Remembering Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017) | reviews, news & interviews

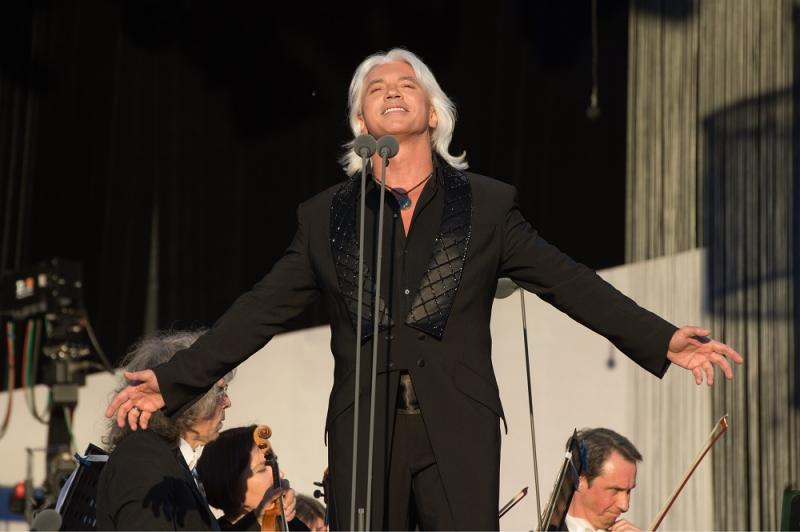

Remembering Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017)

Remembering Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017)

The great Siberian baritone, who has died at the age of 55, leaves behind a golden legacy

A certain online scandalmonger and coffin-chaser likes to preface news of deaths in the musical world with "sadness" or "tragedy", usually when neither he nor we have heard of the person in question.

Soul and sound were there right from the start, when only a singer of this calibre could possibly have deprived Bryn Terfel of the title of 1989 Cardiff Singer of the World (Terfel was awarded the Song Prize, and both sustained equally world-class careers thereafter). This film from the competition shows us what made folk melt about Hvorostovsky's delivery and tone in an aria which no-one has ever sung better – Prince Yeletsky's aria from Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades.

The breath control and the phrasing, like the best of cellists bowing in long lines, remained hallmarks. But when I interviewed Hvorostovsky for Gramophone in 1992, he was well aware that beauty of tone wasn't the only thing to sustain a career: "There's a wonderful story by Turgenev called Singers, about a competition between two voices. The first performer comes and sings, and everyone's terribly excited, because it's a wonderful, rich voice, and he has a huge success. Then the second comes, and he sings so quietly that at times the orchestra can hardly hear him. But he creates a huge, nostalgic, melancholic, very sad effect: everyone in the audience is in tears because they remember some sad event in their lives. That's a lesson to be learned, because some of the songs don't need a huge voice – you have only to talk from your soul, from your heart."

He was also keen to give western audiences a "better impression" of a song like "Dark Eyes" ("Ochi chorniye") than Pavarotti had done in the Three Tenors concert: "Actually I was so surprised at the totally clear way in which Pavarotti enunciated the first two words, but still it was done in such a fashion as to ignore the very deep feelings which lie underneath. I find this song exacting because of the close relation of the words and the music. It's a simple idea, a song about lost first love, but in performance it can be incredibly rich." Hvorostovsky performs "Dark Eyes" below in 2002.

The CD he was talking about, Dark Eyes - Russian Folksongs with the phenomenal Ossipov Russian Folk [Balalaika] Orchestra, remains a classic of its kind, and the intimate numbers – especially two that are unaccompanied – bear out what he told me. Growing up in the Siberian town of Krasnoyarsk, he spent the most time with his grandmother, who "knew thousands of folksongs... she sang while she was working in the kitchen, and I jumped around to those songs. So although I heard the 'official' folksong style screamed at me all the time from radio and television, I really learned from my grandmother, because she sang the music in the right way."

Hvorostovsky's unaccompanied delivery of the folksong 'Nochenka'

There were criticisms that the voice was not a huge one, that it didn't always carry in large opera houses, least of all in the bigger Verdi roles, and that the tone colour could be unvaried. But the cantabile was always peerless, and under the right director – as, for instance, with Robert Carsen in the Metropolitan Opera's Eugene Onegin – Hvorostovsky could be a fine and nuanced singing actor (when I reviewed his last Royal Opera Onegin, I didn't realise he was already ill, and courageously going on with the show). His performances, both live and on CD, of Russian romantsy or romantic songs, from Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov to Shostakovich and Sviridov, are also peerless. Later ventures into bizarre Russian pop, the posh'lust or vulgarity of Putin-era bling, will fade into insignificance; the artistry of one of opera's great singers from any era remains.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Add comment