kept quite fit. Sitting in the audience was a dancing teacher from nearby who asked me afterwards if I’d like to become a dancer, I said yes, it was better than being a roadsweeper. I had no education, you see.

You must have been feeling pretty desperate. Because your dad was a printer, wasn’t he?

Yes, he was a bit like me, very talented but never quite knew what to do with it. He’s dead now, but my mother is still alive, she’s over 100 now. That was the choice. I realised that. The thing with extreme dyslexia - nobody knew what it was then - you just can’t get it together with words. I went to her school anyway, she invited me to go to class every day.

You felt wanted there.

Oh, I felt very wanted there! I can’t say her name in case she’s still alive. She’d probably be done for paedophilia.

That’s why she wanted you in her school?

Oh yeah.

And did she get onto you?

Oh yeah.

So that was one of the attractions of the dance world - the sex life.

Oh yeah, it was in the company too. But if I hadn’t done dance I wouldn’t have been where I am now. I can’t remember if I got a scholarship, but the Royal Ballet in those days would have taken a boy with one leg, they were so short of boys.

Ninette de Valois would?

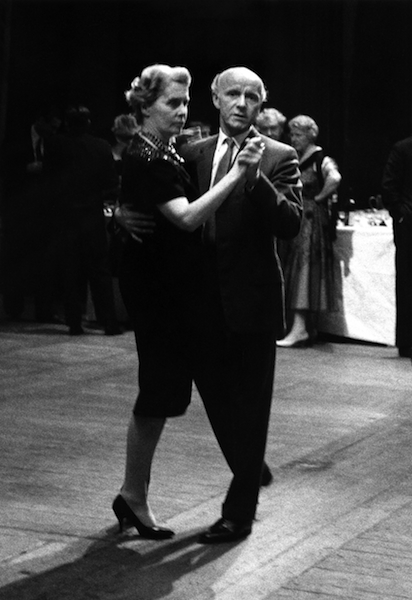

She was a strange woman but rather nice. I mean, she used to like East Enders like me. She was Irish of course, and used to drink a lot of whiskey, which we never knew about at the time. She lived in Barnes, you know, used to be in the Coach and Horses a lot. Have you ever read her poems? There’s one about the pub, the Coach and Horses. (De Valois and Harold Turner pictured below left by Jones in 1961 at an onstage party in the Royal Opera House) We all did live around here because it was cheap in those days. We’d get a bus to Hammersmith, and walk to the school.

When you got into the ballet company, was it a family? Were you seeking affection, in a sense?

When you got into the ballet company, was it a family? Were you seeking affection, in a sense?

Oh yes, it was like a closed community, a convent. You knew lots of secrets that outsiders don’t know but they’re curious about. I was never very good in communities - even now I wouldn’t join Magnum [the photography collective], because I feel unable to cope with communities, my brain won’t work like that. Some photographers only talk about photography. I’m quite political now, for a dancer. I mean, the Opera House is very right-wing and conservative but in those days they used to get away with murder. I mean, it was illegal to be gay, but nobody took any notice of it, and abortion was illegal too - most of the dancers had abortions, and nobody officially knew about it. It was about who you were, a bit corrupt in a sense, but protective.

I joined the company in 1953, then I had to leave to do National Service, so I deferred it for a year, went to work as a farm labourer in Kent, picking apples, and then went into the army, but it was terrible. It was a camp regiment - I told the other dancers, “I’m in the Queens…” It was one of the toughest infantry regiments. The sergeant-major called out, "Which one of you is the ballet dancer?" I stepped forward. And they gave me a terrible time in the barrackroom. All trying to jump into bed. I took up boxing again in the army and they left me alone because they knew that if anybody attacked me I’d kill them. I literally did get stopped nearly killing somebody, bashing his head on the iron bedstead - and I wouldn’t have minded if I had killed him. Because you’re being bullied, and to be bullied is unforgivable. He’d come along and try to stick his dick in my ear, and things. I laid him out. Nobody joined in - they just stood watching.

Did you think about quitting dance when you were there?

Well, the selection officer asked me what I wanted to do after the army… he was gay! A lot of the officers were, you know, that boys’ school type. He told me our regiment was going to Malaysia to fight in the jungle. He told me, "You don’t want to go to the jungle." I said, I don’t know what else to do. He said, "Why don’t you become a physical training instructor?" And I ended up doing that, teaching physical training at the Tower of London. I could live at home when I was doing that.

Did you think about staying in the army and giving up dance?

No, I hated the army. It was like ballet, actually, but much worse. I became acting sergeant, and we’d get invited to do physical demonstrations. All I had when I left was two demob suits, dreadful things.

A bit like leaving jail.

Yes, it was like jail. You couldn’t run away or you’d be in prison. I went back to the farm after I was demobbed, and this guy, Mr Cheesman, who had this beautiful farm in Kent, took me back. We only got piece pay. You got paid by the box of apples. He said he’d give me a little bit of money and showed me this field, where I was supposed to wind these young hop shoots up the wire. I saw this field which seemed to go on forever, and thought to myself, there’s no way I can live like this, I’ll go back to the ballet. Within three or six weeks of being back I was in Australia on the tour. (Below, a typical night in ballet digs for the Royal Ballet Touring Company pictured by Jones, 1962)

This was where you took up photography?

Yes, the first pictures I ever took were in the Empire Theatre, Sydney - a self-portrait. That is the first camera I used, terrible thing (he points at a Ricohflex on the mantelpiece). We were all going to all these exotic places, and all the girls and all the boys were getting cameras and taking pictures to show our parents. You’d get a travel allowance so I bought this camera there in Australia and I didn’t stop after that. We went to New Zealand then, lots of places.

Then in 1960 we went to South Africa. I’ve got pictures upstairs. Not a black person in any of them. Except for one dinner I went to with my first girlfriend, it was all Afrikaans, they hated black people. We practically witnessed the first riots, actually the Sharpeville massacre was on the day we went waterskiing on the Vereeniging river, which was just outside Sharpeville. I’ve still got some photographs somewhere. [The massacre happened on 21 March 1960 - the Royal Ballet spent the day obliviously on the river a few miles nearby and performed in Pietermaritzburg that night.] We didn’t know anything about it. Nobody in the ballet knew what was going on - we were so unpoliticised.

Did you find out on the trip?

No, not until we got back.

[Feeling increasingly disquieted at the disjunct between his closed life and the outside world, the moment that Colin Jones realises would change his life came in the Philippines].

We did some weird tours. We had one that went to Tokyo, Hong Kong and Manila, Philippines. When we got off the plane at Manila, these incredibly wealthy Filipinos were looking after us. On the Sunday we had a day off, and the Marcoses invited us to a party and they served up this meal where there were gigantic cubes of ice inside which were these exotic fish - this bloke would ask you to choose which one, and you’d point at one and they’d cook it.

We had to do this changing of seats during the meal, and I ended up next to Imelda Marcos. I had no idea what to say to her, but we were facing this beautiful bay, and there was this smoke on the horizon. I asked her, what’s that? She said, oh, we’re burning off some of the slums. When we got back to the hotel - we all had chauffeur-driven cars, and I asked my driver to pick me up early in the morning and take me down to where the fires were. I went and saw what was happening, and it was dreadful to see them bulldozing people’s houses and setting light to them. That’s when my life changed. I thought, I don’t want to live and not really know what’s going on in the world. So that’s the moment really when I decided I’d leave the ballet.

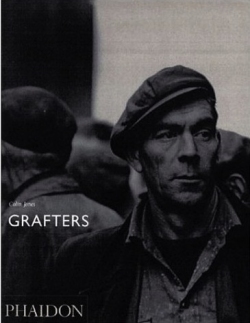

But our last tour was going on to Athens, I think it was, and I decided that when the tour was over I’d print all my pictures and put them into the theatre. I shared a room with Terry Westmoreland, one of the first people to die of Aids in the company. There were what I’d call two sets of people. Kenneth, and Lynn and Ninette de Valois and so on were what I’d call the “Royal Family” and we were the rest. Terry wanted badly to be in the “Royal Family” and he loved my pictures and showed some to Lynn. Some of them are in that Grafters book (2002, pictured left).

But our last tour was going on to Athens, I think it was, and I decided that when the tour was over I’d print all my pictures and put them into the theatre. I shared a room with Terry Westmoreland, one of the first people to die of Aids in the company. There were what I’d call two sets of people. Kenneth, and Lynn and Ninette de Valois and so on were what I’d call the “Royal Family” and we were the rest. Terry wanted badly to be in the “Royal Family” and he loved my pictures and showed some to Lynn. Some of them are in that Grafters book (2002, pictured left).

So it was your photos that made Lynn notice you?

Yeah, yeah. Terry came back and told me, Lynn Seymour has invited you to dinner. We were in Athens. One of those posh rooftop restaurants, and you sit outside on top of the roof. I sat next to her, and that’s how it started. It was some of these pictures from the north-east of England, the slag heaps of Durham. Coal scavengers. Anyway, that’s how I got her attention, and then much to my parents’ disgust I lived with her - because I was actually living at home at the time. The big crunch for us came later, when Kenneth did Romeo and Juliet… We lived in John Cranko’s house, Alderney Street, in the basement. He let us have it.

There were three in the marriage according to Jann Parry's biography of MacMillan.

Kenneth, myself and Lynn, and it got so complicated. He invited me, when Lynn was dancing in New York, he said, I won’t fly, I’m going by boat to New York, will you come with me? So we got on the France, and we were first-class - it was beautiful. But he was there with James Baldwin, the writer, amazingly gay. It was terrible. There were 23 bars on this boat, and they would go to every single one, and drink. Because first-class didn’t pay. So they got so pissed. I didn’t drink so much in those days, but it was all a bit embarrassing.

I imagine Lynn was split in two over it. Her personal life with you, her professional life with Kenneth as his inspiration.

Well, she never really sorted out her personal side. At one time, she really was his inspiration. But you know, they both became pretty alcoholic in Munich. Actually she taught me to drink - in those days, I never had wine. We used to go to all those fancy restaurants, Casserole in the Kings Road. And there were no papparazzi then.

Like that picture you took of her and Nureyev in the pub in the North End Road - they’re just sitting in a pub and none of the other people know who they are (main picture).

Having a beer and a smoke. He didn’t smoke but he drank a lot of vodka. This book on Fonteyn [Meredith Daneman's 2004 biography] is pretty accurate, actually, but they don’t like it at the Opera House. Because she is like a god. They won’t admit she fancied other blokes, like my mate Richard Farley.

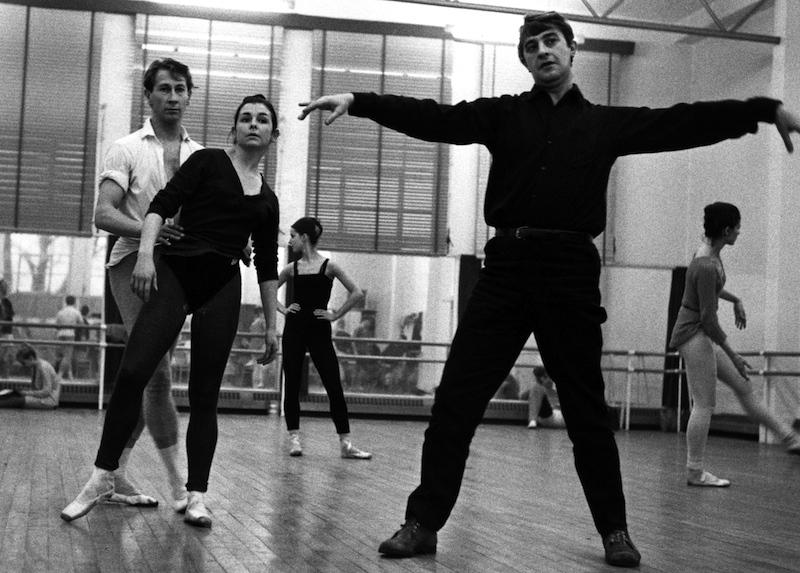

That time, late 50s, early 60s, MacMillan’s creative relationship with Lynn was at its height. (Pictured right by Jones, Kenneth MacMillan rehearsing Lynn Seymour and Desmond Doyle in The Invitation, 1963)

That time, late 50s, early 60s, MacMillan’s creative relationship with Lynn was at its height. (Pictured right by Jones, Kenneth MacMillan rehearsing Lynn Seymour and Desmond Doyle in The Invitation, 1963)

Yes, with [collaborator and designer Nicholas] Georgiadis and everything.

But from your point of view, as husband, you were a spare part?

I was like a spare prick at the wedding! Yes, in a way, but it stayed very friendly in some cases. I mean [he points up to his wall] Georgiadis gave us these designs from Las Hermanas for my wedding to Priscilla. Lynn’s got five, and I’ve got five.

Did you stay friendly with MacMillan?

No. No. Remember, Kenneth was fantastically selfish. He promised Lynn the role of Isadora, but Merle Park did it. Lynn never really recovered from that. That broke her heart, she knew it was really all over with him, as far as creations were concerned.

Were you yourself also aware of being some kind of tangential inspiration to MacMillan? Because what he created in the three of you were a very intense emotional triangle.

Well, he did love tearing women to pieces emotionally. Men, not so much - apart from that last ballet, The Judas Tree, which I think is amazing, though some of the others don’t like it. You know there’s a book come out on history of ballet by this American prat, total rubbish, she just dismissed MacMillan. Can’t see anything beyond America.

Well, he did love tearing women to pieces emotionally. Men, not so much - apart from that last ballet, The Judas Tree, which I think is amazing, though some of the others don’t like it. You know there’s a book come out on history of ballet by this American prat, total rubbish, she just dismissed MacMillan. Can’t see anything beyond America.

I’ll tell you what changed Royal Ballet dancing, that was the first Kirov tour here in 1961. It’s interesting that when Rudy jumped ship in Paris a lot of people were thinking Soloviev was actually better than Nureyev. Soloviev made some amazing pictures. He always did Blue Bird with that girl, Sizova. (Pictured left by Jones, Yuri Soloviev and Alla Sizova performing at Covent Garden on the first Kirov tour, 1961)

Natalia Makarova, who danced with him, told me Soloviev was more limited than Nureyev, though - he was an incredible Blue Bird, he wasn’t a prince.

That’s right. You see, Nureyev had this animal magnetism, I really liked him, he was so funny. We had great fun together. He was a terror. In 1966 Time Life asked me to do a day in the life of Nureyev - that’s one of the pictures from it, in the pub. So I did this day in the life shoot, and one day we organised a trip with Princess Radziwill, who was Jackie Kennedy’s sister. And we were driving to Rickmansworth or something, where there was waterskiing and she wanted to buy a speedboat, top of the range, the Rolls Royce of speedboats - and she was all over him, wouldn’t leave him alone. (The event pictured below by Jones, Lee Radziwill, Nureyev, Radziwill's son, at Rickmansworth, 1965.) And she had her kid with her, which was strange. On the way back, he kept putting his foot up her skirt and she was loving it. Rudy was great fun, very naughty, he used to send these women up, and say, "They think I’m their puppy dog." What did he think about the sacrifice Lynn had made over Romeo?

What did he think about the sacrifice Lynn had made over Romeo?

Well, he was sympathetic, because Kenneth wasn’t mad about Nureyev, or Fonteyn, and when Lynn had to teach them the part made for her, they were all very upset, Kenneth, Georgiadis, Christopher.

But Rudy and Lynn did become very close. Was that during the time of Romeo and Juliet or later?

After it, really. He picked her out - he wanted to dance with her.

Were he and Margot aware that the two of you had lost a child over it?

No. That was Kenneth’s idea. I found out about that when I was in Russia, that she’d had an abortion.

Did you imagine she could have made any other decision?

Well, she did go on to have other children later. But it was Kenneth who did all the arranging of that. He didn’t want to lose her.

What about you? Were you ready to be a father?

No. It wouldn’t matter to me whether I had children or not. I have a daughter, but I’m not a very good family man. I’m selfish. A lot of us are.

You weren’t married long to Lynn.

Not long, only a few years. It took ages to get divorced. When it broke up I think we were all upset. But it didn’t really affect being mates with Rudy and everything. I would still be today. I didn’t go back to the ballet for six or eight years, and it’s only recently that I’ve started to print the ballet pictures, actually.

And then you married Priscilla, and you’ve been together - what, 40 years or something? A lifetime.

Too long!

Thinking about how dance photography has evolved, nowadays there is very much a focus on backstage. In your early days it must have been far rarer. You had the perfect posed performance shots then - now strangely it’s hard to find performance shots of real momentum, with a connection to movement as well as pose. I know dancers are obsessive. In backstage pictures people seem to be seeking the combination of approachability and yet poetic prettiness.

Yeah, pictures like this have to be immaculate [he leafs through some big stage pictures in Alexander Bland's monumental The Royal Ballet: The First Fifty Years]. They are pictures of record. My inspiration was Michael Peto (1908-1970). Have you seen his book on the ballet? He got me into The Observer, he was my inspiration. The Picture Editor at the time was Dennis Hackett. When I went for the interview, he looked at the pictures and said, "I think being a press photographer will be a bit rough for an ex-ballet dancer, don’t ring us, we’ll ring you." And I was dancing somewhere when I got a telegram from The Observer saying could I do six months’ trial as soon as possible? And I’d just signed a contract with the ballet with de Valois and I went and told her I wanted to leave. She said, no problem, even though I’d just signed it.

From what I read about her it appears de Valois was very good about perceiving what people really needed to do with their lives.

She was amazing, yes.

She didn’t like or need jobsworths….

No, no. But photography took a while to come easily. When I went into The Observer - it used to be in Tudor Street - you had to go downstairs and the darkroom was in a sort of prefab, and all the photographers would sit around waiting for the call for a job. There was a lot of favouritism, when I was there, it was Philip Jones-Griffiths, Donald McCullin, David Hearn - they’re all Magnum people now [IB: Philip Jones-Griffiths died 2008], and they resented me because I was an amateur. My very first job was in 1962, you see I was very young.

You went from the bosom of the ballet family to this hostile place.

Yes, they didn’t like me very much.

[Michael Peto’s book, The Dancer’s World, with text by Alexander Bland, came out in 1963, with photographs that brought viewers into a chiaroscuro new contact with the famous dancers, catching them at informal moments or unusual viewpoints. Alexander Bland was the nom de plume of the ballet and culture critic Nigel Gosling and his ballerina wife Maude Lloyd. Gosling used his ballet contacts to gain access to Leningrad for a major coffee table book in 1964 shot by Colin Jones. As well as the stately beauties of Leningrad’s imperial palaces, almost unknown to Western viewers, Jones shot unprecedented pictures of the Kirov dancers in their studios. Pictured right by Jones, the very young Svetlana Efremova and Nikolai Sergeyev at the Kirov Ballet School, 1964]

[Michael Peto’s book, The Dancer’s World, with text by Alexander Bland, came out in 1963, with photographs that brought viewers into a chiaroscuro new contact with the famous dancers, catching them at informal moments or unusual viewpoints. Alexander Bland was the nom de plume of the ballet and culture critic Nigel Gosling and his ballerina wife Maude Lloyd. Gosling used his ballet contacts to gain access to Leningrad for a major coffee table book in 1964 shot by Colin Jones. As well as the stately beauties of Leningrad’s imperial palaces, almost unknown to Western viewers, Jones shot unprecedented pictures of the Kirov dancers in their studios. Pictured right by Jones, the very young Svetlana Efremova and Nikolai Sergeyev at the Kirov Ballet School, 1964]

Would you say that the early Sixties was a time of a sea-change, when dancers were at last showing the kitchen story in the photos, not just performance?

n a way, though in America they were already doing it. But the dancers didn’t always like this type of thing. They don’t understand it. A lot of dancers are thick.

It strikes me that the dancers who move most differently and magically on stage are quite often the ones who can’t easily be photographed, whereas there are others who make beautiful lines and beautiful photographs but are quite dull to watch on stage.

It strikes me that the dancers who move most differently and magically on stage are quite often the ones who can’t easily be photographed, whereas there are others who make beautiful lines and beautiful photographs but are quite dull to watch on stage.

The one I love now is Tamara Rojo, I’ve done her a lot. She’s very bright. She does amazing Juliet. Very much like Lynn would do it. (Pictured left by Jones, young Rojo performing with English National Ballet in the mid-1990s.)

Do you anticipate in your imagination what’s going to happen when you take the picture?

I don’t know why I take pictures or how I take pictures. It’s a complete mystery to me.

There’s so little light in some of these. One thing interesting about this style of photographing is black and white, and the texture is powdery, almost, it has a theatricality...

… because it’s not true, that’s why.

I meant, this is beautiful, it's soft, wafting shapes, not lines and graphics. But it’s also neither a performance nor a kitchen story. So you as a dancer must have been torn by the requirements of other dancers to show perfect fifth or your desire to do something more imaginative.

To get that type of picture you have to follow the music. If you do that, at some time you’ll get the perfect shot where the feet and everything are right. But a lot of the time I don’t. In the Leningrad book, which is one where I lost or destroyed a lot of the negatives, the dancers used to come on stage and pose for the press.

You don’t have a motordrive, so the key to a shot is listening...?

Yes, if you get the music on the right beat, the dancer should be there too. So you go with the music. But in something like Kenneth's The Invitation I never understood the music and I’d count. Lots of dancers count.

What about Fonteyn? How was she about photos?

I don’t know. We used to have to stand up when she came into class.

So you never got close, despite your friendship with Rudy?

No.

How did she feel about Lynn?

They didn’t get on, did they? And Lynn was a bit upset about having to teach Fonteyn her Juliet role...

One thing I love about Seymour’s face in these pictures is the roundness of her cheek.

She had all these weight problems, you know, she was always going on about it. But Lynn was unusual as she didn't mind being photographed at all.

What was the hardest role you yourself danced?

The Ivans, I suppose, in Sleeping Beauty. Which they don’t do now.

When you became a photographer, you still kept the ballet links, you worked with Nigel Gosling, the critic, on the Leningrad book.

Maude and Nigel befriended me, like they befriended Rudy, and everybody. That’s where Lynn went when she left me, she went to stay with them. I had a row with him in the end. But the Leningrad book with Nigel got reviewed in Time Life and it upset Russians and it’s an amazing saga. When I got back, someone got in touch with me in London. He had my phone number - how did he get that? He rang up and said he was from Leningrad, he was with Intourist - who were the KGB. He said he would like to meet me. "Meet me at Fulham Broadway on platform something or other, I’ll have the Telegraph under my arm." We went to a café, and he said, he’d been working for InTourist etc, and he wanted me to take some pictures. I said, what of? He said, Jodrell Bank.

I told the Observer picture editor who said, don’t do it. MI5 and MI6 will let you go along with it then they’ll do you for spying. These people are ruthless. And he was absolutely right. They got very upset that I wouldn’t take pictures of Jodrell Bank. But that’s how they start to trap you. The first time I’d gone to Leningrad was with the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Julie Christie.

How different were actresses and dancers to photograph?

The worst people to photograph are politicians - they’re the most conceited. Pop stars, sometimes. But politicians I hated. I think with actors it is more about the head that you're focusing on, the body doesn’t seem to matter so much. Like Dirk Bogarde, for instance - he could only be photographed one side! The other one was that great friend of Lynn’s, Fenella Fielding - who would get everything booked in a restaurant and then go in and say, "Oh, I can’t sit here, the lighting is all wrong." We would go to Stratford quite a lot and I was asked by Nova magazine to do a profile on the Royal Shakespeare Company. I knew Michael Williams, who was married to Judi Dench; we used to get so pissed in the Dirty Duck, this pub just across the road from the stage door. It was run by this amazing woman - you know, the hours of opening in those days were very strict, but all the actors would get into the pub and she’d lock the door, and get out the Champagne and Guinness. Great time I had there, we all did.

How different was it when you started shooting pop stars like The Who in the '60s?

I shot pop stars like I’d shoot the ballet. I don’t like them, I’m not a pop photographer, though I’ve done quite a bit of it. I got on well with Pete Townsend, he used to come and stay at the flat in Baron’s Court.

They’re very reliant on photographers for their image, aren't they?

Yes, they need someone. He asked me to go on their first American tour but I turned it down, because there was too much drinking. When I first met them, I went into this club in Manchester, and the place was just filled with Mateus Rosé bottles, they used to drink gallons of it, pop pills, and not turn up for the second show. Terrible. And always fighting - they’d fight on the bloody train. No discipline. So to go on a tour with them I’d have ended up a drug addict or an alcoholic. Which they all did. You see, Pete Townsend did, and Eric Clapton. Though I like Eric very much - a very nice bloke.

People think of dancers and miners are polar opposites, but I’d think pop stars and miners might be more opposite. One lot unimaginably hardworking, the other lot mainly lucky.

I got very criticised for my book Grafters for putting coal-miners in the same class as dancers.

Why did you do it?

Because they do the same type of physical work: they live in close-knit communities - mining villages are the same as dance companies. And down the pit miners help each other, even though they might be enemies. Down there, even if they don’t talk above, they’re all in it together, in the same boat - there’s a kind of camaraderie. It seemed to me that in the ballet world it was the same.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Add comment