Jung Chang: Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister review – China's century in three women's lives | reviews, news & interviews

Jung Chang: Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister review – China's century in three women's lives

Jung Chang: Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister review – China's century in three women's lives

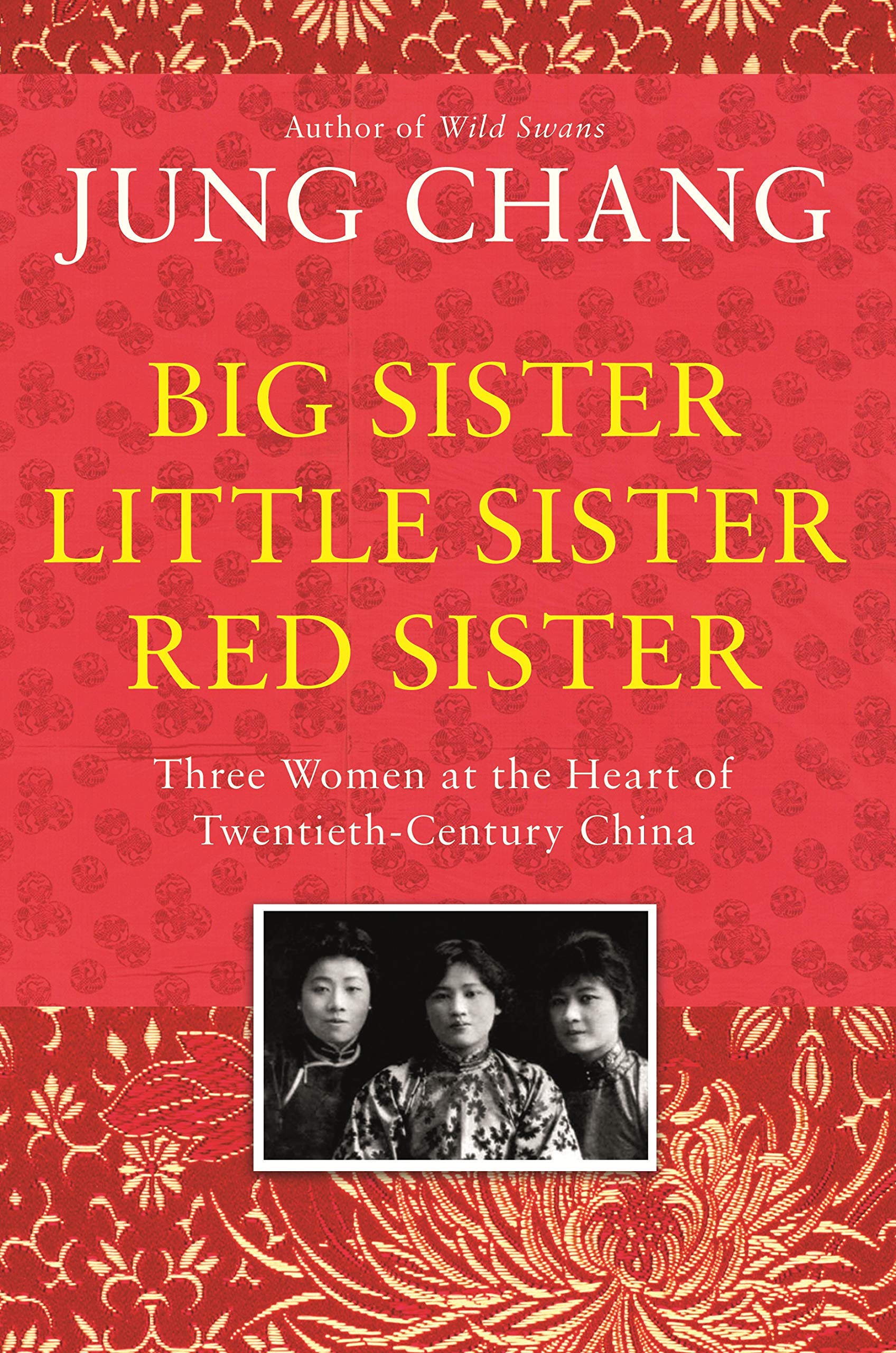

Action-packed group portrait of the 'fairy-tale' sisters who helped shape a nation

In 1930, a couple of romantically involved Chinese expats in Berlin – both revolutionaries in their own way – went on a farewell date. One of them, Deng Yan-da, was due to return home to continue his clandestine political work. The pair saw Marlene Dietrich smoulder through The Blue Angel. Two decades later, Deng’s former partner, Soong Ching-ling, asked a German friend to send a disc of Marlene singing “Falling in Love Again” to her in China.

The siblings who form the subjects of Jung Chang’s three-panelled portrait enjoyed privileges and opportunities beyond the dreams of almost all Chinese women. Yet the lingering impression left by this biographical triptych, crowded almost to the point of surfeit with drama, colour and character, is that the Soong sisters of Shanghai remained prisoners of a kind as well. Allied not just by marriage, but by commitment and principle, to the mightiest men and movements of their age, all became powers not so much behind as beside the throne – a high-profile “fairy-tale” trio viewed either as saintly godmothers of change or wicked manipulators who shaped China to their selfish ends. Chang’s narrative emphasises their agency, and their authority. One of the sister’s political interventions, we are told, “saved her country as well as her husband”. However, both as women and as elite actors in a fast-moving history beyond their control, we seem to see them through the bars of a gilded and luxurious cage.

As in her bestselling saga Wild Swans, Chang uses the fate of one family as a prism to illuminate many facets of the modern Chinese past as upheaval succeeds upheaval throughout the 20th-century. Ei-ling Soong (her given name means “Kind Age”) was born in 1889; Ching-ling (“Glorious Age”) in 1893, and May-ling (“Beautiful Age”) in 1898. Their father, businessman and political operator Soong Charlie, had been educated by Methodists in the US and spoke English better than Chinese; he had married Ni Kwei-tseng, a daughter of “China’s most illustrious Christian clan”. All three studied at Wesleyan University in Georgia. The sisters’ slangy, sharp and revealing English-language letters light up this book. Western, Christian and cosmopolitan connections moulded the Soong girls’ lives (there were also three brothers). In later life, Ei-ling and May-ling became “virtually New Yorkers” – the city they loved most. As happened with other post-colonial elites across the world, the Soongs came to occupy leading roles in a country about whose everyday life they knew, at first hand, remarkably little.

“Red Sister” Ching-ling married the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, the so-called “Father of China”. In her notably hostile – and carefully documented – portrait, Chang undermines the heroic myth of his role in the early years of the Republic after the Qing Dynasty fell (in 1912). For her, Sun’s unscrupulous manoeuvres “unleashed decades of bloody internal strife”. Yet his timely alliance with Soviet Russia and protection of the fledgling Communist Party – not to mention Ching-ling’s later devotion to its cause – secured Sun’s place in the Mao-era pantheon of heroes.

“Big Sister” Ei-ling, “the most brilliant mind in the family” (according to May-ling), grew into a “paragon of self-control”, a strong-minded and decisive businesswoman. She married the entrepreneur HH Kung, who would become prime minister and finance minister in the Nationalist governments of Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang – the “consummate schemer” of a Generalissimo who seized power in 1928, fled from Mao's forces to Taiwan in 1949, and died in 1975 – became husband to the charming, mercurial and “tigerishly self-willed” May-ling. While most of “the extended Soong family” flourished at the heart of Chiang’s regime, Ching-ling acted as one of Mao’s most energetic and resourceful fellow-travellers (her Party membership, however, stayed a secret).

The Soong sisters not only enjoy ringside seats as civil strife and then world war engulf China. Sometimes, they help direct the action themselves: as Chiang trashes the democracy of the early Republic en route to his “unapologetic dictatorship”, as the Japanese brutally invade Manchuria and then torment much of China, and as Mao recovers from defeat to begin the Communists’ “Long March” to power. Chang’s insistence on viewing key events through a family lens can feel strained – as when she almost ascribes Mao’s Long March itself to May-ling’s efforts to broker the release of Chiang’s son Ching-kuo (from his first marriage) out of captivity by a Northern warlord. She makes much of May-ling’s and Ching-ling’s childlessness as the force behind their respective “mother of the nation” poses.

The Soong sisters not only enjoy ringside seats as civil strife and then world war engulf China. Sometimes, they help direct the action themselves: as Chiang trashes the democracy of the early Republic en route to his “unapologetic dictatorship”, as the Japanese brutally invade Manchuria and then torment much of China, and as Mao recovers from defeat to begin the Communists’ “Long March” to power. Chang’s insistence on viewing key events through a family lens can feel strained – as when she almost ascribes Mao’s Long March itself to May-ling’s efforts to broker the release of Chiang’s son Ching-kuo (from his first marriage) out of captivity by a Northern warlord. She makes much of May-ling’s and Ching-ling’s childlessness as the force behind their respective “mother of the nation” poses.

The Second World War convulses the nation, Mao triumphs in the aftermath, and Big and Little Sisters retreat to Taiwan with Chiang (prior to their long stretches in New York). Chang’s pages seethe and roil with incident. It can be hard to keep up. Moreover, for all the fascination of the women’s lives, the reader seldom warms to them. The exigencies of survival had, unavoidably, thickened their skins.

The “colossal corruption” of HH Kung and Ei-ling, first in their Shanghai fiefdom and then on Taiwan, led President Harry Truman to denounce the Soong and Kung clans as “all thieves, every damn one of them”. May-ling, as the revered “Madame Chiang Kai-shek”, turned into a global byword for monarchical extravagance, although Chang underlines her personal kindness. As for Ching-ling, during the war US General Joseph Stilwell had found her “the most simpatico of the three women, and probably the deepest”. Later, as Mao’s honorary right-hand woman (though deprived of actual power): “Politically, she was priceless” to the Communist regime. Sun Yat-sen’s widow, who informally adopted two wayward children, lived on as a “pure decoration” for the Party through the darkest hours of Mao’s Great Famine and the Cultural Revolution. She might write private letters “frank with anger and revulsion at the cruelty and atrocities all around”; but, in public, “she did not protest”.

Chang’s focus on these three extraordinary lives repeats a formula that has served her well. It allows her to stride over a vast, ceaselessly dramatic century of world-shaking events (May-ling addressed the US Congress, “energetically and impressively” in 1995, and, amazingly, only died – aged 105 – in 2003.) Yet her heart, I regularly felt, lay not with these charismatic if armour-plated women but with the lost hopes of liberal democracy in China: with the ideals of Deng Yan-da; with the fragile Republic of the 1920s, its free institutions and “tolerance of dissent”; finally, with the democratic Taiwan built after Chiang Kai-shek and the Soongs had lost their iron grip on the island. The three sisters emerge as divas, as icons, as legends – but not quite as the heroines of this epic tale.

- Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China by Jung Chang (Jonathan Cape, £25)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment