Best of 2018: Art | reviews, news & interviews

Best of 2018: Art

Best of 2018: Art

Reputations restored and revised: a look back at some of this year's best art shows

Exhibitions routinely claim to be a once in a lifetime experience, but there can be no doubt about the prince among them this year, the Royal Academy’s spectacular Charles I: King and Collector.

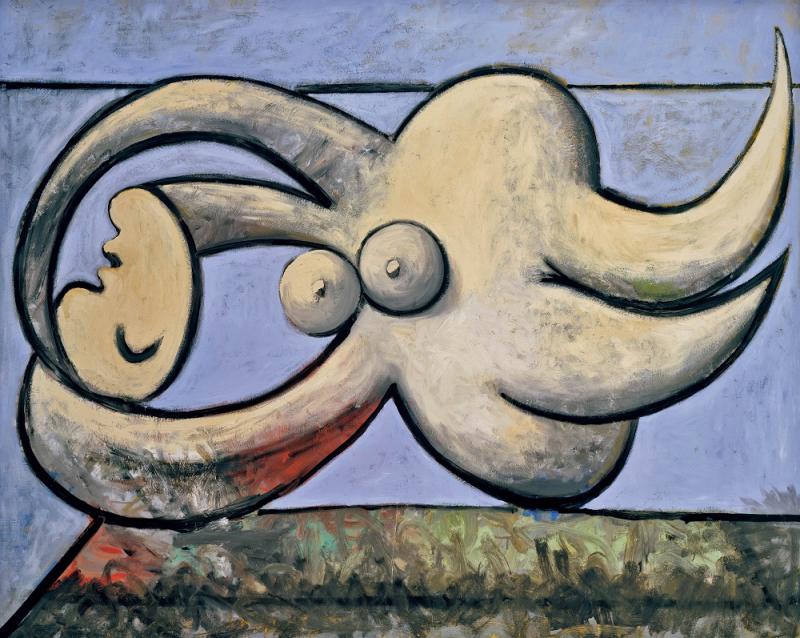

If Leonardo exerts an irresistible pull, so does Picasso, whose legend was supercharged with sex and death for Tate Modern’s show Picasso 1932: Love Fame Tragedy. Despite a peculiarly sparse hang, and rather a lot of less good and sometimes bad works, at the show's heart was the series of monumental nudes, astonishingly coherent as a group, that led the art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler to pronounce Picasso the saviour of painting. The show's fixation on Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s love and great inspiration in that year, seemed to fly in the face of current attempts to release female figures from supporting roles in the margins of great art, and it only cemented the impression of Picasso as a manipulator of women, whose art can be startlingly brutal and at times infantile in its crudeness (Pictured below: Pablo Picasso, Reclining Nude, 1932).

Women were celebrated less ambivalently elsewhere in 2018, the centenary of women’s suffrage marked by the unveiling of Gillian Wearing’s statue of Milicent Fawcett in Parliament Square. Efforts to recognise overlooked women artists gathered pace, with the Barbican Art Gallery’s Modern Couples providing an encyclopaedic and rather too booklike exploration of the exchange of ideas and influence, not to mention emotional fallout, within artistic couples. Performance art pioneer Joan Jonas received a retrospective at Tate Modern, and YBA Tacita Dean had no fewer than three shows in London, at the Royal Academy, the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery. At the V&A, Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up presented the artist through personal possessions - clothes, medical equipment and paintings - sealed away after her death by her husband Diego Rivera, and rediscovered in 2004 (Pictured below: Self-portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States of America', Frida Kahlo, 1932).

Women were celebrated less ambivalently elsewhere in 2018, the centenary of women’s suffrage marked by the unveiling of Gillian Wearing’s statue of Milicent Fawcett in Parliament Square. Efforts to recognise overlooked women artists gathered pace, with the Barbican Art Gallery’s Modern Couples providing an encyclopaedic and rather too booklike exploration of the exchange of ideas and influence, not to mention emotional fallout, within artistic couples. Performance art pioneer Joan Jonas received a retrospective at Tate Modern, and YBA Tacita Dean had no fewer than three shows in London, at the Royal Academy, the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery. At the V&A, Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up presented the artist through personal possessions - clothes, medical equipment and paintings - sealed away after her death by her husband Diego Rivera, and rediscovered in 2004 (Pictured below: Self-portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States of America', Frida Kahlo, 1932).

Receiving posthumous recognition of a singular sort was Jeanne-Claude, who though she died in 2009, continues to be named as co-author to every new work by Christo, whose London Mastaba (Pictured below) was a joyous addition to the Serpentine over the summer, and his first major public art work in the city. A great pile of oil drums afloat on the Serpentine looks like an admin nightmare, and the accompanying exhibition in the Serpentine Gallery attested to the truth of this: this was where Jeanne-Claude came in, smoothing the way with planners, protestors and health and safety officials for every project from the wrapping of the Reichstag to curtain hung between two Colorado mountains in 1972. Can admin be art? Perhaps it is Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s great achievement that this is a question that seems worth asking.

We despatched a special correspondent to the V&A’s autumn offering, Video Games: Design/Play/Disrupt, not being able to muster a sufficiently knowledgeable (youthful) critic among our regular writers. By avoiding arguing for the status of video games as an art form the show side-stepped well-trodden and boggy ground. Instead, it made such distinctions seem rather redundant, its exploration of the design process revealing artists like any other, using concept sketches and other traditional, analogue methods to develop and refine ideas.

We despatched a special correspondent to the V&A’s autumn offering, Video Games: Design/Play/Disrupt, not being able to muster a sufficiently knowledgeable (youthful) critic among our regular writers. By avoiding arguing for the status of video games as an art form the show side-stepped well-trodden and boggy ground. Instead, it made such distinctions seem rather redundant, its exploration of the design process revealing artists like any other, using concept sketches and other traditional, analogue methods to develop and refine ideas.

Dislodging accepted wisdom was at the heart of All Too Human at Tate Britain, which completely revised the genealogy of British figurative painting in the 20th century. It wasn't iconoclastic and Bacon and Freud were still the central figures, but their work was given fresh perspective by casting Soutine and Bomberg as antecedents. Having spent his life marginalised by the art establishment, Bomberg's inclusion as a foundational figure of British modernism set the record straight, and acknowledged his importance not just as a painter, but as a teacher.

A fresh perspective on Monet seems an impossible task, but this is exactly what the National Gallery provided in their marvellous show, Monet and Architecture, earlier in the year, which was, rather surprisingly, the first UK show dedicated to Monet in 20 years. It explored his use of architecture as a frame around which to build his paintings, the vehicle for explorations of light and colour, the uprights and horizontals of manmade structures a foil for his increasingly abstract impressions (Pictured below: Claude Monet, A Hut at Sainte-Adresse (Cabane à Sainte-Adresse), 1867). For an artist who has suffered somewhat from overexposure, this beautifully hung show allowed a new appreciation of Monet's methods, and perhaps even a fresh sense of his motivations.

There was no shortage of ambitious, large-scale shows, with Oceania at the Royal Academy and Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece at the British Museum among the most popular: but it was a single work, not a show, that stood out as truly epic - Christian Marclay's film installation The Clock at Tate Modern. The montage of thousands of film and TV clips functions as a 24 hour clock, the clips forming a strange but oddly articulate narrative of their own, with an overwhelming tension that makes the minutes fly by. The Clock is at Tate Modern until 20 January with a 24-hour screening on 12-13 January, and is one to go back to again and again while you can.

There was no shortage of ambitious, large-scale shows, with Oceania at the Royal Academy and Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece at the British Museum among the most popular: but it was a single work, not a show, that stood out as truly epic - Christian Marclay's film installation The Clock at Tate Modern. The montage of thousands of film and TV clips functions as a 24 hour clock, the clips forming a strange but oddly articulate narrative of their own, with an overwhelming tension that makes the minutes fly by. The Clock is at Tate Modern until 20 January with a 24-hour screening on 12-13 January, and is one to go back to again and again while you can.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Add comment