Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns, National Gallery of Ireland review - experiments in Pont-Aven | reviews, news & interviews

Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns, National Gallery of Ireland review - experiments in Pont-Aven

Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns, National Gallery of Ireland review - experiments in Pont-Aven

Friendship and rivalry among the Post-Impressionists

In the autumn of 1892 Émile Bernard wrote home to his mother that, following the summer decampment to Pont-Aven of artists visiting from Paris and further afield, there remained "some artists here, two of them talented and copying each other.

There are indeed striking similarities and borrowings between O’Conor’s and Amiet’s canvases, but what the National Gallery of Ireland’s new show, Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns, makes clear is that this was not unique to the duo but rather indicative of the proximity and rivalry characterising a febrile period of artistic activity that led to the formalisation of new European movements such as Synthetism, the Nabis, Fauvism and Expressionism.

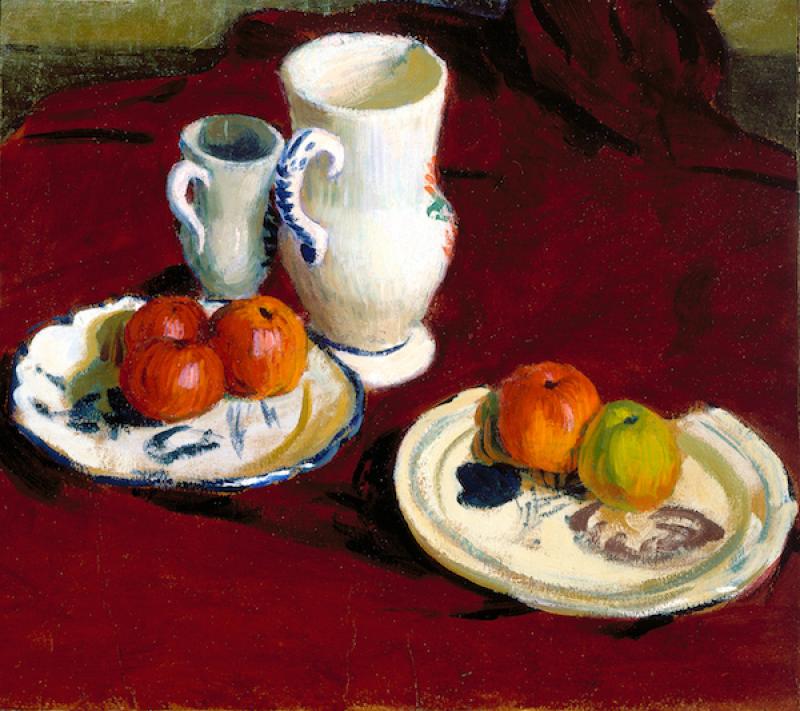

In the wake of the Impressionists having broken definitively from the Academy, new ways of making marks, laying paint, conveying sense and understanding colour led to an array of artistic approaches and O’Conor experimented and borrowed prodigiously. Over the course of the exhibition his work becomes a prism by which to see how the influence of his contemporaries and near-contemporaries travelled. Three still lifes, one by Gauguin and two by O’Conor, relay the compositional and chromatic influences of Renoir and Cézanne; a vitrine holding Amiet’s Post-Aven sketchbook, 1892-3, open at a page depicting Breton women recalls the confident lines and bold movement of Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon, 1898 (not displayed); Vincent van Gogh’s Wheat Field with Cornflowers, July 1890, is paired with O’Conor’s Field of Cornflowers, 1892, to demonstrate how Van Gogh’s pure lines of thick impasto were absorbed into O’Conor’s technical repertoire.

Yet, the difficulty is not that O’Conor’s work is directly derivative, merely that he seldom attains the kind of focus required to deliver something wholly of itself. There’s often something unfulfilled, ever so unurbane about his work. So comparing van Gogh’s field with his, the paint colours are muddier, less assured, and while it feels possible to pitch directly into van Gogh’s maelstrom of cornflowers skittering across wheat heads, O’Conor’s surface feels unavoidably present – a skin packing the image tight against a bleed of feeling. Emotional protectionism is present too in the striking Breton Peasant Woman Knitting, 1893, in which half the subject’s face is striped out by red and green lines attributable to Divisionist optical theory. Incredibly it still registers as her face, but for a humble sitter it’s a reduction that knits her, the background and her labour into a flattened plane of distinctly violent formal technique. Hung next to Amiet’s Breton Woman, 1892, which uses swathes of fresco-thin green for the far side of her tilted, curious face to startlingly graceful effect, O’Conor again cedes to another artist’s greater sensitivity.

Yet, the difficulty is not that O’Conor’s work is directly derivative, merely that he seldom attains the kind of focus required to deliver something wholly of itself. There’s often something unfulfilled, ever so unurbane about his work. So comparing van Gogh’s field with his, the paint colours are muddier, less assured, and while it feels possible to pitch directly into van Gogh’s maelstrom of cornflowers skittering across wheat heads, O’Conor’s surface feels unavoidably present – a skin packing the image tight against a bleed of feeling. Emotional protectionism is present too in the striking Breton Peasant Woman Knitting, 1893, in which half the subject’s face is striped out by red and green lines attributable to Divisionist optical theory. Incredibly it still registers as her face, but for a humble sitter it’s a reduction that knits her, the background and her labour into a flattened plane of distinctly violent formal technique. Hung next to Amiet’s Breton Woman, 1892, which uses swathes of fresco-thin green for the far side of her tilted, curious face to startlingly graceful effect, O’Conor again cedes to another artist’s greater sensitivity.

These comparisons are more informative than they are flattering but canvases which balance subject with technique are notably more poised. The Glade, 1892, striates a deserted forest floor with crimson filaments woven with glutinous hot yolked light. The technical punch is synaesthetic – you can almost smell the hot earth baking. Still Life with Bottles, 1892, dapples light in short glassy dabs across Pont-Aven cider bottles and in the final room, three tumultuous seas lash brazen rocks. Dating from between 1898-1913 they glow, assuredly. Warm Waves Breaking on the Shore at Sunset, 1898-9, seems to lift off the wall with its nacreous play of light on the waves. The sense that O’Conor is settled radiates. He has found his place.

- Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns at the National Gallery of Ireland until 28 October 2018

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment