Tony Banks: ‘You either do it by diplomacy or you do it by violence’ - interview | reviews, news & interviews

Tony Banks: ‘You either do it by diplomacy or you do it by violence’ - interview

Tony Banks: ‘You either do it by diplomacy or you do it by violence’ - interview

From Genesis to regeneration, the keyboard player's tale

In a career that began in 1967 and may yet have further life in it, Genesis have sold 150 million albums (and possibly more), and in their original incarnation with Peter Gabriel as vocalist were an influential force in the development of progressive rock.

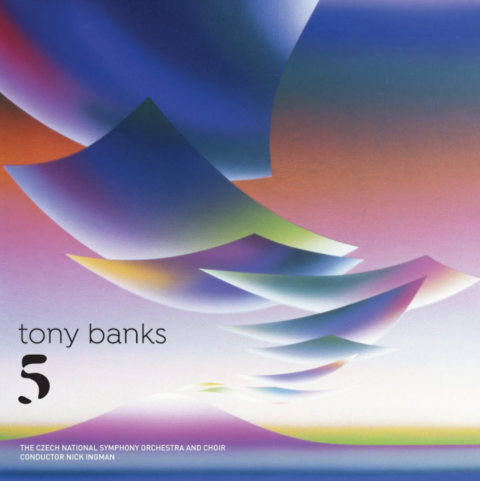

But while Gabriel and Collins became solo stars, the good ship Genesis was powered along by its founder members Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks, who have kept the show afloat with indispensable contributions as both songwriters and performers. When it looked like the band was finally on its uppers in the late Nineties, keyboardist Banks, who already had three solo albums to his credit, decided it was time to pursue his growing interest in composing instrumental music. He’d written several film soundtracks in the Seventies and Eighties, the best known of which was for Michael Winner’s The Wicked Lady (1983), and wanted to try his hand at orchestral pieces. He released Seven: A Suite for Orchestra in 2004, and in 2012 came Six Pieces for Orchestra. Now he’s releasing his latest effort, Five, comprising five new compositions played by the Czech National Symphony Orchestra and Choir, conducted by Nick Ingman. In 2015 Banks, who's renowned for his innovative use of keyboards and synthesizers, was anointed a Prog God at the Progressive Music Awards, but his ambitions as a writer of orchestral music are more modest. “I thought if I ever got to the stage later in my career when I had a bit of time, I might give it a go,” he confesses.

ADAM SWEETING: It was a commission for the 2014 Cheltenham Music Festival which kicked this new album off, wasn’t it?

ADAM SWEETING: It was a commission for the 2014 Cheltenham Music Festival which kicked this new album off, wasn’t it?

TONY BANKS: Yes, I was asked to compose a piece by Meurig Bowen, who was the festival’s artistic director. I think he was a bit of a Genesis fan, and he thought I might like to do it. He said it should be about 15 minutes long. I had two or three pieces on the go at the time, and I decided to really develop this particular one, which eventually became the album’s opening track, “Prelude to a Million Years”. I think having a definite commission did give me an adrenalin shot, because you know that somebody actually wants to hear it. I am always a bit conscious with these things… there’s an episode of Frasier where he had to write the music for a commercial or something, and being Frasier he got the Seattle Symphony Orchestra to play this thing, this silly little theme, and it was pure self-indulgence. I am conscious of that with all this. You do this stuff and who are you doing it for? Does anyone really need to hear this? Would the world be a better or worse place? If you get a bit of response back, that makes a big difference. Anyway the piece was performed live, and the softer passages were fine, but the parts that required real oomph, like the big cello riffs, didn’t work very well at all. At that point I decided I was going to do the album more as if I was doing a rock album, recording the parts separately and then putting it together in layers so I could really get it right. I made very definite and elaborate demo recordings, and we used them as the template for the orchestra to play to. I got Nick Ingman, my orchestrator and conductor, to finish it off, which meant he had to transcribe my orchestral parts, and then add some parts particularly in the percussion, where I’d been a bit lazy. I found it totally transformed the way it sounds, and I now feel the results are much more what was originally in my head when I wrote the music.

But I’ve got so much to learn about this stuff really. It’s been a really steep learning curve from when I did the first album, Seven: A Suite for Orchestra. When I did that one I had to abandon the first recordings I did, I did four or five pieces at Abbey Road studios and I just thought they didn’t sound good at all. I thought, well maybe I just can’t do this, and then I was persuaded a little bit by [producer] Nick Davis. We did another version of the album that was pretty good, and it actually got a few good reviews even from classical people. It sold quite well, which was surprising, and gave me the confidence to do the next one which did even better. I’m a writer, I just want my music out there and to be heard by as many people as possible (pictured below, the blockbuster Genesis trio. From left, Rutherford, Collins and Banks). Are you feeling more at home in the classical arena?

Are you feeling more at home in the classical arena?

Rock with classical music has still got a bit of a thing about it. Rock bands with orchestras has hardly ever worked, whether it was Deep Purple or Procol Harum. Little moments of Days of Future Passed by the Moody Blues worked very well, that was an interesting experiment. But it’s quite snobbish isn’t it, the classical world? If you haven’t been to the right conservatoire and all the rest of it, it can cause a bit of trouble. It gives you a little bit of a leg-up having been part of a famous group, but then after that you’ve just got to take what comes at you, with some people being very dismissive. Also the other thing the classical world likes is for you to perform the stuff live before it’s recorded, so I’m going about it the wrong way really. What I would like is for one of the pieces to be taken out and played as the opening piece at a classical concert, to start the thing off before they go into the major works afterwards. I’ve often come away from concerts thinking those first pieces are the best thing of the evening. But it’s quite a closed shop and quite difficult to get into. I’ve thought about putting something on myself, but there comes a point of how far do you go with this? If people don’t want to hear it they don’t want to hear it, just accept it, boy!

When you were writing music with Genesis, how did that work? Was it quite collegiate? Was there a lot of infighting?

In the very early days, we were very much writing in the original pairs, Peter Gabriel and I, and then Mike Rutherford and [original guitarist] Anthony Phillips. A lot of the arranging was done together. But by the end, with the last few Genesis albums, Mike, Phil Collins and I would go to the studio with nothing written at all. You’d go in one day and think nothing’s happening, then the next day you’d go in and it would be fantastic. Phil was the man with the tape machine and we’d record everything and we’d listen back to stuff and think, "There’s something there, that’s really good”, and sort of work from that. It’s funny, you could write some very concise songs from that as well as more rambling pieces. The best example for me was “Land of Confusion”, which was one of our biggest hits from the Eighties. It started off from a great amorphous mass of stuff and we whittled it down and suddenly ended up with this incredibly concise song, and I was really proud of that. We all knew our roles, I think. I tended to be mainly in charge of the chords and harmony, then Phil would often just warble along on top while he was playing drums. Sometimes his melody line on top of the particular chord I was playing, that combination is what did it rather than either one. And Mike with his guitar riffs, he loved repeating stuff all the time. I don’t think many groups work like that, most groups have one or two key writers, but we didn’t, not at the end. In the early days, certainly on the middle-period albums when Peter first left, I certainly seemed to get the lion’s share of the writing credits. I think I just tended to shout louder than everybody else. There’s a way of working – you either do it by diplomacy or you do it by violence. I tended to do it by violence. But having said that, we all got on well and I think we all liked everything that ended up on the record, even if it came more from one person than the others.

Was Peter Gabriel much of a composer, in terms of music rather than lyrics?

Was Peter Gabriel much of a composer, in terms of music rather than lyrics?

Yes, Peter was definitely a writer, he played piano (pictured right, Gabriel and Banks at the Progressive Music Awards). Back in the early days we used to write more individually, he’d write bits and pieces here and there. It tends to end up that the instrumentalists are going to end up writing more of the music, so Mike and I tended to do slightly more, but Peter was very heavily involved and obviously he being the vocalist ended up writing more of the lyrics. By the time we did The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974) he wrote all the lyrics, which for the rest of us wasn’t quite so easy. I think we wanted everything to be a bit more distributed, but looking back on it now it doesn’t worry me too much, though at the time it was a little bit contentious. Peter and I used to fight a lot, though we were very close friends. There was a period when Phil first joined the band when we used to argue quite a lot. It was a difficult time for us because we didn’t know where we were going and didn’t have much success. Poor old Phil came in, a sort of jolly chap trying to keep the peace, and Peter and I were shouting at each other and walking out of the room. That only lasted for a short period of time. I love Peter and we’re very good friends still, but being friends within that situation can be quite difficult.

It must have been fascinating to be in the middle of the creation of prog rock?

It started I think with the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds – people realised you could do more in pop music than just bang out the four or five chords. That can be great, but Pet Sounds did extraordinary things in terms of harmony and arrangements and stuff, and that led to Sgt Pepper and the early prog bands. The first time I ever heard stereo I think was Procol Harum’s Shine On Brightly. Then also Fairport Convention’s albums Liege & Lief and Unhalfbricking, which had quite a profound influence on us as writers. You had this slightly folky element but also the more traditional prog feel. It meant you stopped trying to write pop songs and wrote what you felt like writing, and there was an outlet for it out there, there was an audience that seemed to really like this kind of stuff. There was a whole load of bands out there of various degrees of goodness. The Nice was the first concert I ever went to see and it was just so exciting to hear this kind of stuff, quite complex playing and just the sheer volume and the fact that everything kind of went everywhere: I thought that was fantastic (pictured below, Thotch? No, the Gabriel-era Genesis).

Were there many venues where you could play in the early days?

Were there many venues where you could play in the early days?

For four or five years it was fantastic from that point of view. You’d play a club, you’d support a band, and then months later you’d go back as the headliners, that was how it worked for us sometimes. But you had to accept the fact that sometimes you’d play to very few people, I think our record was two people at a place in Beckenham, the Mistral Club. We used to go to these blues nights on a Monday, and we got there and there were just two girls who’d come, obviously hoping to meet some boys. They were sat right at the back, very self-consciously, not wanting to be there at all, so we invited them up to the front and introduced ourselves and said "hi". Did our show for our fiver or whatever it was and that was it. Did you see Oh Lucky Man? It’s the only film I can think of that actually got that feeling of what it’s like being in a van, and driving back as the sun’s coming up and you’re going past Scratchwood services, and that’s what our lives were for three or four years, combined with flying on dodgy American airlines to get from A to B. We were big in Italy before anywhere else, we were playing to 10,000 people in Italy then coming back here and playing to half a dozen people in Scunthorpe. It was like that in America even more so, because you could be really big in Philadelphia but no-one had heard of you in Tucson. California took a little bit longer, but it was pretty much just LA and San Francisco.

Bill Bruford (drummer with Yes, King Crimson and briefly Genesis) has this theory that prog was a very English phenomenon, created by public school choirboys.

Well it probably was. We always cited hymns as a big influence on us. Our roots were hymns, and in my case musicals of course were quite a thing, because the first records we had at home were musicals, especially Rodgers & Hammerstein, Oklahoma, the King and I. Also My Fair Lady and West Side Story. I loved this music, and I think it’s definitely been an influence on my writing since. People like Burt Bacharach in a sense followed that up. Pet Sounds was a big hit album over here, probably because it had “God Only Knows” on it which was a very sophisticated song in itself, but what Brian Wilson was so brilliant at was making what was quite complicated sound really simple. So that broke barriers – you didn’t have to do C, A minor, F, G for the rest of time, you could do this other stuff, so it became a possibility for us (pictured below, Genesis reunion 2014). I believe there’s a biography of you that was only published in Italy?

I believe there’s a biography of you that was only published in Italy?

Yes, by Mario Giammetti. It’s never been translated as far as I know. There was this plethora of books out there, and we did a book about 10 years ago, the group, all of us together, with the idea that this should put the book thing to rest (Genesis: Chapter and Verse, 2007). We all okayed it, thought that’s fantastic, then of course Mike did a book three or four years ago which I found a bit difficult myself (The Living Years, 2015). Then of course Phil has done his book (Not Dead Yet, 2016) which I don’t dare read, though he tends to be nice about people actually, and then there’s Richard Macphail, our old roadie guy, he’s done a book (My Book of Genesis, 2017), so they’re all coming out. Steve Hackett says he’s got a book coming out as well. I keep getting people asking me to do a book. It’s a pretty boring life really. If you’re a fan you might be interested in the chord structure of “Firth of Fifth” or something, but I dunno. I think I’m going to leave that for a long time. I thought if I’m the last survivor and all the rest are gone, I could then write a book saying how I did it all and they just watched me. I’ll have to wait until then though. Even though it’s true!

Phil’s book sold well, didn’t it?

It did pretty well. Phil is controversial but a big star, y’know. He always seems to be the butt end of so many jokes, which is a shame. It’s curious, because people can be very rude about him, but I hardly know anybody who doesn’t like “In the Air Tonight”, particularly the drum riff. That’s got to be the greatest drum riff of all time, hasn’t it? It’s just such a fantastic moment in pop music.

When I worked at the Melody Maker, Phil used to ring up and complain about things we’d written about him.

He did, and of course that played up to it. I said, “For God’s sake don’t do that, be like me, don’t read anything.” I just don’t read anything any more, I find it all upsetting. Even when they’re nice about me I find I’m upset because it’s never quite right. But when they’re nasty about you, you just don’t want to know about it. I’d managed to avoid reading any reviews of The Lamb Lies Down, and some guy sent me one and said read this! I thought it must be great, but it was terrible. I don’t need to read this stuff! We’ve never really had a period of what you might call ecstatic reviews, but it doesn't seem to have mattered too much.

Will classical critics like 5?

I think they’ll probably ignore it in the main. I sort of approve of the attitude of, “If you’ve nothing nice to say don’t say anything at all.” What’s the point, y’know? It was very much a thing with some of the rock papers at a certain stage to really lay into stuff they didn’t like, and I’d say if you don’t like it just don’t talk about it. I think the trouble is everyone kind of waits for everyone else. If somebody suddenly said, "Oh this is fantastic", then maybe others would give it a listen (pictured by Emily Banks, below). How much credit do you give to Genesis’s manager, Tony Smith?

How much credit do you give to Genesis’s manager, Tony Smith?

Well, he sorted us out really. We were a complete financial mess when he came on the scene. Which was one of the reasons we wanted him, because we’d seen how good he was at organising the tours and stuff we’d been on. He’d been a promoter and had done a couple of tours with us. I think we needed someone like that to sort us out financially, but also staying away pretty much from the artistic side of it. But also very good at making us do stuff. He’d always add a few dates and say do this, do that, and "I think you’ve got to have that" – you need someone who pushes you all the time. But in terms of the music, no-one has ever pushed us. Very lucky, because I read about a lot of groups where their output has had quite a lot of control from others. We never had that, we were able to do exactly what we wanted. In the late Fifties and early Sixties the whole thing was controlled by these Svengali figures in the background, and in the late Sixties it started to change. Peter Grant was probably the first manager to really put his foot down and get money for the artist rather than it all going elsewhere, and I think Tony followed very much in his wake and proved to be very effective for us. So yes, important.

- 5 is released on BMG Classics on 23 February

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Comments

Obviously hasn't listened to

I agree with Alan. Procol

Tony is the greatest. So by

Great interview, funny guy,

Great interview! Am really