theartsdesk in Karlovy Vary: Warm thermals at the International Film Festival | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Karlovy Vary: Warm thermals at the International Film Festival

theartsdesk in Karlovy Vary: Warm thermals at the International Film Festival

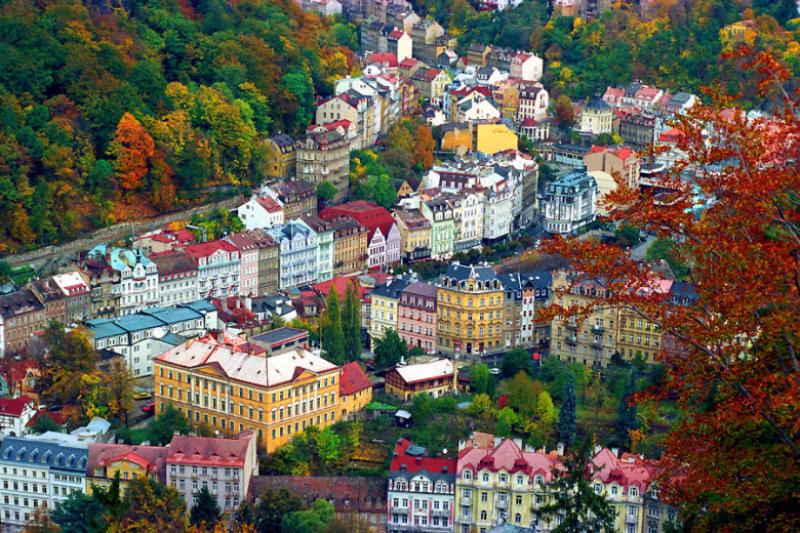

There's a low star count, but the Czech spa town is the best place to catch new cinema from Eastern Europe

The sleepy, picturesque Czech spa town of Karlovy Vary (formally Carlsbad) wakes up every July to the noisy bustle of one of Europe's oldest, largest and most vibrant film festivals.

Once you step out after a two-hour drive from Prague, the vibrant atmosphere hits you. What you hear is the constant clamorous babble of cinephile conversations among filmmakers, critics and the public in English, the lingua franca of the festival. For me, who’s been coming to the 52-year-old Karlovy Vary International Film Festival for about 10 years, the place offers a comforting sense of déjà vu. There’s the solid Soviet-style Thermal Hotel where most of the action takes place: terrace meetings, the press room, the video library, and screenings in the five small, rather pokey cinemas. Films are also shown at a few other cinemas around the town including at the opulent neo-baroque Grandhotel Pupp (pronounced “poop,” a source of hilarity for most childish newcomers.)

The spacious Grand Hall at the Thermal is where the red-carpet events take place. Karlovy Vary, which has no pretensions to being starry like Cannes or Venice, manages to attract a number of stars each year, mainly to hand them special awards. This year, the Crystal Globe for Outstanding Artistic Contribution to World Cinema was given to Ken Loach and Paul Laverty. The heavy and handsome Crystal Globe, given over the years mainly to performers, is the theme of a collection of self-mocking comic shorts, always shown before features.

The spacious Grand Hall at the Thermal is where the red-carpet events take place. Karlovy Vary, which has no pretensions to being starry like Cannes or Venice, manages to attract a number of stars each year, mainly to hand them special awards. This year, the Crystal Globe for Outstanding Artistic Contribution to World Cinema was given to Ken Loach and Paul Laverty. The heavy and handsome Crystal Globe, given over the years mainly to performers, is the theme of a collection of self-mocking comic shorts, always shown before features.

They include Harvey Keitel in pain after having dropped the award on his foot (“Shit happens,” he mumbles ruefully), Miloš Forman using it to crush pills he has to take, Andy Garcia breaking open the front door of a house with it when he’s lost his keys, and a disgruntled John Malkovich, in the back of a cab in New York on his return from Karlovy Vary, being asked by the Indian taxi driver what the award was for. When he says it was a Lifetime Achievement Award, the driver just says, “Oh!”. Malkovich replies, “What do you mean ’Oh!’ Oh, it’s long overdue? Oh you deserved it? Oh, your fucking career is over?” Maybe next year we’ll have Loach hitting Laverty over the head with the Crystal Globe.The President’s Awards were presented to Casey Affleck, who was there to introduce a screening of the haunting A Ghost Story (with Rooney Mara, pictured above) and Uma Thurman. The President’s Award, according to the festival organisers, is presented "to directors and producers who have contributed in a fundamental way to the development of contemporary world cinema". Hmm!

But being at the crossroads of East and West Europe, Karlovy Vary is the place to catch up on the best of Eastern European cinema. Usually the strongest section is East of the West with a number of interesting recent Czech, Slovak, Russian, Polish, Romanian, Estonian, Turkish, Ukrainian and Georgian films. Falling (Strimholov) is an Ukrainian feature film debut (pictured above) directed by Marina Stepanska. This low-key, nocturnal drama follows a young man, sensitively played by Andriy Seletsky, having been in a rehab centre for alcoholism and drug addiction, trying to adapt to a normal existence. The title is a rather obvious metaphor illustrated when he teaches his self-disparaging girlfriend to continue to get back on a bicycle no matter how many times she falls off. But the film is a timely reflection of post-Maidan malaise.

Falling (Strimholov) is an Ukrainian feature film debut (pictured above) directed by Marina Stepanska. This low-key, nocturnal drama follows a young man, sensitively played by Andriy Seletsky, having been in a rehab centre for alcoholism and drug addiction, trying to adapt to a normal existence. The title is a rather obvious metaphor illustrated when he teaches his self-disparaging girlfriend to continue to get back on a bicycle no matter how many times she falls off. But the film is a timely reflection of post-Maidan malaise.

Marita by Cristi Iftime is another feature film debut. Cristi, of the next generation after the Romanian New Wave, now at low tide, uses much of the style of his prestigious predecessors – stark improvisatory realism, long takes and no non-diegetic music. Like many Romanian movies, Marita is a family drama, almost a road movie, about an irresponsible elderly man trying to reconnect with his three adult sons, going to see them in the eponymous old car. The film is intriguing up to a long dinner scene in which the four men, all drinking heavily, start telling jokes, greeted with much laughter. Alas, not by the non-Romanian speaking audience, because they are all completely lost in translation. More (Daha), by Onur Saylak, is a powerful, topical study of human trafficking (pictured above) in a small coastal town in Turkey. It shows the brutalising effect on those who smuggle refugees from the Middle East, especially on a 14-year-old boy, who wants to study but is forced into the dirty job by his despotic father. Very well played and directed, the film becomes rather exploitative in using the refugees as an element in a crime thriller.

More (Daha), by Onur Saylak, is a powerful, topical study of human trafficking (pictured above) in a small coastal town in Turkey. It shows the brutalising effect on those who smuggle refugees from the Middle East, especially on a 14-year-old boy, who wants to study but is forced into the dirty job by his despotic father. Very well played and directed, the film becomes rather exploitative in using the refugees as an element in a crime thriller.

Khibula follows the success of George Ovashvili’s impressive Corn Island a few years ago. Set in 1991, against an imposing, beautifully shot Caucasus, it tells the true story of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the first democratically elected president of the newly independent Georgia, who was ousted by a military coup a few months later. Ovashvili manages to avoid monotony despite the film being a series of similar sequences as the ex-president, with a bunch of loyal followers, moves from place to place in the mountains, avoiding capture.

The Little Crusader (Křižáček), and coincidentally winner of the Grand Prix (pictured below), was the Czech Republic’s contribution to the main competition. Self-consciously arty at times, yet captivatingly shot, it conjures up the days of the Crusades, where a knight father is on a quest to find his young son who has joined the Crusades. The director, Václav Kadrnka, is certainly talented, creating a period epic on a low budget.

This year was a relatively rich bunch, although as with all festivals where only world premieres must be shown in the main competition, the highest praise is often “Not bad”. However, it says something about contemporary cinema that the real treasures are to be found in the archive and retrospective sections. For example, there was Ján Kadár’s 1965 classic The Shop on Main Street, digitally restored by the leading Czech post-production house UPP and sound studio Soundsquare.

The thought of three hours on an uncomfortable seat watching A Journey Through French Cinema was not something I was looking forward to; after all, I consider myself somewhat of an expert on the subject. But time flew by in the company of the genial Bertrand Tavernier, expounding on his personal tastes. While treating the audience as equals, never catering down, he cast light on a multitude of film extracts, some even unknown to me.

The thought of three hours on an uncomfortable seat watching A Journey Through French Cinema was not something I was looking forward to; after all, I consider myself somewhat of an expert on the subject. But time flew by in the company of the genial Bertrand Tavernier, expounding on his personal tastes. While treating the audience as equals, never catering down, he cast light on a multitude of film extracts, some even unknown to me.

Among the best films hors concours were particular delights for the cinephile: absorbing documentaries on the recently deceased Andrzej Wajda and Abbas Kiarostami as well as a 1975 film by Kaneto Shindô on Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director as a complement to the screening of 10 of Mizoguchi’s masterpieces. These were as stimulating as Karlovy Vary’s hot springs.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Add comment