Ian Rickson: 'I'm an introvert, I want to stop talking about myself' - interview | reviews, news & interviews

Ian Rickson: 'I'm an introvert, I want to stop talking about myself' - interview

Ian Rickson: 'I'm an introvert, I want to stop talking about myself' - interview

The director staging Brian Friel's Translations at the National talks about Ireland, England and the changing face of theatre

Ian Rickson’s route into theatre was not conventional. Growing up in south London, he discovered plays largely through reading them as a student at Essex University. During those years he stood on a picketline in the miners’ strike, and proudly hurled the contents of an eggbox at Cecil Parkinson. He is a lifelong supporter of Charlton Athletic.

In those early years he put himself wholly in the service of new writing. His breakout hit was in Conor McPherson’s The Weir, which went through multiple casts in London and New York. The other playwright whose work he most regularly nurtured onto the stage was Jez Butterworth: Jerusalem is celebrated as a triumph for Butterworth and Mark Rylance, but it was Rickson's too.

He said farewell to his job at the Court with, unusually, a revival of The Seagull starring Carey Mulligan in the title role. As the years have gone on he has dipped into the classic repertoire more frequently. There have been Pinters – The Hothouse, Betrayal, Old Times, most recently The Birthday Party (pictured below by Johan Persson) – as well as Beckett, Ibsen, Sophocles. At the Young Vic he directed Michael Sheen in Hamlet, so far his one and only Shakespeare. Throughout he brings the sensibility of a writer's director bringing new work to fruition. His latest production is a revival at National Theatre of Translations, Brian Friel’s modern masterpiece set in the 1830s when the British Army rewrote the map of Ireland and the Irish language was put under threat of extinction. It stars Colin Morgan and Ciarán Hinds and is Rickson’s first time in the Olivier. A rare interviewee, he talks to theartsdesk about Ireland, England, and the changing face of theatre. JASPER REES: How do you choose a play?

JASPER REES: How do you choose a play?

IAN RICKSON: The older I get the more actually immersed I feel in my work. I won’t say it costs but I put a lot into it. So what I choose or accept has to be freighted with, number one, massive meaning, psychologically, politically, emotionally, for me and I would hope for the world. I’m trying to choose things that I feel are so worth the amount of preparation and investment and endeavour of a company in terms of what they give an audience now.

And so why this play?

If you revive a play like Translations the endeavour had to be to enshrine it as a modern classic. And the boldness of the National is putting that play on the main stage of the Olivier. There is a creative challenge there for me. And to play to 1,200 people each performance and to create a zone where those people come together and think about really really really important things: education, language, empire, nationhood, identity. It’s a very very ambitious deep rich play and feels really like getting out of bed for.

It’s also a play about the often dysfunctional relationship between languages. How do you confront the fact that Gaelic or Irish which most of the characters speak is written in English so their native language seems to be groaning with Latin polysyllables?

The first thing as a sort of explorer-director you go as deep as you can into the personal mythology of the playwright. So I go to Donegal, I go to his house, I read all his plays. I think about him. And one of his big questions was how do I speak in an inherited language? Being a nationalist and being pinioned in Derry, writing the play in 1980 when it was effectively a war zone, and having to use a language that had only been commonly spoken in his country for 200 years or something. So then you’ve got the conceit of the play – and it’s a funny irony that he’s writing it in English yet they’re speaking Irish and the beauty of that conceit in terms of how it empowers an audience. And then you’ve got the trilingual thing of Greek and Latin. My job is to create a culture in rehearsal where language is thrumming with charged energy and meaning and, even if you’re speaking in your own language, it can be prone to all sorts of misunderstandings. And then if you use other languages what that does to you. I’m a Royal Court person. For me the writer, the word and the body of the actor, that is all I need. I’m not brilliant with video. I don’t excel in multimedia. I love a wonderful actor and the word. Translations is great for that. It’s symphonic and it’s complex, it’s got a great story. It’s beautifully choral.

It arrives at an interesting moment in the relationship between Great Britain and the Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. How is that playing out in your head?

The first day of rehearsals was the 20th anniversary of the Good Friday agreement, which is of course under massive pressure now. I’ve got a company of 80 percent Irish actors. The legacy of colonialism, Ireland being the first colony, and what our ancestors did there in relation to now, what’s done in terms of bruising and forming the play and latterly what’s been happening with Brexit and borders is really suggestive. You’ve got these weather fronts: the British army coming in and renaming all these place names; the English-driven national school system which is being set up where everything will be taught in English and school is compulsory. And that will obliterate Irish. All of those things feel so contemporary. In England we’re banishing arts subjects, pushing this very literal mind-numbing national curriculum where creativity is really under threat. So I think it’s a very political play. But it’s not a preachy play. He writes this in the late Seventies. It’s premiered in Derry. The police helicopters are above it on the opening night. People are searched as they go in. You’ve got Martin McGuinness, Gerry Adams, but you’ve also got leading Unionists. A nationalist playwright writes beautifully from the perspective of the English lover, the romantic lead. He’s very complex in terms of avoiding a sentimental homage to old Ireland. It’s beautifully provocative; it’s not sectarian or preachy.

What happens in the first day of rehearsal for you?

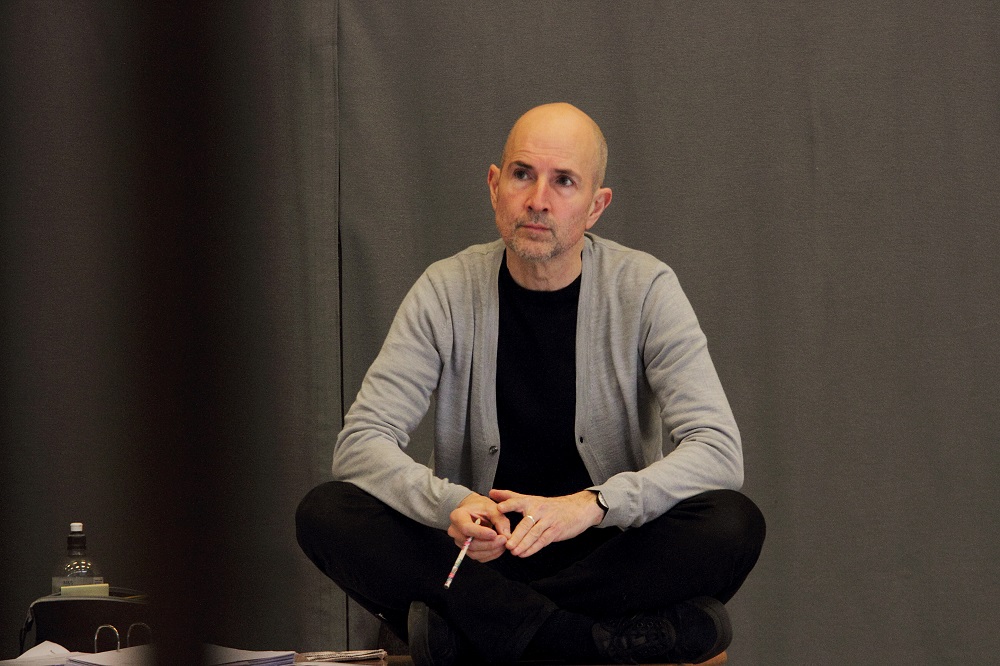

It’s my most nervous moment. I feel like an anxious host at a party and will people be all right? Will they be able to be themselves? So I construct a series of things which might be different from show to show which are devised to banish fear, from myself as well as the actors, which allow us to start constructing the artistic binding a company needs, gets everybody playing but also searching. But I do get a pretty serious work ethic going as well. I don’t do the things you’re supposed to do like start off with a model showing, and then a read-through and a big meet and greet. I try to banish all that so the space is more conducive to everybody in the company feeling themselves. (Pictured below: Ian Rickson in rehearsal for Translations. Photograph by Catherine Ashmore) What did you do for this?

What did you do for this?

I did some nice getting-to-know-you exercises. And then I did a thing about mapping, but mapping the company. Everybody was situated around the room geographically and I asked various questions that related to the play and then moved the map on age to age so we all ended up in London and that allowed us to see ourselves. But it gave a sense of each of our journeys.

And your journey was included?

Sometimes as a director you think, I want to stop talking about myself. I’m an introvert. I’m actually pretty happy in the room where really my subjectivity is quite hidden. So I sort of part took part in that exercise. But I’m really trying to facilitate them all becoming very alive and present.

Why the Olivier?

I approached the National with this play. Then I have a dialogue with them about where a play might sit. I said, “Can I just have a day mucking about with it in the different spaces, the Lyttelton or Olivier? I got all these excellent Irish actors and we went from space to space and they pretty much all said, “Go with the Olivier.” And that was my hunch. Although it’s big the Olivier has a warmth and a scale to it where you can actually feel something intimate can feel epic. The more I read the play I thought rather than a social realist play about Ireland this play is mythic, elemental, it’s got real range. So I went for the Olivier.

Is there a difference between staging plays under different artistic directors?

Yeah. I think so. If you’re a freelance artist coming into a building you’re coming into somebody’s house, and the way they host you and the shadow of their leadership in the building – please don’t ask me to be specific! – is quite impactful. I miss it so much because I love that quality of it. I love the interaction with incoming artists. The way I try and keep that sense of community is just trying to create it with each company.

Would you like to run a building again?

I sometimes fantasise about it, yeah. It’s hard to find a place as a good as the Royal Court. There is something about that building and its mission that was an absolute privilege to be part of. But I like the idea of it.

Did you meet Brian Friel?

I did meet him a couple of times. I didn’t really know him.

You have worked most frequently with Conor McPherson and Jez Butterworth and helped to usher plays of theirs onto the stage for the first time. It’s almost a co-authorial role. Is it important to know a playwright? All I can say is I sort of do the same thing whether it’s Sophocles, McPherson or Friel. Which is try and travel as deep as I can into their shadow, into their unconscious, into their intentions. I remember reading four biographies of Chekhov, reading his letters, going to his houses. In some ways it’s easier to do that when the writer is not around, because you can feel nosey than when pestering a living playwright with loads of questions about their childhood wounds. (Pictured above: Kristin Scott Thomas as Electra, photograph by Johan Persson)

All I can say is I sort of do the same thing whether it’s Sophocles, McPherson or Friel. Which is try and travel as deep as I can into their shadow, into their unconscious, into their intentions. I remember reading four biographies of Chekhov, reading his letters, going to his houses. In some ways it’s easier to do that when the writer is not around, because you can feel nosey than when pestering a living playwright with loads of questions about their childhood wounds. (Pictured above: Kristin Scott Thomas as Electra, photograph by Johan Persson)

There is a great predominance of the male voice in the plays you’ve put onstage. How is you’ve leaned one way more than the other?

I feel embarrassed to say I hadn’t even thought that. Whether that’s a lazy male gaze, I would love to direct more plays by women. When I have I love it. I love difference. But perhaps you would point out something very simple, that by virtue of your gender you might have an understanding of various aspects, characters, whatever, that might be gendered. It also points to an unfortunate thing that the mathematics of classical revivals are way in favour of the male voice.

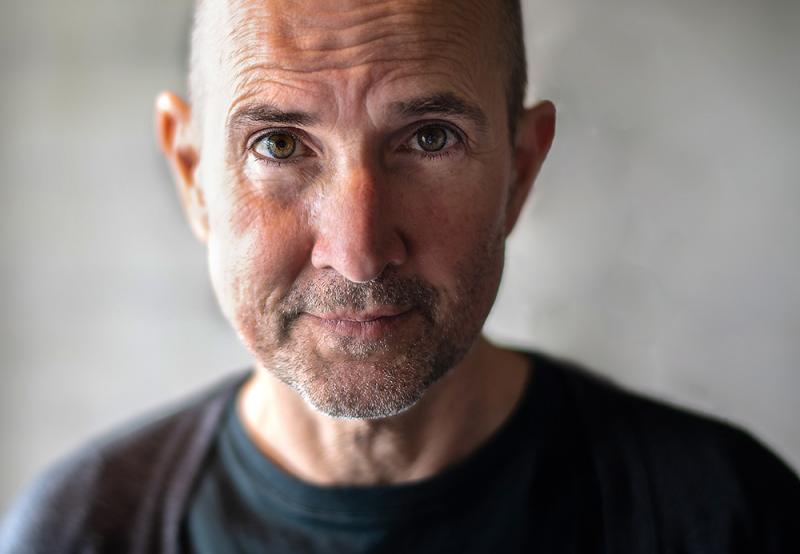

There was your one encounter with Shakespeare at the Young Vic. Did that embolden you to want to do more or was that itch scratched by that one production? Well, I feel a better director having directed Hamlet. I think I learned a lot doing it. It was something I worked on for a couple of years with Michael Sheen (pictured above by Simon Annand). I was really proud of it. But to be honest I think it was really hammered by the critics and to be even more candid that bruised me. The working-class shy boy in me then felt disqualified in my own mind from doing more Shakespeare and I haven’t done one since.

Well, I feel a better director having directed Hamlet. I think I learned a lot doing it. It was something I worked on for a couple of years with Michael Sheen (pictured above by Simon Annand). I was really proud of it. But to be honest I think it was really hammered by the critics and to be even more candid that bruised me. The working-class shy boy in me then felt disqualified in my own mind from doing more Shakespeare and I haven’t done one since.

How has the culture of working in theatre changed in your years as a director? For example, Translations is a mainly Irish cast but you have one actor of African heritage. That is something that simply wouldn’t have happened when you started directing.

On the other hand we might say because of a series of political decisions it’s harder to train and the access to the arts is under threat in a way that when I started directing there was a little bit more of a range of people that were able to be supported going into it. I suppose I feel about theatre the way I feel about the world: things are getting better and worse at the same time. I don’t think I’m going to be lucid about how theatre has changed. This sounds solipsistic but I’m far more able to be searching or articulate about how I’ve changed.

You’ve asked your own question…

I hope I’m better as an artist. But I was thinking recently through a combination of 10 years of therapy and really working on myself, I think I’m a more sensitised person in the room which allows me to be, hopefully, touching wood, more intuitive and better at holding a room. But I also feel that that can shoot me really deep into the unconscious of the play and sometimes that is thrilling, but it’s tiring. I think about the younger me who probably when I was running the Royal Court prepared plays over the weekend and was kind of instinctive. Now I try and do whatever I can to feel into the deep wound that is often the mainspring of a play. I’m just trying to manage at this moment how to do that in a way that isn’t beleaguering for me. But that’s so boring! I’m boring myself!

- Translations, in repertory at the Olivier Theatre from 22 May until 11 August, is a Travelex show where many seats for every performance are £15

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Comments

I was at university with Ian.