Bolshoi's controversial Nureyev ballet opens – to ovations and bans | reviews, news & interviews

Bolshoi's controversial Nureyev ballet opens – to ovations and bans

Bolshoi's controversial Nureyev ballet opens – to ovations and bans

Creator Kirill Serebrennikov, under house arrest, denied permission to see his own ballet

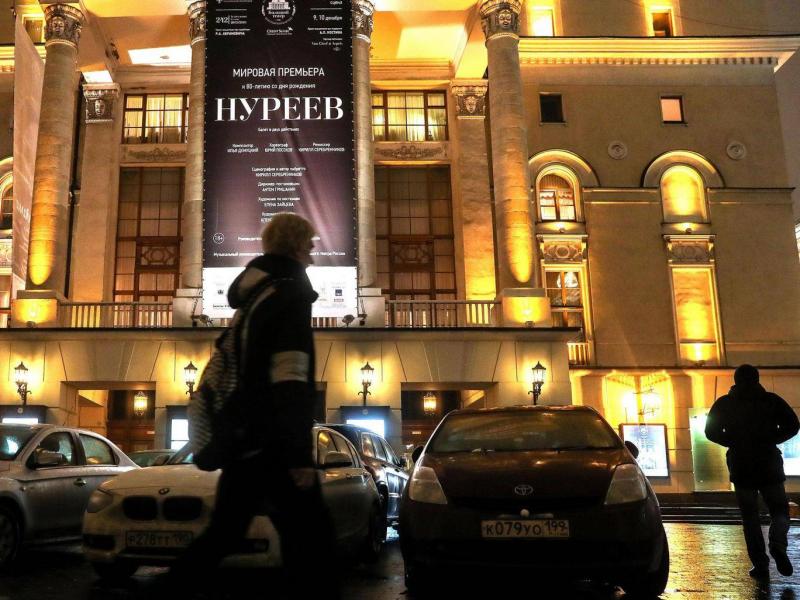

Nureyev, the most notorious new production at the Bolshoi Ballet’s modern history, premiered last night in Moscow to a 15-minute standing ovation and exclamations of official approval even by Putin’s press secretary – but the ballet’s creator and director languished under house arrest, refused permission to see his

Serebrennikov, a leading figure in Russia’s contemporary theatre and a vocal critic of censorship, had been implicitly slapped down by the Bolshoi Theatre when his ballet's premiere was cancelled in July two days before its planned premiere in a swirl of conservative protests about the candour of the portrayal of Nureyev's homosexuality, and particularly some nude images of him. Since then he has been fighting government charges of embezzling public funds at the theatre he heads, and is under house arrest at least until January 19 – accusations widely decried by leading arts figures as politically motivated to intimidate him. One of his most eminent defenders was the Bolshoi’s chief, Vladimir Urin, for whom he had already delivered a successful new ballet the previous year.

Nureyev's sudden last-minute cancellation last July was read by many as a signal of goverment pressure on Bolshoi boss Urin, who admitted that he had been phoned by the arch-conservative Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky. Rumours raged that Medinsky had forbidden the ballet to go ahead without censoring some of its sexual content. For social and religious conservatives Nureyev (pictured above) was problematic twice over: because he had both spurned his country for the West, seeking freedom only available outside Russia, and was openly homosexual. For nitpickers, the complaint was that Nureyev wasn’t even a Bolshoi dancer – he was from the Leningrad opposition.

Nureyev's sudden last-minute cancellation last July was read by many as a signal of goverment pressure on Bolshoi boss Urin, who admitted that he had been phoned by the arch-conservative Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky. Rumours raged that Medinsky had forbidden the ballet to go ahead without censoring some of its sexual content. For social and religious conservatives Nureyev (pictured above) was problematic twice over: because he had both spurned his country for the West, seeking freedom only available outside Russia, and was openly homosexual. For nitpickers, the complaint was that Nureyev wasn’t even a Bolshoi dancer – he was from the Leningrad opposition.

Urin denied any intimidation. He said the ballet was highly complex, its many different aspects involving a large new score, an innovative new use of text and stage effects, and new choreography by a Russian choreographer based in San Francisco, Yuri Possokhov. It had proved too difficult to bring together in what proved too short an allocated rehearsal period, and he postponed it for a season.

Bolshoi dancers erupted on social media, mourning that they feared a significant new work would never see the light. The leading ballerina Maria Alexandrova, who dances Margot Fonteyn in the ballet, posted Malevich’s Black Square painting on her Facebook. However, dress rehearsal footage also posted on social media showed a raw full-length ballet of many elements only barely come together, a worrying state of affairs for a risky work with so much riding on it.

The visuals included images of a naked Nureyev, right down to his strawberries (a Russian colloquialism for genitals)

What the public eye fastened on was that the visuals included images of a naked Nureyev, right down to his "strawberries" (a Russian colloquialism for genitals). The rights to the famous photograph taken by Richard Avedon, seen for only a couple of seconds, were reported to have cost $400,000.

Previously an opera production of Wagner’s Tannhaüser in Novosibirsk was cancelled because of conservative outrage at a visual poster considered sexually provocative (its director and the theatre director both lost their jobs). The Nureyev staging was seen as a further test case for artistic freedom, challenging Putin’s recent ruling on Russia’s core social values which his Culture Minister Medinsky has laid down in the arts world with a particular rigidity. It was as a result of Medinsky’s decree that any arts project receiving public funds should not offend these “fundamental values”, that recently the sexuality of legendary Russian creators, including the composer Tchaikovsky and the film director Eisenstein, has been facing somewhat improbable remastering.

But Urin told a press conference last week that the production was largely funded from sponsorship and the theatre's own resources, not answering how much might be down to taxpayers. He conceded the production was very expensive, and if it had only a few performances would not recoup the cost. These December performances were heavily papered with sponsors and supporters, and the few hundred public tickets available were restricted severely by passport ID, restraining Russia's traditionally voracious touts.

On the artistic front, Urin was caught between two waves of criticism. On the one hand, an outcry from leading voices in the arts world that he caved in to government censorship – echoing the very conditions that Nureyev himself escaped from – and on the other the unexpected roar from the Bolshoi Theatre’s embarrassed trustees, a group of wealthy international businessmen and oligarchs, who insisted that the theatre must save face by premiering the ballet much sooner than next May, as Urin had announced. Hastily two dates were found in December for a pair of premiere performances of Nureyev. The May 2018 performances remain on schedule.

Nureyev is a role model of ambiguous interest in Russia today

How the ballet chooses to portray Nureyev, a role model of ambiguous interest in Russia these days, may be less significant in the end than the kitchen story. Which in a way is logical, given the subject himself. Nureyev, the Kirov Ballet’s raw brilliant talent, developed and polished his dancing and artistic scope in the West, which touches a nerve for the older former Soviets who litter the Russian ballet world. He also inspired bitter envy with his acquisition of world fame and riches in the free world. Celebrity culture is seen by many Russians as a symptom of Western decadence. And Nureyev’s unfettered freedom to love in the West would not be possible in today’s Russia, where LGBT rights face rising obstacles.

Clearly there is hugely interesting content possible in the ballet – much of it explicitly challenging modern Russian attitudes. But the fact that the show’s creator and director was prevented from overseeing rehearsals and even from seeing his premiere raises major questions, given the apparent triumph of last night’s opening.

Urin insisted at a press conference on Friday that he "has not noticed" any changes, and if anything has been changed it has been by choreographer Possokhov with Serebrennikov’s agreement. The dancer playing Nureyev, Vladislav Lantratov, has told a newspaper that "as far as he knows, as far as he hears", Serebrennikov has been consulted about all developments. It rather begs the question of whether the detained director’s current trials can be considered to have no bearing on his artistic decision-making. It also arguably suggests that the six-month delay has averted a dangerous flop and converted it to a triumphant flag against censorship.

So will Nureyev be accepted as the creation Serebrennikov had intended? Will his dubious criminal charges melt away in the heat of the official applause for his fully realised, uncensored ideas? Has Possokhov's improved choreography saved the day? Or will the credit be put down by cynics to a committee who saved the Bolshoi Theatre’s wobbling reputation by blue-pencilling what was inexpedient? We shall find out, no doubt, for no production in ballet history has been more talked about in the world than this one – perhaps there will be a ballet about this ballet in time.

Putin's press secretary said despite its debatable moments, the ballet is a world event

One early critic today (Maya Krylova in Gazeta.ru) makes the point that inevitably most of the discussion to date had to be about the making of the ballet until people actually could see it. And she praises the production wholeheartedly for dealing full-bloodedly and insightfully with Nureyev as a character, as a seeker of freedom, and as a lover in male-on-male choreography (for him and his rival and lover, the dance star Erik Brühn) of "frank eroticism and yet also of spiritual, artistic integrity”.

The official Russian news agency TASS reports approving comments of prominent spectators after it, including Putin’s press secretary, Dmitri Peskov, who said that despite its “debatable moments” it was a world event, with "nothing provocative" about it.

Overall, this operatically unfolding scenario could only occur in Russia. Such a bold and experimental enterprise, coupled with such extraordinarily poorly managed implementation, would be inconceivable at the Royal Ballet. (I don’t think we can compare Serebrennikov with, say, Wayne McGregor – Javier de Frutos, perhaps.) The defiant subject, the historical nest of worms, the daredevilry of the commissioning by the country’s flagship ballet company, the inept cancellations and interferings by state, church and theatre board, the arrest of the creator, the atmosphere of fevered social conflicts – there is a truly heroic incoherence to all the elements.

Yet indications are that the delayed show, and the authorities' handling of Serebrennikov, has delivered an enhanced advantage to the liberals, rather than the conservatives. Its creator now represents a modern avatar of his subject – a man who triumphed in adversity, in absentia. Vive l’artiste seems to be the overwhelming message of this weekend's Russian audience. However, in Russia, it always profits to take the longer view, and many consequences still have to flow.

Above: A scene from Serebrennnikov/Possokhov/Demutsky's Nureyev for the Bolshoi Ballet

Above: A scene from Serebrennnikov/Possokhov/Demutsky's Nureyev for the Bolshoi Ballet

THE SYNOPSIS (from the Bolshoi Theatre)

ACT I

The Auction

After Rudolf Nureyev’s death his property is being auctioned in New York and Paris. Each of the items on display contains a part of the great dancer’s life.

Rossi Street

Nureyev’s studying at the Vaganova Ballet School in Leningrad, his graduation concert, his early career at the Kirov Theatre. Nureyev’s success goes hand in hand with constant denunciations, both at home and during tours abroad.

A Leap to Freedom

Paris. After his legendary ‘leap to freedom’ Nureyev is left alone. His childhood memories entwine with the uncertainty that awaits him.

Nureyev meets the Parisians and tries to imitate their behaviour – to move like free people do.

He is fascinated by the dances of men in drag in the Bois de Boulogne.

A Letter to Rudi. The pupil

Nureyev’s pupils and colleagues – Charles Jude, Manuel Legris, Laurent Hilaire – remember him as an artist, as their friend, as an important part of their lives and the entire human history.

The Portrait. Rudimania

Nureyev’s photo session with the famous Richard Avedon in the latter’s studio. Avedon gets the dancer to behave as natural as possible.

Nureyev is admired by all and stalked by paparazzi. The high society is enraptured by his provocative behavior.

Erik

Dance and mutual passion unite Nureyev and Erik.

ACT II

Grand Gala

Worldwide triumph. Partners change, roles change, music changes – only the great and inimitable Nureyev stays the same.

He isn’t going to let anyone take his place.

A Letter to Rudi. The diva

The great ballerinas, Nureyev’s partners – Alla Osipenko and Natalia Makarova – address him through time and eternity that lie between them.

Le Roi Soleil

Nureyev reigns like the Sun King, enjoying the exquisite singing and sensual paintings.

The Island

Beneath the gorgeous outfit of the Sun King there is a lonely Pierrot devoured by disease.

The Shadows

Nureyev is not only a dancer and a choreographer: he becomes a conductor too.

He stages La Bayadère, his last production. But he is surrounded not only by the legendary Shadows.

The music stops. Nureyev keeps conducting the silence.

- Further related stories about the Bolshoi can be found on my blog ismeneb.com

- The Bolshoi Ballet webpage for Nureyev

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment