Zalika Reid-Benta: Frying Plantain review - tales of growing up young, black and female in Toronto | reviews, news & interviews

Zalika Reid-Benta: Frying Plantain review - tales of growing up young, black and female in Toronto

Zalika Reid-Benta: Frying Plantain review - tales of growing up young, black and female in Toronto

A writer-in-the-making studies the art of not making a scene

It is as unsurprising as it is vital that a spotlight has been thrown on writing by people of colour this year. It is unsurprising, too – looking at bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic since June – that most of that light is being shed on particular kinds of writing by people of colour: stories and histories of struggle and suffering. These books, non-fiction and fiction alike, are typically said to “bear witness” – as they should.

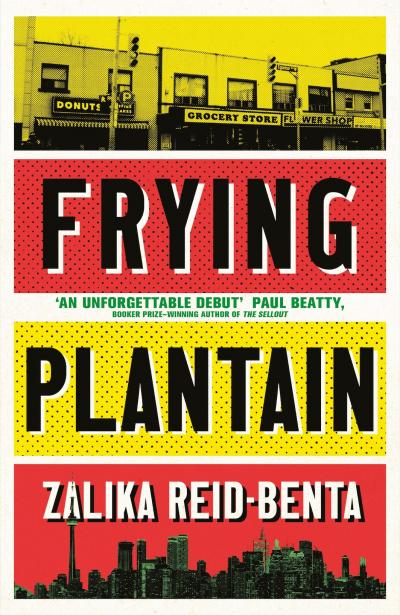

In the case of Frying Plantain, the debut set of linked semi-autobiographical stories from Zalika Reid-Benta, we follow a Black person learning how to be. This is the coming of age story of Kara, an underprivileged Canadian girl with Jamaican heritage living across Toronto, from her early school days through to university. Her experience is hedged with seemingly endless dangers and fears: of being looked at by the “storefront boys” in Eglinton West (known as Little Jamaica); falling foul of the eagle eyes and high morals of the “faith community” women; being caught in yet another of her family’s earth-shattering arguments; being considered too “stush” by the neighbourhood kids or falling out of favour with her white school friends; and of her mother Eloise finding out about her boyfriend, that she skipped school (once) or drank (once).

Reid-Benta attests to all this, and there is undoubtedly a sociopolitical undertow to the stories she tells (how could there not be). But they unfold without any of the potentially forbidding weight the “bearing witness” cliché implies. There is nothing heavy here, nothing pregnant (much to the relief of Kara’s mother). The writing may not always be sweet with stinging sections of dialogue, but it is almost always impossibly light: airy, transparent, fluent – as Kara longs to be in the patois of the kids who have just come from the “the Islands”.

Such fluency betrays Reid-Benta’s real interests in her writing: not necessarily in the technicolour play and texture of the written word, but in people: their gestures, looks and physicality. As ever, it is tempting to find some sort of guiding, overarching metaphor in the book’s title, but as the book goes on, it becomes clear that it is descriptive, above all else above. The final and longest story is entitled “Frying Plantain”: memories of Kara’s earliest years living in her grandmother’s basement before her father disappeared intermingle with a strained courtesy visit to the house and its bad memories in the present. Reluctantly and quietly, Kara marvels at her grandmother’s handling of plantain:

“The way she peels plantain has always impressed me. The blade just slides through like nothing; there’s no sign of effort or struggle. I don’t see the blade tug at the toughness of the skin like when I do it. This looks easy; this looks like the plantain is undressing itself.”

Any fans of the programme Chef’s Table will be seeing visions: the close-up, the slow-mo. Of course, there is depth and history to this skill – knowledge passed on from generation to generation – but in the moment, we are taken in by the surface, the display. It is presented as if through a camera lens, and Kara is almost always in the director’s chair. A few of the stories switch to the third person such as the entertaining “Inspection”, where we see Kara keening for a return to her old neighbourhood, where no one holds their tongue or hides their looks – but even then, we rarely see Kara acting out herself. This is a coming-of-age story mostly populated by other people.

It comes as no surprise to learn that Reid-Benta is a cinema studies graduate, a subject we are told Kara also opts for. Reid-Benta has a playwright or screenwriter’s eye for the way bodies operate in space, and how power plays out among them. “Fiah Kitty” is a beautiful exercise in turning up the heat: Kara’s mother stays unusually tight-lipped and poker-faced at Nana’s at Christmas, her few, forced kind words only helping to ratchet up the tension. Even when characters are not speaking, or otherwise refusing to be civil to one another, like the grandparents in “Standoff”, you can hear drama sizzling away. (Maybe there is something in the title after all.)

In the middle of a row, Kara’s grandpa, an unreformed philanderer who spends half of his time out of the house, makes a show of watching TV in the living room – which is a habit picked up and displayed by Kara’s mother – and “an exhibition of his moth-eaten socks” as an affront to housewifely responsibilities. As if picking up on the cue, Nana shirks them all, refusing to dress up, clean or cook, although she still makes plenty of noise in the kitchen. These actions within the confines of the home say all we need to know about them, their unshiftable (very Jamaican) pride and a few decades’ worth of passive-aggressive behaviour. The way Kara navigates the spaces between the two – she has to “squeeze past the rounded edge” of the dining table that separates the living room and kitchen to avoid getting caught in the silent crossfire – says all we need to know about her relationship with both.

It is part of the strategy of the book for us to read between the lines. As a novel told in short stories, it is steadily chronological, but with jump cuts. We learn about the big events – another murderous row, a move, a fallout, a car accident – as if in passing. You could almost say the stories themselves are the sort of things that happen in between the acts: they’re the aftermath, the leftovers. Supported by that weightless style, Frying Plantain is almost wilfully undramatic. Kara is always biting her tongue, avoiding confrontation, cooling things down, keeping the peace – the peace that Kara realises “could only exist in this family when we lied about everything, at least to each other.” She has a storyteller’s sensibilities: her increasingly tall tale about seeing a pig’s head during a family trip to Jamaica rings alarm bells at school, and she can’t help but get invested in the messy lives of the couple next door whose real-life soap opera she hears through the thin walls of their downtown Toronto apartment. But really, her art is the art of not making a scene. As she states at one point, “my mother made scenes—I didn’t”.

That art, at times a survival skill, is like an extension of the way the young Kara used to “play with porcelain figurines” on her grandmother’s dresser – figurines that Kara’s dad would desperately try to return to their original positions to avoid complaints from the tirelessly fastidious Nana. Kara puts on “productions”, staging “dramatic arguments and theatrical reunions between the milkmaids and young lads”. In these stories, she graduates from those silent figures to the living, breathing, occasionally dishonest, occasionally racist, occasionally cantankerous, and occasionally “facety” people around her. But, in the end, it is what these people do – how they stand, sit, walk, dress, look, pose – rather than what they say, that really grabs the attention of Reid-Benta, as well as our own.

- Frying Plantain by Zalika Reid-Benta (Dialogue Books, £14.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Add comment