theartsdesk Q&A: Composer Nitin Sawhney | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer Nitin Sawhney

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer Nitin Sawhney

Musical pioneer discusses Dystopian Dream for dancers, the nature of genius, and Ed Sheeran

Composer, producer and multi-instrumentalist Nitin Sawhney is one of Britain’s most diverse and original creative talents.

Although he started learning the piano at the age of five and had completed grade eight by the age of 11, he made his public reputation alongside Sanjeev Bhaskar as an actor and comedian in the BBC sketch show Goodness Gracious Me, before returning to music professionally with his 1994 debut album, Spirit Dance. The son of Indian immigrants from Rochester, Kent, and for many years the only non-white boy at school, he cut his teeth on the music scene in the Medway towns, where he knew musicians including school friend and acid-jazz pianist James Taylor, and the polymath Billy Childish.

In May this year he received the Ivor Novello Lifetime Achievement Award. He spoke to me about projects new and old, the profit motive, Ed Sheeran, the importance of giving young musicians a chance, and the philosophical implications of virtual and augmented reality.

MATTHEW WRIGHT: Sadler’s Wells’ new dance version of your 2015 album Dystopian Dream premieres in Luxembourg next month. How much involvement have you had in the production?

MATTHEW WRIGHT: Sadler’s Wells’ new dance version of your 2015 album Dystopian Dream premieres in Luxembourg next month. How much involvement have you had in the production?

NITIN SAWHNEY: Originally I was in it, as a director, but I took a view that if I gave something to somebody to remix I wouldn’t look over their shoulder the whole time, and decided to step back. I do advise them, I do talk to them about it, but they have found they own way into it, which they needed to. I also brought in Eva [Stone], one of the singers on the album, and she’s in the show, so in a way I’ve kept a strong connection. I trust her. She’s got a great sense of musicality. She sings a lot of the songs live, so brings the album to life.

I’ve been watching a couple of rehearsals. The aerial work, the projections, and Hussein Chalayan’s costumes all look amazing. It’s a very cool thing, which works because it gets into the emotional places that the album goes and where I went. It’s strong, visually, a powerful experience.

When you see the see the dance performed, does it give you a new perspective on your music?

I don’t know if it’s changed my feelings – it’s like looking at the same thing through multi-dimensional lenses. It’s the same picture but you've been given new lenses. It feels different but it’s the same picture.

Did you have dance in mind when you wrote it?

I write very visually. I always have images and dreams in my head. There were lots of images that inspire the lyrics and music. A lot of it was direct feelings I had when I was by my dad’s bedside when he passed away. It was like looking at those feelings through a magnifying glass and turning that into one big journey.

You’ve described Dystopian Dream as much darker than your previous work. What has brought about the change in mood?

It was to do with my dad dying. A lot of it lyrically and metaphorically is to do with feelings. It was a cathartic album to do with loss.

Your music combines Indian and European classical music, blues, jazz, hip hop, soul, flamenco, and dance beats. What connects these influences? How do you keep all of this in your head at once?

There’s nothing as honest as being spontaneous

It’s like words, or languages. If you speak different languages you don’t think about keeping them in your head, they’re just there. I was very lucky to have lots of training in different kinds of music when I was young. I guess all of that is part of my vocabulary. I don’t ever think about it too consciously, which I’m happy about. I don’t ever think, I’ve got to put in something Indian here, or some flamenco. That’s my palette of sound, and I find it all interesting. I always have a mood that’s underlying what I do, because I’m not a happy-go-lucky individual. I have a melancholic way of looking at the world, and I suppose sometimes that comes out.

Does it make it harder to write a new piece if you don’t have the template of a particular genre – whether that’s a symphony or a pop ballad – to work with?

I do have that sometimes, if I’m writing for a film, or a piece that’s specifically for dance. I have to think of the narrative and psychology of what I’m writing for, and the psychology of the directors, or the protagonists, or whatever, it’s just trying to find your way into building a vocabulary that represents the project and not purely what you feel. It’s not as cathartic as writing an album, which is pure expression of the deepest part of your soul. If I’m writing for a film, I have to find my way into the soul of the film, or whatever. If you’re writing for a pop song, you might look at it quite analytically. I find all of it interesting and challenging.

You’re performing twice during the Globe’s Festival of Independence, one of the appearances specifically about your relationship with India. What does that anniversary mean to you?

The India and Me gig was basically an improvisation, with me chattering for two hours. That was intentional: I don’t want to sit here and intend to make people react in any given way. I just want to be honest with whatever comes out, and there’s nothing as honest as being spontaneous. I enjoyed that. At the same time, I knew I would be talking about my dad, about partition, certain things that happened to me in connection to my heritage and my relationship with India and my perspective on India, so I guess I flowed with that and played music that related to that as well. Tonight it’s very much a band gig, playing several of the tracks from Dystopian Dream. I’m excited that it’s at Shakespeare’s Globe. There’s one track I wrote ages ago, which I credited to me and Shakespeare, “O Mistress Mine”, Feste’s song from Twelfth Night, so I’ll probably perform that. Last year I played for Shakespeare Live, for the 400th anniversary, at the RSC in Stratford-upon-Avon, so it’s interesting performing now at the Globe. I find Shakespeare very exciting, and I always did as a kid. He’s a master of narrative, and that’s what I’ve always respected in how to create musical journeys: it’s how to create a strong narrative that’ll draw people in a dramatic arc in that Gustav Freytag way of drawing people into a world, and getting them to inhabit that same world.

From early in your career, with the Radio 2 show Nitin Spins the Globe, you’ve been educating British audiences, then worldwide audiences, about music from India and other cultures the audience perhaps wasn’t familiar with. Is education an important part of you motivation, or is it just about putting on a good show?

I would find the idea that I would be an educator, through a radio show, patronising. I would look at it as me sharing what I think and feel about music. I tend to approach most things like that. If I’m doing workshops, I think, I’ve got this stuff to say, but I might learn from some of the people in this workshop, which I have done, many times. I find it fulfilling, working with young people, I learn loads from them all the time, it’s fantastic, but hopefully it’s mutual. That’s how education should be: sharing experience and knowledge but also updating your own from younger artists. For example, Kara Marni, a brilliant young singer, is going to sing with us at the Globe. Most of the singers we work with are young and up-and-coming, but very special. I’m blessed in that way. I’ve worked with some amazing artists on their journeys.

Since the Sixties there have been well-known western musicians who have tried to incorporate Indian music into their work. Some, for example John McLaughlin, are serious about it, others less so. Was he an influence? Others?

He’s an amazing bloke, and was a huge influence. Shakti was one of my favourite bands growing up, because I never knew that was possible, until I heard them. Shakti opened my eyes to the possibility of that combination. I grew up as a classical and jazz musician, and I played tabla and sitar as well, but I’d never heard anybody reconcile the two. To hear what Shakti were doing, it was, "Oh wow, there’s this!" People of the calibre of John McLaughlin and [tabla player] Zakir Hussain, these were the cream of jazz and Indian classical music, and I was blown away. Also the albums Meeting of the Spirits (1979) with Paco De Lucia and Larry Coryell, and Passion, Grace and Fire (1983), all of these influenced me, but at the same time I was aware that I didn’t want to be a muso. I grew up playing a lot of complex music, but when I was growing up I also played in a punk band, I was doing lots of different things, and there’s a sharing and communicative aspect of music that’s important, too.

Sometimes when I was living through the punk scene, I realised there were lots of bands who were up their own arses, who didn’t give a shit about what the audience thought, and I decided that it’s great to be cathartic and expressive, but it’s also about sharing, and having an awareness of the audience, which is why I enjoyed DJing. I used to love playing Fabric, because you see an audience react to what you do. It’s an immediate response. Same with comedy, that’s why I did that. You get an immediate visceral reaction. Sometimes musicians get so lost in being musicians they forget how powerful a means of communication and sharing music is.

You mention Fabric, and here we are, in an area [in Sawhney’s Brixton studio] which has changed a lot in 20 years – are you concerned about the pressure on performance spaces that gentrification has applied. Can we do anything to protect them?

That’s a massive conversation about politics and the way the world runs, and not just England. A lot of clubs closed down very quickly to make way for real estate. That’s about maximising profit. We live in a world that’s motivated by greed. It’s hard to keep anything that has artistic integrity or is about an altruistic sense of helping kids find themselves and have a good time moving to music. That will never measure up in a corporate mentality when they can make a hell of a lot of money from real estate instead. Brixton has fallen foul to that. Yet at the same time, really cool things happen. But sometimes what we call gentrification can be a cool thing, for example Pop Brixton. It’s good for everyone, they employ people from the local community, their prices aren’t ridiculous, I see a lot of people coming from all over Brixton to go there. It’s not going to put the market out of business because those are flourishing still. That’s very much part of Brixton’s culture. I know what you’re saying: house prices are crazy. But that’s a whole different problem, and that’s about greed and capitalism, among other things.

What about the people who move into a “vibrant” area and then complain about noise?

If you take AIR Studios, in Hampstead, which is the main studio used by film orchestras, which gives a living to lots of musicians, they’ve been trying to shut it down for six months so they could extend the basement in the place next door: there was a campaign against that. It seems particularly with music that as soon as places are vulnerable with their licenses, they get shut down because an opportunist is waiting in the wings. That happens everywhere. You can’t change that unless you change fundamentally the way we think about politics and economics.

You’ve spoken before about the way the industry categorises different kinds of music. Has digital technology and streaming helped break down barriers? So that, for example, Spotify makes it easier for people to try different genres of music more easily than if they had to navigate the physical categorisation at Tower Records?

A lot of young musicians really struggle because there isn’t enough value attached to what they do

It’s very different, though the same companies which made money back then will still benefit the most. It’s interesting that you mention Tower Records and the whole world music issue – at the time I was nominated for the Mercury Award (2000) I went into Tower Records, and 11 of the 12 nominees were together under the Mercury section, and mine wasn’t. I asked where the Nitin Sawhney album was – I didn’t say I was Nitin Sawhney – and they sent me to the world music section. I pointed out that the Mercury section already had all kinds of genres mixed up, and the guy was confused, and sent me to world music again, then walked off. I ended up writing a letter to the head of Tower Records, and she ended up apologising to me at the Mercury Awards.

The idea of democratisation is powerful, and that can work for a lot of people. It’s changed lives for the better. But at the same time for me, it’s important to maintain a direct connection with my audience. I release albums direct to vinyl, and I create value by adding extra assets, by doing something special, creating a special event. For me, part of the experience of loving music as a kid was looking through the album sleeve, enjoying the cover and the whole process of buying an album, putting it on the record player, looking after it. You had a connection that felt more real. Now it feels like music is disposable and ubiquitous and immortal. Until the internet dies, the same piece of music can be shared endlessly, whereas when your record wore out there would be an emotional connection. The record lived a life, and that still has value.

The digital world has a value in democratising our perspective, and helping us access music in a more convenient way, but that doesn’t help us value it. That’s about education, and about the way our “leaders” are informing us about our priorities. Kids reflect those priorities. That’s why recently there was a Polish girl who hung herself because she felt persecuted, and I find it very difficult to believe that in some way Brexit wasn’t responsible for that. The way in which people speak, frame information, is what matters, and that’s true in music as well. It’s how people frame the information. It could be we can get access to music from across the world now. But do people do that? It depends how people respond to the information.

I didn’t know what Tracey Emin looked like, I just knew her as Tracey

You’ve commented on bias in the music industry before, and I was thinking of the comparison between the music industry and literature or comedy, where the British Asian influence is more prominent. Is there a problem specifically with music?

I know both of those worlds well, having worked with Salman Rushdie composing for Midnight’s Children, and in comedy, I was one of the writers on Goodness Gracious Me. With music, because of the way the industry was run, I think musicians have had a tough journey of it. I would say that a lot of young musicians really struggle because there isn’t enough value attached to what they do.

When we live in a demand-and-supply world – and the digital economy has amplified that model – it’s incompatible with the Malcolm Gladwell 10,000 hours argument, that musicians need that much time to build up their skills, so there ends up being a situation in which musicians feel bitter and resentful about the fact that they don’t get enough acknowledgement for the hours they’ve put in. There’s a disenfranchised young generation of artists who don’t know what to do with the talent they’ve built up. It’s about working with young artists and showing them there are other models, and you can interact with comedy, film, dance, and so on, which I always did. Now it’s a much more workable model than anything else.

NS: What about your own musical education? How did you fit it all in?

I started with all the classical piano grades, and was grade 8 piano by the time I was 11. Then I had flamenco lessons with Paco Peña in London, so I grew up playing classical and flamenco. I first got into jazz at the age of eight, and was playing in a quartet when I was 11. I played with the youth orchestra, then with a punk band, and a funk band as a teenager. I was in James Taylor’s quartet, and I played ACDC and Van Halen covers. I was the go-to session guy at school, but also in the Medway towns.

Ed Sheeran's a really nice bloke

I knew Billy Childish and Tracey Emin, I used to go for drinks with them in Rochester. I knew a lot of people in the artistic community there. At the time I just knew Emin as Tracey, who was Billy Childish’s girlfriend. We only met much later, by accident, at one of Paul McCartney’s parties. We talked for ages, but it was only afterwards when my girlfriend told me it was Tracey Emin. I didn’t know what Tracey Emin looked like, I just knew her as Tracey. It was a lovely shared moment. When we first met in Rochester everyone talked about Billy’s art, he was known as this incredible creative figure, involved in lots of different bands and projects. In one way, that Medway experience was very rooting for me, but I didn’t really find a way of embracing my heritage until I left that area, and started listening to people like John McLaughlin more.

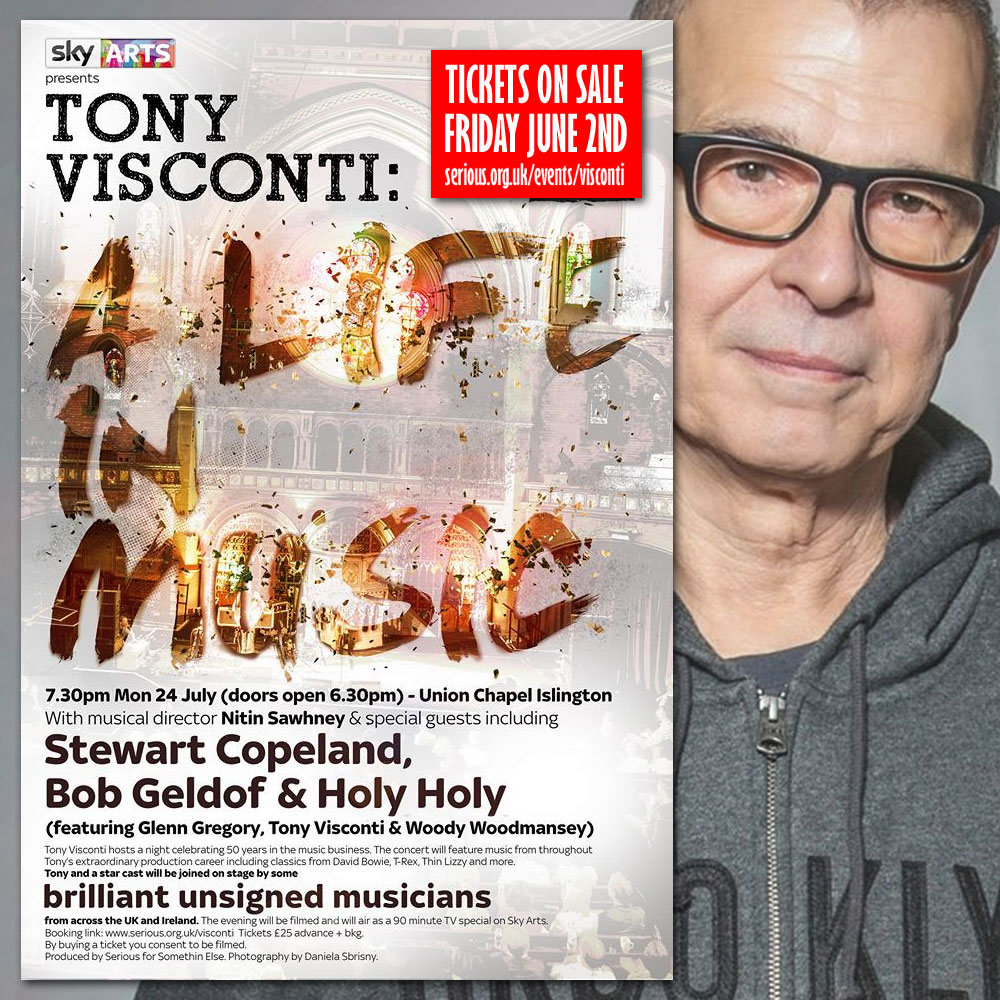

You do a lot of work in education, on the Access to Music programme, at LIPA, on Tony Visconti’s Sky Arts project A Life in Music, which gave a platform to many young performers – what else can we do for young musicians?

It’s great Tony put that programme together, so the young performers could play with so many experienced musicians. I was privileged to be musical director. It was good fun to be be playing Rebel Rebel with Tony, and Geldof singing. For the young musicians involved, it’s so hard to get started any other way now. Record companies don’t do the development deals that used to be ubiquitous. It’s much harder to get noticed for your talent, you have to have so much more going on with social media, just to get seen. I feel sad about that. It’s important that older artists take the time to give a bit of a leg up to people who may never get those experiences any other way.

I met Ed Sheeran on the Access to Music programme. I saw him when he was 16, and got to know him a bit then. We used to chat in the cafe at Matrix Studios. He seemed like a cool kid with a loop station, a singer-songwriter out there doing his thing. He still does in a lot of ways, it just so happens he’s got 65 million quid. It just seems every track he makes does really well. He’s a really nice bloke.

He has embraced the market approach to music wholeheartedly…

Totally. And he gets stick for it. The thing is that he has worked hard, and is a really good songwriter. He knows how to craft a track. It’s not necessarily what I’d do, but it’s what he does, and he does it well. Respect to him for that. He gets flak for that, but what do people want? I don’t know why people want to drag others down who’ve done well. I wouldn’t necessarily buy one of his records, but I respect the fact that that’s what he’s done, and he’s achieved it. That’s nothing to knock.

It does seem with some of Sheeran’s tracks that it’s not about heartfelt music, but market research...

Paul McCartney has still got that same hunger

You see, it makes me laugh, I could rip apart the fuckers who say this stuff quite easily. How much real, experimental music from other cultures, where people really put their life and soul into the music, do his critics really listen to? A lot of the people who knock him work in the same commercial world. It’s just resentment. Unless his critics are people with an immense and profound knowledge of world music – and if they are, why focus on Sheeran so much? – it’s just hypocrisy.

Where do you look for new music?

I go through the internet a lot, on YouTube, following links, I also look at what my interns are listening to, and I talk to young singers. I’ll do something else like my radio show at some point, looking at what’s out there. I’ve been listening to new music from Mumbai, and how informed, and sussed that music is. This is what I find exciting. Young people in India have all of the same reference points as we do in the West, but they’re also able to draw on their culture and heritage, and they find something new and fresh, with an angle no one’s heard before. That’s new and exciting music.

Having worked with, and become yourself, a big international name in music, what’s the star quality all these people – McCartney, Visconti, etc – have in common?

They’re very focused. They know what they want, and have a drive that means they see things through to the point of delivery. They deliver in a room, whatever they’re doing, they see it through. Paul McCartney has still got that same hunger, he’s still interested in pushing boundaries. When I first met him in the Nineties, he was doing the Fireman project with producer Youth, and he wanted me to remix a couple of tracks. It’s pretty out there. He came to my house and we used to hang out there. It was a completely different thing from what he was used to. He was really pushing himself. All those people do. For Geldof, it’s not necessarily always through music, but he still has that drive. You can see it in his face.

Do we listen to narcissistic lunatic fuckers?

When I met Stewart Copeland, he was bouncing up and down with excitement about a new band he was forming with Mark King from Level 42. You would think he was 20.

You’ve written for film, theatre, TV, games, dance. Is there a format you’re particularly excited about, where you’d like to see your music feature more?

I’ve just been working with virtual reality, on the Imaginarium with Andy Serkis (a performance-capture and next-generation storytelling studio). I’m really excited by the potential of augmented reality, which can superimpose images. Now there are new glasses that can beam images directly onto your retina. So you have an experience of seeing things in 3D in front of you. The possibilities of working with that, with music, with sound, are amazing. Binaural experiences too, such as Simon McBurney’s 2016 one-man show Encounter: it’s immersive but also philosophically challenging, it makes you question the nature of reality.

We’re almost moving toward a Matrixkind of reality that could be dystopian and dark, but it could be really exciting. It’s about how we build our reality. That, for me, is what I find interesting. What are the realities we choose to build, and who do we listen to? Do we listen to narcissistic lunatic fuckers who tell us that their perspective is the only perspective when they’re clearly talking bollocks, or do we listen to our own intuition? How do we know we can trust our intuition? Where does that guide us in terms of what music will mean in the future? What will reality mean? Everything is shifting. Virtual reality and augmented reality challenge us to think philosophically about who we are, and what we want from the world around us.

- Nitin Sawhney performs at The Globe August 21

- Sadler’s Wells’ new production of Dystopian Dream opens at the Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, on 29 September, and tours in France before transferring to London in 2018

- Nitin Sawhney composed the score for Andy Serkis’ film Breathe, which will open the London Film Festival in October

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Tom Grennan - Everywhere I Went Led Me To Where I Didn't Want To Be

British pop star's fourth exhibits ultra-pop oomph with mixed results

Album: Tom Grennan - Everywhere I Went Led Me To Where I Didn't Want To Be

British pop star's fourth exhibits ultra-pop oomph with mixed results

Album: Emma Smith - Bitter Orange

The award-winning jazz singer brings new life to some classic standards

Album: Emma Smith - Bitter Orange

The award-winning jazz singer brings new life to some classic standards

BBC Proms: Anoushka Shankar 'Chapters' review - somehow, it worked

Shankar's starry presence brings focus to this orchestral version

BBC Proms: Anoushka Shankar 'Chapters' review - somehow, it worked

Shankar's starry presence brings focus to this orchestral version

Album: Marissa Nadler - New Radiations

The Nashville-based singer-songwriter explores disconnection

Album: Marissa Nadler - New Radiations

The Nashville-based singer-songwriter explores disconnection

Album: Rise Against - Ricochet

Have the US punk veterans finally run out of road?

Album: Rise Against - Ricochet

Have the US punk veterans finally run out of road?

Add comment