The Artist's Wife review - uninspired portrait of dementia in the Hamptons | reviews, news & interviews

The Artist's Wife review - uninspired portrait of dementia in the Hamptons

The Artist's Wife review - uninspired portrait of dementia in the Hamptons

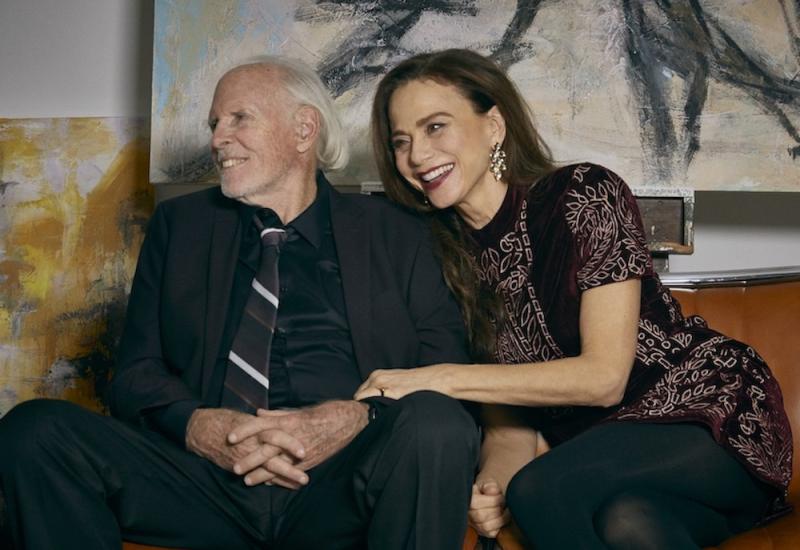

An artist's wife rediscovers her own creativity: Lena Olin and Bruce Dern star

“The only child I’ve ever had is you,” the artist’s wife (Lena Olin), spits at the artist, her considerably older husband (Bruce Dern), who retorts, “That was your goddamn choice so don’t blame it on me.”

Although the setting – a wintery East Hampton – is gorgeous, this portrait of Richard Smythson, a celebrated abstract artist just diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and his equally talented wife Claire, who gave up her own painting career in favour of his, never veers far from a well worn path.

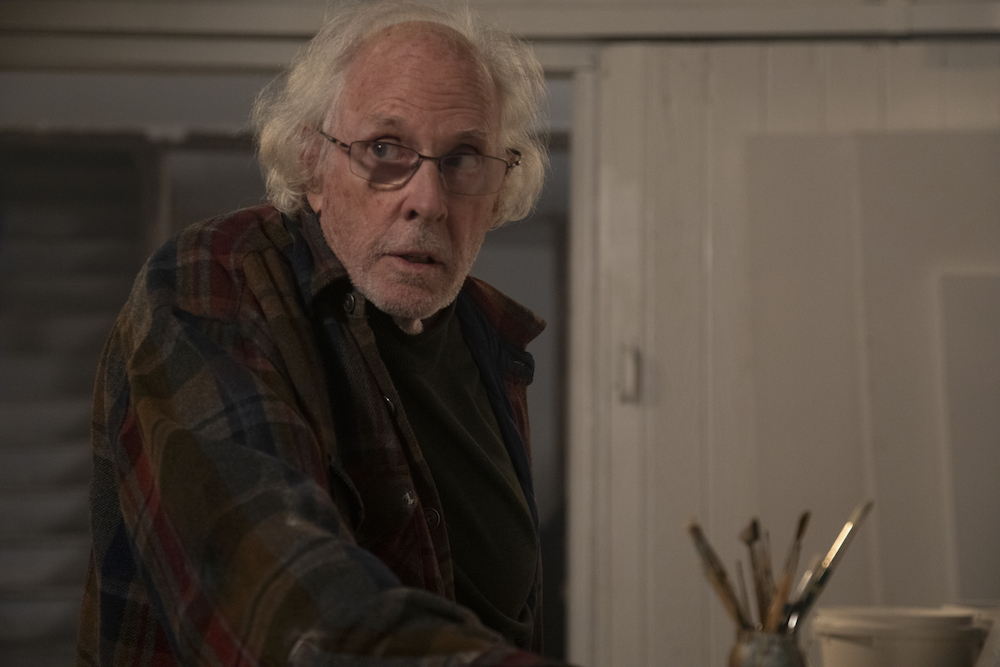

It doesn’t bear comparison with Nebraska, where Bruce Dern played another senile old chap so magnificently. Still, it raises questions about what’s normal behaviour and what isn’t, especially for a genius, and how to tell when a cantankerous old bastard turns into a recognisably demented one. And how, when that genius husband is lost to dementia, his wife may find herself again.

But none of these issues is addressed very compellingly by director and co-writer Tom Dolby, whose own father, Ray Dolby, the inventor of Dolby sound, had Alzheimer’s. You never get much sense of what the relationship was like before Richard became ill so it’s hard to mourn its loss, unlike in other films about dementia, such as Away from Her, Still Alice or Viggo Mortensen’s recent Falling, which is, like The Artist’s Wife, rooted in personal experience.

Claire and Richard live in splendour – privilege oozes throughout the film - in a black slab of a modernist house with huge windows. Their marble-counter-topped kitchen is lustrous, their fridge, stacked with perfect produce in rows of plastic containers, is of a pristine quality rarely seen in real life. Even his studio, where he’s trying in vain to produce works for a much anticipated show (his agent, played by Tonya Pinkins, keeps asking awkward questions about progress), looks remarkably spick and span, which contributes to the shallow feel that pervades. Richard is a bully and extremely rude to his young students, smashing a poor sucker’s canvas and asking him to repeat, “My painting is a piece of shit and doesn’t deserve to exist,” but this may be par for the course for all we know. Claire and Richard seem close, even jolly, though chemistry is lacking – or is that because he’s forgotten his Viagra?

Richard is a bully and extremely rude to his young students, smashing a poor sucker’s canvas and asking him to repeat, “My painting is a piece of shit and doesn’t deserve to exist,” but this may be par for the course for all we know. Claire and Richard seem close, even jolly, though chemistry is lacking – or is that because he’s forgotten his Viagra?

Claire spends a lot of time staring wistfully out at the snow and sipping cup after cup of coffee from a fancy machine (though a preview of an old friend’s show at the New Museum provides a distraction, with Stephanie Powers of Hart to Hart in a surprise, Italian-accented cameo). Richard buys a $94,000 clock ("I hope we can return it," mutters Claire, rather mildly under the circumstances) and pours orange juice over his Grape-Nuts.

When she gets the diagnosis from a sympathetic doctor who seems more like a friend (we don’t see Richard’s reaction) she’s in denial, and we feel for her. Lena Olin’s face is always expressive and volatile. “Does everyone have to be normal all the time?” she asks tearfully. When getting his new prescription filled she’s oddly flummoxed by the chip-and-pin card machine, then gets belligerent with an employee at the supermarket after he catches her eating an energy bar before she pays for it. Who’s acting forgetful now?

Don’t do this alone, the doctor tells her. Get the family on board. What family? wonders Claire, as she runs despairingly along a beautiful empty beach. Ah yes – Richard’s bitterly estranged daughter Angela (Juliet Rylance; McMafia, Perry Mason), recently divorced from her wife. Stressed-out Angela lives with their son Gogo (Ravi Cabot-Conyers) in a luxury New York apartment building, complete with doorman and handsome manny/musician named Danny (Avan Jogia).

What she does with these paintings forms the film’s rather lacklustre denouement. “It’s very hard to look inside and paint what’s all gone,” complains Richard, as he stares at a blank canvas. Dolby, who is also a novelist and producer, has said that he sees his film as a tribute to caregivers as well as to female artists who have supported their famous husbands – Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Dora Maar - but this ambition may be a bit of a stretch. Claire, it seems, has just started to look inside again, and likes what she sees, but it’s hard to muster up much excitement about her reclaiming her future as an artist.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Friendship review - toxic buddy alert

Dark comedy stars Tim Robinson as a social misfit with cringe benefits

Friendship review - toxic buddy alert

Dark comedy stars Tim Robinson as a social misfit with cringe benefits

S/HE IS STILL HER/E - The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary review - a shapeshifting open window onto a counter-cultural radical

Intimate portrait of the Throbbing Gristle & Psychic TV antagonist

S/HE IS STILL HER/E - The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary review - a shapeshifting open window onto a counter-cultural radical

Intimate portrait of the Throbbing Gristle & Psychic TV antagonist

Blu-ray: Heart of Stone

Deliciously dark fairy tale from post-war Eastern Europe

Blu-ray: Heart of Stone

Deliciously dark fairy tale from post-war Eastern Europe

Superman review - America's ultimate immigrant

James Gunn's over-stuffed reboot stutters towards wonder

Superman review - America's ultimate immigrant

James Gunn's over-stuffed reboot stutters towards wonder

The Other Way Around review - teasing Spanish study of a breakup with unexpected depth

Jonás Trueba's film holds the romcom up to the light for playful scrutiny

The Other Way Around review - teasing Spanish study of a breakup with unexpected depth

Jonás Trueba's film holds the romcom up to the light for playful scrutiny

The Road to Patagonia review - journey to the end of the world

In search of love and the meaning of life on the boho surf trail

The Road to Patagonia review - journey to the end of the world

In search of love and the meaning of life on the boho surf trail

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Emma Mackey on 'Hot Milk' and life education

The Anglo-French star of 'Sex Education' talks about her new film’s turbulent mother-daughter bind

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Emma Mackey on 'Hot Milk' and life education

The Anglo-French star of 'Sex Education' talks about her new film’s turbulent mother-daughter bind

Blu-ray: A Hard Day's Night

The 'Citizen Kane' of jukebox musicals? Richard Lester's film captures Beatlemania in full flight

Blu-ray: A Hard Day's Night

The 'Citizen Kane' of jukebox musicals? Richard Lester's film captures Beatlemania in full flight

Hot Milk review - a mother of a problem

Emma Mackey shines as a daughter drawn to the deep end of a family trauma

Hot Milk review - a mother of a problem

Emma Mackey shines as a daughter drawn to the deep end of a family trauma

The Shrouds review - he wouldn't let it lie

More from the gruesome internal affairs department of David Cronenberg

The Shrouds review - he wouldn't let it lie

More from the gruesome internal affairs department of David Cronenberg

Jurassic World Rebirth review - prehistoric franchise gets a new lease of life

Scarlett Johansson shines in roller-coaster dino-romp

Jurassic World Rebirth review - prehistoric franchise gets a new lease of life

Scarlett Johansson shines in roller-coaster dino-romp

Add comment