Prince Albert: A Victorian Hero Revealed, Channel 4 review - dramatic documentary filled with intelligent detail | reviews, news & interviews

Prince Albert: A Victorian Hero Revealed, Channel 4 review - dramatic documentary filled with intelligent detail

Prince Albert: A Victorian Hero Revealed, Channel 4 review - dramatic documentary filled with intelligent detail

The privileged prince who was simultaneously an oppressed outsider

It may sound perverse to say it, but Albert was the perfect twenty-first century prince. Thrust into the heart of the British monarchy he was simultaneously an oppressed outsider who – despite his reputation as the most handsome prince in Europe (not least when wearing white cashmere pantaloons) – struggled to make his voice and intelligence heard.

This curiously female aspect of his plight certainly adds a frisson to a story that would be remarkable by any standards. Thank goodness for historians that it is: for two hundred years after both he and Victoria were born we are being invited to reconsider his influence in exhibitions, a concert (his lieder were performed at a recent Prom), competing TV programmes and a new biography.

The pressure is always on for TV academics to make it sound as if they’re leading us on the most intrepid adventure ever – an Indiana-Jones-style quest to discover the lurking surprises and perilous truths in dusty archives. Respected historian Saul David ably whipped up the drama with the promise of revealing “hidden information” that would allow us to understand the “genius” Albert in more detail than ever before.

Happily the ensuing forty-five minutes sacrificed no intelligence to the adrenalised narrative style, as David traced Albert’s uphill journey from arriving in England from Coburg – ‘the stud-farm of Europe’ according to historian Jane Ridley – to presiding over The Grand Exhibition. Talking heads included the eternally irreverently erudite AN Wilson, whose biography of Albert comes out this autumn, and Daisy Goodwin, whose TV series Victoria – based on Wilson’s Victoria biography – launched several thousand new devotees.

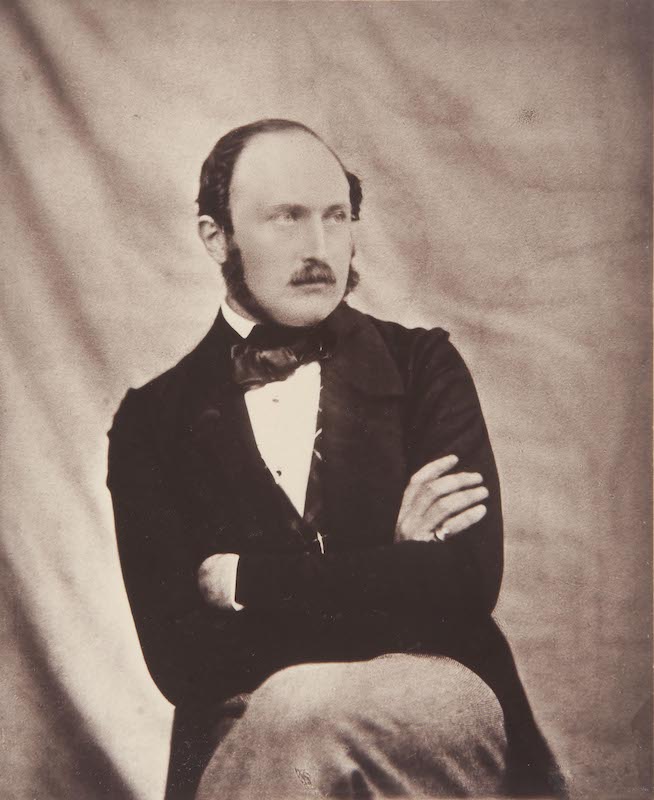

David drew extensively on the impressive royal archive at Windsor Castle, from which 20,000 personal letters, diaries and photos have been digitised for the use of both scholars and the public. From this, “the most complete collection of documents and pictures relating to Albert’s life,” we discovered that his love of art, science and technology made him an early aficionado of photography – as was borne witness by an 1848 tinted print of the 29-year-old prince. It was his intellect and love of new ideas that would liberate him: humiliated, at first, by Parliament when it refused to give him the £50K annual allowance he requested, he started to make his mark by reforming the royal household. As Wilson acerbically commented, one of the most shocking things for foreigners coming to Britain is discovering “how badly everything is run”. In one particularly delicious detail he told of how one person was in charge of cleaning the inside of the windows at the palaces, and the other the outside: since they didn’t co-ordinate, one side was always dirtier than the other, which meant you could never see through them properly.

David drew extensively on the impressive royal archive at Windsor Castle, from which 20,000 personal letters, diaries and photos have been digitised for the use of both scholars and the public. From this, “the most complete collection of documents and pictures relating to Albert’s life,” we discovered that his love of art, science and technology made him an early aficionado of photography – as was borne witness by an 1848 tinted print of the 29-year-old prince. It was his intellect and love of new ideas that would liberate him: humiliated, at first, by Parliament when it refused to give him the £50K annual allowance he requested, he started to make his mark by reforming the royal household. As Wilson acerbically commented, one of the most shocking things for foreigners coming to Britain is discovering “how badly everything is run”. In one particularly delicious detail he told of how one person was in charge of cleaning the inside of the windows at the palaces, and the other the outside: since they didn’t co-ordinate, one side was always dirtier than the other, which meant you could never see through them properly.

The most fascinating thread of this documentary showed that Albert’s genius was to equate good design with a utopian vision of society. One early design was of a stunning model dairy, in which despite the decorated tiles and stained windows, functionality came first, not least in a central fountain that dispensed water for keeping the bowls of cream cool. Osborne House on the Isle of Wight – in which sewage from the palace was used to irrigate the beautiful gardens – was another Albertian triumph. Albert’s love of photography also went beyond creating idealised family albums, not least in the project where he oversaw the photographing of Raphael’s Sistine Chapel tapestry cartoons to create a definitive survey of the artist’s work.

In 1848 – the same year as that tinted photograph was taken – Albert was growing increasingly preoccupied with the spirit of revolution and populist unrest that was sweeping across Europe. The growth of the Chartist movement made him understand that the British monarchy might well be the next target, but even as he fretted about his and Victoria’s future he saw the need to persuade the political class of the legitimacy of the Chartists’ demands. Seeing education as one of the solutions to the hideous deprivations of Victorian inner-city poverty, he built a school for the children of the workers on the Osborne estate, as well as creating a visionary blueprint for social housing. One of his model houses can still be seen today in Kennington.

His greatest venture, of course – the announcement of which was accompanied by suitably agitated violins on the soundtrack – was the Great Exhibition, for which people from all over the world would come to celebrate trade, invention and technology. The opprobrium which he endured for organising this almost broke him: he was accused of being a foreign spy; it was predicted that hailstorms would smash the Crystal Palace; and worries were expressed that visiting dignitaries would be decapitated by falling glass. In the end, of course, it was the historic triumph with which we are all well acquainted. Six million visitors attended. Just a few years later he was made Prince Consort by Victoria – he had arrived.

But the work ethic that made him would also kill him. The signs were to be seen in photographs in which he was clearly ageing prematurely from his mid-30s. In 1861 he was taken ill at Windsor Castle. One of the most moving details in the documentary was the book mark at page 81 of Walter Scott’s Peveril of the Peak, which, as Victoria explained in her inscription, was the place where she had to stop reading the book to him shortly before he died.

It’s typical of the intelligent detail of a documentary which adds much to our understanding of the man whose legacy is all around us, not least in the extraordinary cultural hub of South Kensington whose landmarks were built with the profit from The Great Exhibition. Like all the best documentaries, it left us with the desire to know more, which, given the vast array of archival information that has just been released, is just as well.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Add comment