Ailish Tynan, Iain Burnside/Allan Clayton, James Baillieu, Wigmore Hall online/BBC Radio 3 review – alone together | reviews, news & interviews

Ailish Tynan, Iain Burnside/Allan Clayton, James Baillieu, Wigmore Hall online/BBC Radio 3 review – alone together

Ailish Tynan, Iain Burnside/Allan Clayton, James Baillieu, Wigmore Hall online/BBC Radio 3 review – alone together

Fine singing and dramatic flair in hours of sweet solitude

Loneliness haunts the solo song – not simply all those solitary wanderers and defiant wayfarers of the Lied tradition, but the forsaken lovers and questing pilgrims who fill the folk-song repertoire of many lands.

Yet both singers reached out to touch hearers so directly that the pin-drop silence that greeted the end of each item, and of each hour, felt unusually bleak and disturbing. Tynan and Clayton both generously shared songs of joy as well as pain – and made us realise the essential part that a live audience plays in closing the journey of concerts such as these. In the repopulated musical future (should it come to pass), I’ll be less keen to whinge about ill-timed splutterers and premature applauders, who at least remind us that they’re present.

In the absence of a visible public, both singers regaled their invisible one with interpretations packed with dramatic flair on top of vocal prowess. Ailish Tynan began with Grieg’s Op. 48 Six Songs from German poems, her voice both robust and expressive, and often blooming into genuine grandeur in its middle range. In its emotional compass, the Grieg sequence spans the titillating mischief of “Lauf der Welt” ("The way of the world") and the almost Mahlerian elegiac fervour of the final number, “Ein Traum” ("A dream"). Tynan showed both spirit and serenity in abundance, articulating crisply in the busier passages yet still managing to float the top notes of “Ein Traum” out into the Wigmore void with a show-stopping authority.

After Grieg’s easy-access lyricism, the more introspective subtleties of Hugo Wolf’s Goethe settings required a shift of angle. Her “Ganymed” had a lovely bloom and sheen, ripening into finely controlled crescendos. As for “Kennst du das Land” ("Do you know the land"), Tynan embraced its yearning and nostalgia with an operatic warmth and depth. For anyone longing for the land where the lemons blossom this summer, her version of Mignon’s song all but crossed the Alps by itself. Iain Burnside, meanwhile, supplied a second voice of matching eloquence as he made the most of Wolf’s post-Wagnerian sensuousness, somehow lush and yet chaste.  With Tynan and Burnside as their advocates, the four settings of traditional Irish songs by Herbert Hughes that followed didn’t sound like such a drastic change of gear. The Debussy-influenced Hughes evidently had one ear on the salon and another on the tavern. If his “The Leprechaun” gave Tynan a showcase for some enjoyably corny shamrockry, then “The Gartan Mother’s Lullaby” balanced glorious sweetness with a subdued tension in the piano part that complicates the mood. Tynan’s pair of “Memories” by Charles Ives likewise offset one “very pleasant” comic patter song about opera-house curtain-up buzz (“a feeling of expectancy, a certain kind of ecstasy”) with the “rather sad” comedown of an uncle's nostalgic tune (“it is tattered, it is torn, it shows sign of being worn”). As Clayton also would later in the week, Tynan properly acted every song as if a packed, cheering stadium hung on her every breath.

With Tynan and Burnside as their advocates, the four settings of traditional Irish songs by Herbert Hughes that followed didn’t sound like such a drastic change of gear. The Debussy-influenced Hughes evidently had one ear on the salon and another on the tavern. If his “The Leprechaun” gave Tynan a showcase for some enjoyably corny shamrockry, then “The Gartan Mother’s Lullaby” balanced glorious sweetness with a subdued tension in the piano part that complicates the mood. Tynan’s pair of “Memories” by Charles Ives likewise offset one “very pleasant” comic patter song about opera-house curtain-up buzz (“a feeling of expectancy, a certain kind of ecstasy”) with the “rather sad” comedown of an uncle's nostalgic tune (“it is tattered, it is torn, it shows sign of being worn”). As Clayton also would later in the week, Tynan properly acted every song as if a packed, cheering stadium hung on her every breath.

After the sardonic, Sondheim-like ambiguities of “Pregnant” by Lilly Larsen, Tynan’s “Over the Rainbow” far surpassed mere Judy Garland tribute-act level to channel some of the deferred hopes of these past strange months. But, BBC and Wigmore, why give no credit for Yip Harburg’s lyrics as well as Harold Arlen’s music? Tynan throughout had offered hints and glimpses of her opera-sized dramatic gift, and her encore of “Si, mi chiamano Mimi” from La Bohème briefly let it bloom. This season, she would have sung that role at Grange Park Opera. Another treat, let’s hope, in store for 2021.  Allan Clayton, too, began in the heartland of the German-language art song before moving into the border territory where fragments of traditional music meets conservatoire sophistication. Schumann’s 12 Kerner Lieder from 1840, his prolific “year of song”, set poems (by Justinus Kerner) that demand from the singer a bulging quiver of Romantic postures and gestures. Clayton covered very inch of this enchanted (and haunted) forest in style, from the declamatory traveller’s optimism of “Wanderlied” through the tipsy sways and lurches of “Auf das Trinkglas eines verstorbenen Freundes” ("To the drinking glass of a departed friend") to the full-strength ardour and desolation of “Stille Tränen” ("Silent tears").

Allan Clayton, too, began in the heartland of the German-language art song before moving into the border territory where fragments of traditional music meets conservatoire sophistication. Schumann’s 12 Kerner Lieder from 1840, his prolific “year of song”, set poems (by Justinus Kerner) that demand from the singer a bulging quiver of Romantic postures and gestures. Clayton covered very inch of this enchanted (and haunted) forest in style, from the declamatory traveller’s optimism of “Wanderlied” through the tipsy sways and lurches of “Auf das Trinkglas eines verstorbenen Freundes” ("To the drinking glass of a departed friend") to the full-strength ardour and desolation of “Stille Tränen” ("Silent tears").

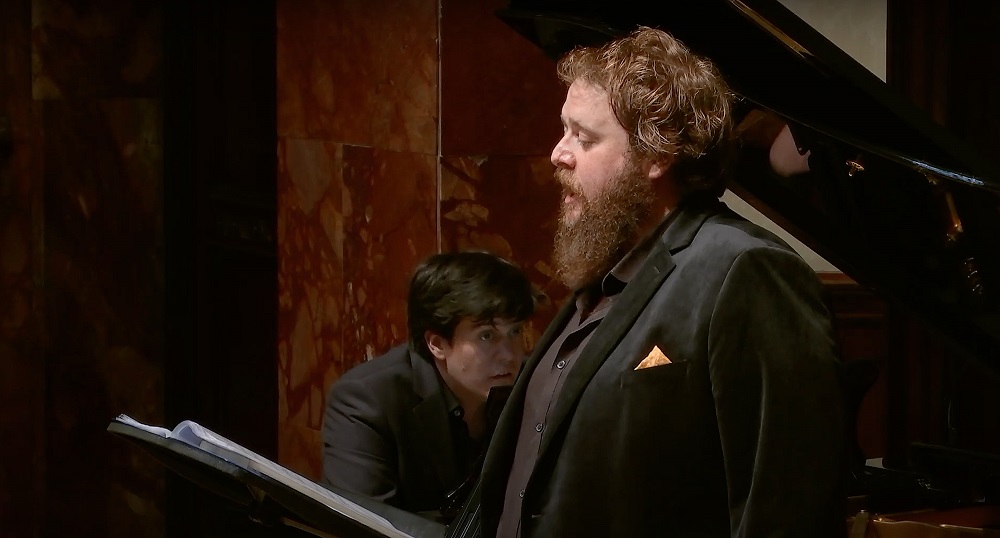

Clayton embodies as much as he interprets, enriching every twist of timbre and colour with expressions that ground the music’s passions in the here-and-now of performance. He articulates beautifully, and never sacrifices clarity for brute force – although his hall-filling fortissimo passages packed quite a punch. James Baillieu (pictured above with Clayton) proved an admirable accomplice, gently traversing the ever-changing scenery of piano moods that can take in the folksiness of “Erstes Grün” ("First green"), the wistful chromaticism of “Stille Liebe” ("Silent love"), and the sparse, eerie leave-taking of “Alte Laute” ("Sounds from the past).  The pair then moved to England, as they contrasted the neo-Tudor cadences of Vaughan Williams’s “Orpheus with his Lute” (from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII) with the harsher, more sardonic tonalities of Frank Bridge (“Journey’s End”) and the shadowed nostalgia – tinged with cynicism – of Roger Quilter’s “Go, lovely rose”. To round off his hour, three Britten settings gave Clayton the chance to prove how much versatile work the “folk song” label does in such endlessly creative hands. If “The Plough Boy” delivers a knowing and satirical slice of Georgian mock-pastoral, then “I wonder as I wander” – based on an Appalachian hymn – sent us back into a lonely, almost archaic, landscape of ritual balladry.

The pair then moved to England, as they contrasted the neo-Tudor cadences of Vaughan Williams’s “Orpheus with his Lute” (from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII) with the harsher, more sardonic tonalities of Frank Bridge (“Journey’s End”) and the shadowed nostalgia – tinged with cynicism – of Roger Quilter’s “Go, lovely rose”. To round off his hour, three Britten settings gave Clayton the chance to prove how much versatile work the “folk song” label does in such endlessly creative hands. If “The Plough Boy” delivers a knowing and satirical slice of Georgian mock-pastoral, then “I wonder as I wander” – based on an Appalachian hymn – sent us back into a lonely, almost archaic, landscape of ritual balladry.

The ringing, prophetic splendour of the voice and the stark austerity of the piano threw out their compelling appeal for divine absolution to a (physical) audience that wasn’t there. But solitude can bring serenity, and their encore – Liszt’s, rather than Schubert’s, setting of Goethe’s second "Wandrers Nachtlied" ("Wanderer's nightsong") – guided us gorgeously to rest with an impassioned tranquillity. As it closed, Clayton’s tenor climbed impossibly high to vanish into silence above the darkened mountain peaks. “In sweet music is such art,” as Shakespeare’s Queen Katharine sings in “Orpheus…”, “Killing care and grief of heart”. The Wigmore’s hours of solitary song have certainly helped to do that.

- Both concerts can be seen on the Wigmore Hall website and heard on BBC Radio 3; the series continues on both

- More classical reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Add comment