Tristan und Isolde, Longborough Festival | reviews, news & interviews

Tristan und Isolde, Longborough Festival

Tristan und Isolde, Longborough Festival

Wagner benefits as usual from the intimacy of Longborough's converted barn theatre

The Longborough Festival was started, essentially, to perform Wagner, and Wagner is still what it does best. This revival of Carmen Jakobi’s production of Tristan und Isolde is the strongest argument imaginable for small-theatre Wagner.

Isolde is a passionate young girl with a manipulative streak. But what Wagnerian soprano ever troubles to convey such mundane intricacies? At Longborough Lee Bissett does so, and with enormous intelligence and conviction. Not only does she sing with power and control, but from the start she creates, through bodily gesture and mobile facial expression, a vivid image of a young woman who is finding it hard to decide whether she hates or is in love with the man who is escorting her to marry the King of Cornwall. And once she has made up her mind, she conveys equally well the rapture and intensity, and the inevitable doom, of the love in question.

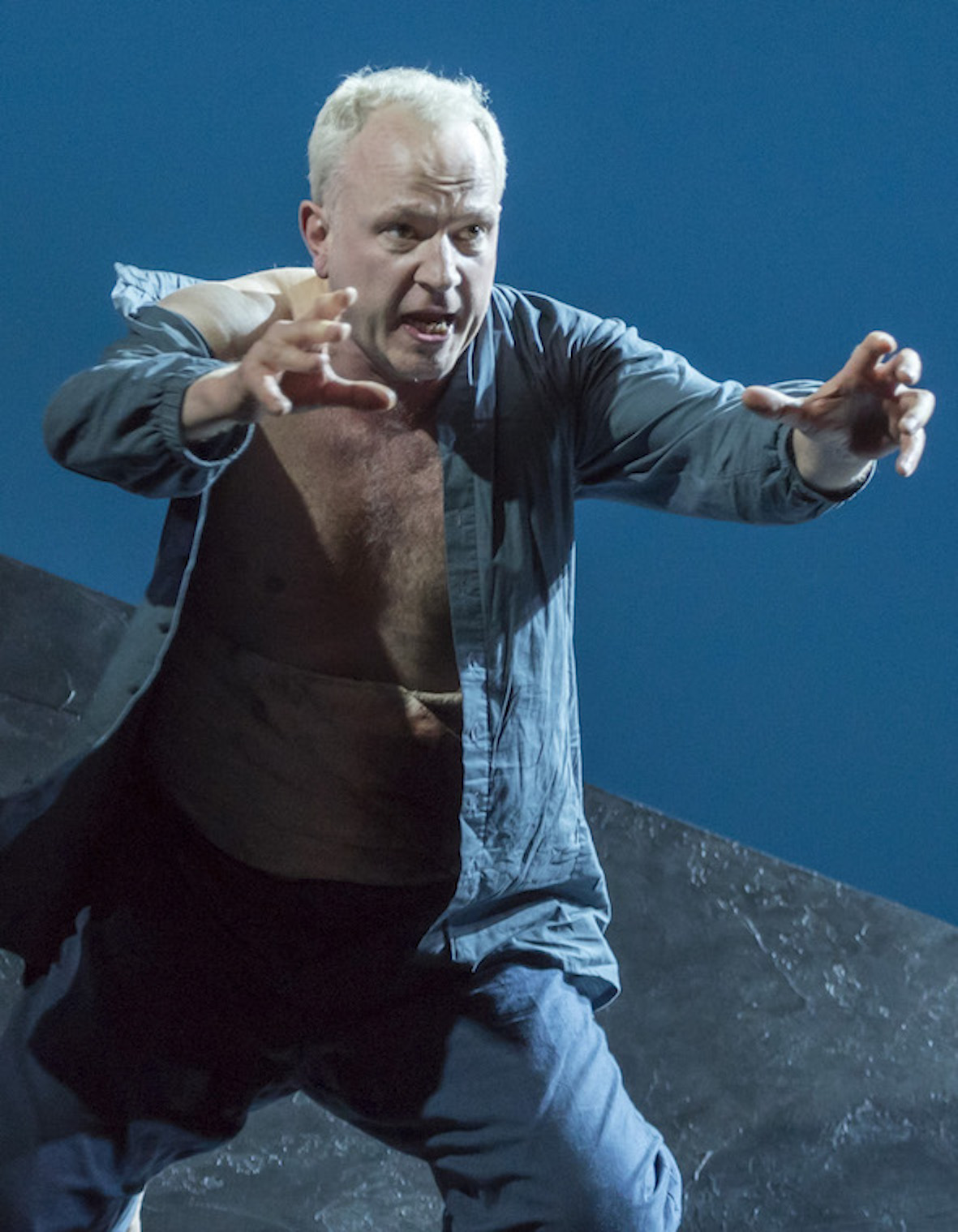

Peter Wedd (pictured right) is likewise more volatile from the start than the usual impassive, courteous delegate (his initial “Was ist? Isolde?” had one almost jumping out of one’s seat). His is a Tristan palpably on the verge of a forbidden love, and petrified of the fact. Out of this portrait there develops a nearly unbearable intensity in the subsequent acts, an intensity of a kind perhaps only really achievable in an intimate theatre. The second act love duet is almost embarrassing in its proximity, as if one were eavesdropping on something too personal for public display. And Wedd’s third act delirium, magnificently sung, has an immediacy I’ve rarely experienced in this often wearisome monologue.

Peter Wedd (pictured right) is likewise more volatile from the start than the usual impassive, courteous delegate (his initial “Was ist? Isolde?” had one almost jumping out of one’s seat). His is a Tristan palpably on the verge of a forbidden love, and petrified of the fact. Out of this portrait there develops a nearly unbearable intensity in the subsequent acts, an intensity of a kind perhaps only really achievable in an intimate theatre. The second act love duet is almost embarrassing in its proximity, as if one were eavesdropping on something too personal for public display. And Wedd’s third act delirium, magnificently sung, has an immediacy I’ve rarely experienced in this often wearisome monologue.

The revival is well worth seeing, if you can cadge a ticket, just for this duo: marvellous character drama as well as great singing. But the cast as a whole has few weaknesses. Harriet Williams is a beautiful, touching Brangaene, a perfect foil to Bissett’s vengeful Isolde of the first act, and lovely offstage from her tower in the love duet; Stuart Pendred repeats his sturdy Kurwenal from the original production. Only Geoffrey Moses’s King Mark disappoints, too elderly-looking even for this aging widower, and inclined to hang below the note. Stephen Rooke (Melot), Sam Furness (Shepherd), and Adam Green (Helmsman) are all excellent.

Anthony Negus goes from strength to strength in his mastery of the sweep and scale of Wagner’s discourse, but I’ve heard more reliable playing from this orchestra. There were tentative moments in the prelude, and the hunting horns in Act 2 were maybe a shade too realistically alfresco. But these are teething troubles. Jakobi has mercifully got rid of the dancing doppelgangers and the onstage bass clarinettist of the original production, though I could do without Wedd’s vision of Isolde (new, I think) in the monologue, which weakens the effect of her actual entrance before the Liebestod. Kimie Nakano’s set designs, simple but atmospheric, and exquisitely lit by Ben Ormerod, are a joy as before.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Add comment