Chris Patten: First Confession - A Sort of Memoir review - remembrances of government and power | reviews, news & interviews

Chris Patten: First Confession - A Sort of Memoir review - remembrances of government and power

Chris Patten: First Confession - A Sort of Memoir review - remembrances of government and power

Reflections of a Tory grandee

It’s 25 years since Chris Patten lost his seat as Conservative MP for Bath. The 1992 election was called by an embattled prime minister, bruised by the Maastricht Treaty (remember “the bastards”?). Neil Kinnock had been expected to win, Labour ahead in the polls until the last.

He felt “sick at the humiliation” but a consolation prize was soon offered by John Major, one that came with a fancy dress costume and innumerable baubles and flunkies: the last British governorship of Hong Kong before it was handed back to the Chinese. Patten accepted, “after talking to Lavender”, whose career at the bar was put on hold. It was a glamorous posting though he had to put up with the carping of former PM Edward Heath, who “denounced” him even as he stayed under the Governor’s roof.

First Confession is a well-written book, mercifully not a linear trudge through life and career but an examining of it in a dozen thematic chapters, the first and last dealing in some depth with Patten’s Catholic faith. Many old-fashioned Catholics would argue that Catholicism, and Christianity in general, is incompatible with the central tenets of modern-day Conservatism: in 2014, think-tank Theos found that Catholics were the most left-wing of Christian groups and more pro-welfare than Anglicans. Iain Duncan-Smith, another Catholic Tory, surely worships a vengeful God.

Patten spends some pages explaining why – on returning from his post-Oxford sojourn in the United States on a Coolidge Fellowship, something of an extended jolly which included work on John Lindsay’s campaign for the New York mayoralty – he decided to hitch his wagon to the Conservatives. Robert Peel, Harold Macmillan and Rab Butler were the principal reasons and, on the Labour side, Harold Wilson, whom he disparages. Yet he notes that “the best things to emerge” from the 1960s and ‘70s were “the Open University, Roy Jenkins’s reforms at the Home Office, avoiding getting involved in the Vietnam War and the joining the European Common Market”. Of those, Wilson can take credit for the first three. Theresa May is currently destroying the fourth.

Patten spends some pages explaining why – on returning from his post-Oxford sojourn in the United States on a Coolidge Fellowship, something of an extended jolly which included work on John Lindsay’s campaign for the New York mayoralty – he decided to hitch his wagon to the Conservatives. Robert Peel, Harold Macmillan and Rab Butler were the principal reasons and, on the Labour side, Harold Wilson, whom he disparages. Yet he notes that “the best things to emerge” from the 1960s and ‘70s were “the Open University, Roy Jenkins’s reforms at the Home Office, avoiding getting involved in the Vietnam War and the joining the European Common Market”. Of those, Wilson can take credit for the first three. Theresa May is currently destroying the fourth.

Perhaps in another time Patten would have chosen differently, though one suspects not for he appears to feel that if he, a lower-middle-class boy from Greenford, could make it then so can anyone. He knows he was lucky, admits to having been a bumptious and smug youngster (a scholarship to St Benedict’s, another to Balliol) and acknowledges that today “inequality is too high in financial terms”. He acknowledges too that his unbroken ascent up the ladder owes much to Oxford contacts but suggests, “without undue vanity”, that it was his performance that counted. That may be so, but it’s not always the case. “We do have an establishment in Britain… who run much of the country and many of its institutions” – though that's surely better than France, where the top jobs are secured by those who survive the “fiercesome examination culture”. Professionals who know what they are doing! These days, Britain can’t even manage inspired amateurs.

Patten provides an engaging read, a trip down memory lane for those old enough to remember the three-day week and the poll tax riots, but inevitably leaves questions unanswered. Did Mo Mowlam ask him to chair the Independent Commission on Policing in Northern Ireland because he was Catholic or despite it? (He had served in the Province as a junior minister in the days when it was a problem to be managed rather than solved.) And in his brief tenure as Chairman of the BBC Trust, was he perhaps less than fastidious querying Newsnight’s evidence about Lord McAlpine’s alleged involvement in a paedophile ring because he’d heard that McAlpine had cheered his 1992 defeat? There’s no Catholic self-examination – only a quick exit from the BBC on grounds of heart surgery. The fancy dress of his Oxford Chancellorship seems more alluring.

Of the PMs he served as an MP, he likes and admires Major unreservedly (“a brilliant negotiator… one of the most decent people ever to lead the Conservative Party”) and grudgingly admires Thatcher. Heath was conniving and self-serving, backing Alec Douglas-Home over Butler because he guessed that meant the path to No 10 would soon reopen. An anecdote is horribly revealing: arriving at Heath’s Albany home one Saturday morning with Ronnie Millar to write a party political broadcast, Patten was kept waiting an hour. Eventually, “Heath appeared in a vast kimono-style dressing gown… like a character from a Savoy opera. No apology, just a brusque ‘Right, care and compassion this morning, I believe’. At 1pm, his housekeeper arrived bearing a solitary lobster and a half-bottle of Chablis. 'Have you chaps eaten yet?’ ‘No,’ we replied, enthusiasm mounting. ‘You must be jolly hungry then,’ he replied, munching and sipping on.”

Of May and David Cameron, there’s only passing mention: the book went to press as the election was called. A pity because, though his Europhile preferences are clear, it would have been good to read a full exegesis of the Tory predicament by that now rare beast – a cerebral Conservative.

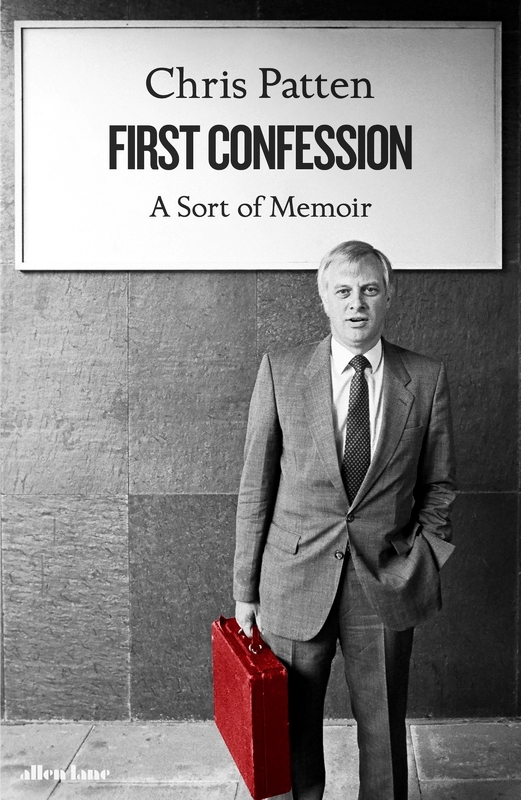

- First Confession: A Sort of Memoir by Chris Patten (Allen Lane, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

- Liz Thomson's website

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Add comment