theartsdesk Q&A: Soprano Elizabeth Watts | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Soprano Elizabeth Watts

theartsdesk Q&A: Soprano Elizabeth Watts

Heading toward major lyric roles, the singer discusses her love for Alessandro Scarlatti

Not many people write conspicuously brilliant tweets, but Elizabeth Watts is someone who does. Working on the most demanding aria on her stunning new CD of operatic numbers and cantatas by the lesser-known of the two Scarlattis, father Alessandro rather than son Domenico, she tweeted: “Good news – I can sing 88 notes without a breath. Bad news – Scarlatti wrote 89.”

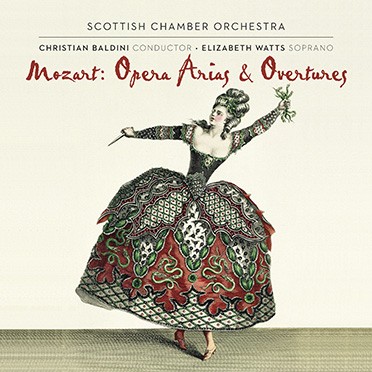

The sheer hard work behind that achievement, which Watts discusses below, reminds one that the best singing isn’t something that’s just a gift. And when she went to the Royal College of Music as a postgrad student at the age of 21, having gained a first degree in archaeology, she did indeed work very hard indeed. She could do the bright soubrette – “all tits and teeth”, as she told a PR – and rather stole the show as gaoler’s daughter Marzelline in a mostly very dull Royal Opera Fidelio in 2011. But 10 years after training, the voice is richer and darker: I was amazed by the sheer refulgence of her part in the Poulenc Gloria at Southwark Cathedral, and then by the intensity of many of her Mozart heroines on a disc of overtures and arias we chose as CD of the Month in the BBC Music Magazine. Meeting in a pub near Waterloo between her rehearsals for Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse, we started with that recording.

DAVID NICE I love the Mozart disc and the way you do the recits, that attack on “carnefice spietati”[“ruthless butchers”, or “Padre, germani, addio” from Idomeneo]. My perception, and it may not be yours, is that you’ve been a lightish lyric soprano and now you’re on the cusp of moving into something bigger, your Fiordiligi was tremendous, and I can even imagine your Donna Anna on stage.

DAVID NICE I love the Mozart disc and the way you do the recits, that attack on “carnefice spietati”[“ruthless butchers”, or “Padre, germani, addio” from Idomeneo]. My perception, and it may not be yours, is that you’ve been a lightish lyric soprano and now you’re on the cusp of moving into something bigger, your Fiordiligi was tremendous, and I can even imagine your Donna Anna on stage.

ELIZABETH WATTS Maybe, one day, who knows? I’m keen not to move too quickly into bigger lyric repertoire. I’m singing my first Countess [in Le nozze di Figaro] at WNO in the Spring, and taking it gently. But definitely my voice is going that way.

You mentioned Mozart’s Countess, and I’m reminded of Strauss’s Countess in Capriccio because the first time its Moonlight Music appears is in the satirical song-cycle Krämerspiegel [“Shopkeeper’s Mirror”]. It surprised me that you recorded that with Roger Vignoles, partly because I’d only ever heard a baritone sing the cycle.

They were written for a soprano.

Yet maybe there aren’t so many sopranos around with a sense of humour, which you certainly have?

Oh, they’re wonderful songs, so full of in-jokes about publishers, so you’ve got to do your homework. Some are incredibly rude. In one of the songs Strauss’s collaborator Alfred Kerr writes that the hero’s adversaries provoke him to the oath of Gotz von Berlichingen, a reference to a Goethe play in which that character says of the Emperor and his troops, “he can kiss my arse”.

But the public wouldn’t get a lot of that, would it?

Only the quotations like the one when he refers to Till Eulenspiegel, it’s very cleverly woven in. And then you get that Moonlight Music again, which I think is Strauss saying, “This is what you could have if you paid me properly”.

Any there any Strauss roles on the cards yet?

So far, they’ve not come my way. I’d love to have sung Sophie [in Der Rosenkavalier], it’s probably passed me by now.

What abouot Zdenka in Arabella [the sister who’s dressed up as a boy]?

I’m probably physically a bit curvy for Zdenka. I’m unlikely to be cast for that.

The Krämerspiegel made it clear that you’re interested in more unusual repertoire. Was the Alessandro Scarlatti disc [warmly reviewed by Graham Rickson] proposed to you?

The Krämerspiegel made it clear that you’re interested in more unusual repertoire. Was the Alessandro Scarlatti disc [warmly reviewed by Graham Rickson] proposed to you?

No, it was all my idea. When I was at music college I was looking at music for a competition, and I told my teacher I wanted to do something a bit more unusual. She said, have a look at this aria, “Ergiti’ [from Scipione nelle Spagne], and I quite liked it, and I thought this is good music. I’d seen Alessandro Scarlatti in the Arie Antiche book, I thought, how’s this orchestrated, what’s it like in context, there must be more good Scarlatti; I had a bit of a listen and thought, he’s quite a good composer, but nobody ever does him. And I was doing a concert with the English Concert and I thought, why not just find a load of Scarlatti arias for it, that was about four years ago. Then someone from Harmonia Mundi came along and said we should record this, it was just a question of finding the right timings…All my crackpot idea. Couldn’t have done it without Laurence Cummings [the conductor on the recording].

So back in your college days, you did sing the “Ergiti” aria?

I did it in competition, yes, for the Royal Overseas League.

And did you win that?

The vocal section, yes; I can’t remember which round it was in. But the impression remained. I decided to get out every score I could find of Alessandro Scarlatti.

Was that difficult?

Westminster Music Library is a wonderful place. Laurence and I went through quite a lot of the opera scores, and I listened to everything I could find on YouTube and Spotify, whatever was out there. There weren’t so many of the complete operas, actually. Mitridate Eupatore has been performed. I came across that initially reading biogs saying this is his masterpiece, but there was no recording, just a few snippets on YouTube of Joan Sutherland singing some ‘50s thing with the most fascinating orchestration but not entirely authentic.

So I was trying to find a score and I’d done this first round of Scarlatti, and in preparation for that I did a concert with Norwich Baroque, and [countertenor] Michael Chance was there, and I said I’m trying to find this score of Mitridate Eupatore, and he said, “I did it, with Rene Jacobs, I’ll lend you the score”. So I had a look through and there’s the aria. The very florid one, “Turbido irato”, that I found in Westminster Music Library, annoyingly someone recorded it in the interim, so it’s not the first recording, but I think I’m the first to do the run in one breath. That’s not pasted together, that is real. (Pictured below, Watts as Mandane in Arne's Artaxerxes, image by C Smith)

You have incredible breath control, it seems natural.

You have incredible breath control, it seems natural.

No-oo, it’s hard work. I worked with a candle on that phrase, like the castrati did, not allowing the flame to flicker, trying to get total control; I had a breath coach in Amsterdam helping me to work on that, as well as my vocal coach. I just practised and practised and practised. I bet even my neighbours could sing that run, they suffered it a lot. It really was hours and hours and hours – and more hours. I did get there in the end. In fact I ended up going for longer than I needed to, I’d done a few takes in one, and I said, look, I’m going to really go for it and see if I can go into the next phrase, and I did it and that’s what you’ve got on the disc. It actually goes on into the next phrase. So it’s probably 92 notes rather than 89.

There are also some very gentle and internalised arias…

I love that one with the strings, “A questo nuovo affanno”, it’s come out really well. Alfonso [Leal del Ojo, principal viola of the English Concert] is just exquisite – well, all the strings are exquisite.

Is that the one with… [sings badly]

Yes, [sings well], the strings are so divine. And in the recitative accompagnato to the “Torbido” [also sings short phrases], that’s really good writing, takes it out of you – and [leader] Huw [Daniel] is amazing in that solo [in “Esci omai”], just fantastic.

You do dialogue with the orchestra, as every good soloist, vocal or instrumental should – but the trumpet and you [in “A battaglia”] are meant to be responding, duelling almost.

I wrote all these crackers ornaments, Laurence helped, but I’d put in extra bars – here, and the trumpet would continue, then I’d improvise, and Laurence would help me out a bit, so we’re very much a team on that. I tell you what other track I really like, when I first came across “Con voce festiva”, I said, do you know what it’s crying out for? A tambourine. I suggested it to Bobby [Robert Howes, the percussionist], and – this is what I love about musicians, he didn’t just arrive with a tambourine, he arrived with a big box of tambourines, gave me a history of them, we tried out a load of different tambourines until we found the right one for the job. It’s things like that I love. And “Dolce stimolo” I’d never done in concert so it had a different feel when we were recording it, and I improvised on the spot and thought, oh, this is nice, and we kept it in.

Next page: more on improvisation, other sopranos, teachers and experience

A friend of mine,. Deborah York, has been working on improvisations with her just singing settings of poetry which she’s setting to music on the spot, and a cornet player echoes what she does –

Oh, wow –

And it’s a wonderful thing. She thinks there must be even more freedom in all this.

Well, the separation between composer and performer only came about at the turn of the Baroque, and in Renaissance music there wasn’t such a division. Reading around, I found people can be a bit sniffy about it and think singers weren’t as learned as instrumentalists, but where did the whole improvisatory element come from, and why were they all so good at it? Because there was a tradition of singers being improvisers, is what I think.

It’s part of the musicality, isn’t it?

I think so.

It’s intuition, not necessarily intellect.

Well, I never studied music until I went to the RCM. I come a bit from the archaeologist’s perspective. It’s interesting to read people and think, they don’t realize they’re making this assumption and that assumption. Because a lot of my degree was involved in hermeneutics and the assumptions that you make about the past, so it’s interesting to come from that perspective. Anyway, my voice is getting bigger, so I’m moving away from this kind of repertoire, and I don’t want to lose all this improvisation, I love it [laughs].

It’s interesting, isn’t it, that the coloratura is the thing it’s most difficult to keep working if the voice gets bigger? (Pictured right: with Luca Pisaroni in Le nozze di Figaro at Santa Fe)

It’s interesting, isn’t it, that the coloratura is the thing it’s most difficult to keep working if the voice gets bigger? (Pictured right: with Luca Pisaroni in Le nozze di Figaro at Santa Fe)

I don’t know: you see, there are obviously some voices that were born to do it. I never had the kind of voice that could just do coloratura. Every fast note I’ve sung I’ve slaved over, so I think it’s the technique. One of the best people I know for coloratura is my friend Jen[nifer] Johnston, the mezzo; she’s got an enormous voice, but she’s got fabulous coloratura, you just do it.

I haven’t heard her in that rep.

Well, she doesn’t do so much, because she’s a whacking great mezzo, but she can do it. In Handel she was, like, that’s so easy, and I’d think, you bitch [laughs].

In Sutherland’s case the voice did get darker, and Bonynge wanted her to stick to that Donizetti/Bellini repertoire when she could have recorded, for example, the Empress in Die Frau ohne Schatten. In her final recording of Norma, it’s not the coloratura which impresses but the dramatic recitatives.

Well, listen to Callas – her coloratura’s excellent, she had a big voice. I think it’s voice and technique, there are some voices who just can’t do it, and of course there are limitations. I’ll never sing Brunnhilde, I couldn’t wipe someone’s ears out with my sound alone, and when I listen to Christine Brewer – I think, that sound, and yet the text is so clear.

You could sing Elsa and Eva, though, why not?

Maybe. Anyway, I think there’s a lump of people who can do coloratura, but if you don’t believe you can’t do it.

And should it be expression or fireworks, as Callas put it.

It’s the same with this Monteverdi – I’m singing Minerva. It’s a lot of fun. I put in some outrageous ornaments in, one or two of which have stayed in.

Did you have soprano idols early on? Was it Callas?

Callas, yes. And ever since I got the Janowitz/Karajan recording of Strauss’s Four Last Songs I’ve been a complete Janowitz fan. I think it’s one of the best discs of anything ever made, just the sheer beauty of the sound. I’ve got a lot of things on LP, I worked in a record shop.

I’ve just bought a turntable to resuscitate a lot of LPs that didn’t get transformed into CD.

And they’re certainly not going to now. I’m lucky to have recorded the Scarlatti in time.

And that’s exactly where you want the presentation and the notes, it’s a case where the format of the CD shouldn’t vanish.

Yes, it’s classic.

So did you collect in your youth, or do you still?

Well, people donate a lot of things to the Royal College, and they didn’t have space so they’d sell of a lot of their LPs while I was at college. So I got a lot of them from the RCM library when they were chucking them out. My dad was a sound engineer – he started at Decca, had his first proper job at their West Hampstead studios. And my first proper job was rehearsing there, because it’s now the ENO studios. He’s got fantastic ears, but technically he’s tone deaf. My husband did not believe my father could be tone deaf until he attempted to sing “Happy Birthday” – he had no clue if he was going up or down. But he’s got really incredible ears, and I was interested in sound from his perspective, and when I gave concerts dad would often record them.

So you have an archive…

Never to see the light of day, I hope.

Maybe in 20 years’ time people will want recordings of “The Young Elizabeth Watts”?

I sang on a recording with a girl’s choir, I did a solo on that, and that was definitely not my best take, I can tell you that much.

Now that we’ve got Julie Andrews in her teens singing “Je suis Titania” from Mignon…

Oh, really? Blimey. My first recording was aged six, when I did a solo in the Roger Jones musical Stargazers at my local church, and I did a lullaby called “Jesus, baby Jesus”. It’s surprisingly OK, actually. When I was about 10 I went around impersonating Pavarotti singing “Nessun dorma” at the World Cup. The first big solo I ever sang was in the Poulenc Gloria. Because when I was 17 we did it at school and I didn’t sing the solos for the performance, we got someone in, but I sang them in at rehearsals. Then there was a big girl's schools' gathering at the Albert Hall and I got to know some girls from another school and they were doing it and they said, would you like to come and do it for us? So I went and did it when I was 18.

And had you had lessons by then?

Yes, since I was 14, with a local teacher in Norwich, who’s actually now the curator of the Red House, Caroline Harding. She was a wonderful teacher, and Norwich is the best city in the world!

All those churches.

And 365 pubs. They say the city has a church for every week of the year and a pub for every day. So Caroline Harding opened my eyes and ears to so many things, gave me Schubert songs, amazing.

You did a lot of competitions like the Ferrier, which you won, and you’ve been the recipient of various awards.

They’ve definitely helped me, and the Borlotti-Buitoni Trust have supported me long term, since 2011. That’s important. I was a good singer 10 years ago (pictured left, publicity image for her debut Schubert disc) but I’m a much better singer now. I think it’s a shame that opera and singing as a whole is youth-obsessed, and there’s a move towards that in a lot of classical music. And it’s a shame really, because you learn so much all the time and your voice changes, and it’s great if you’re 21 and you’re the complete package, like Karita Mattila was when she won the first Cardiff Singer of the World competition. But If you only go for people who happen to be a finished package at that age you miss out on the people who need more time – and it’s not wrong to need more time to have your confidence boosted. You wouldn’t be having this Scarlatti disc if I hadn’t been able to pursue this career. It was nice to make a signature disc of Scarlatti, it shows off a lot of my strengths but it’s personally interesting.

They’ve definitely helped me, and the Borlotti-Buitoni Trust have supported me long term, since 2011. That’s important. I was a good singer 10 years ago (pictured left, publicity image for her debut Schubert disc) but I’m a much better singer now. I think it’s a shame that opera and singing as a whole is youth-obsessed, and there’s a move towards that in a lot of classical music. And it’s a shame really, because you learn so much all the time and your voice changes, and it’s great if you’re 21 and you’re the complete package, like Karita Mattila was when she won the first Cardiff Singer of the World competition. But If you only go for people who happen to be a finished package at that age you miss out on the people who need more time – and it’s not wrong to need more time to have your confidence boosted. You wouldn’t be having this Scarlatti disc if I hadn’t been able to pursue this career. It was nice to make a signature disc of Scarlatti, it shows off a lot of my strengths but it’s personally interesting.

And did stagecraft take a long time for you – did you always feel at ease on stage?

I always enjoyed being on stage, I did have to do a lot of work, my confidence had to grow and I had to learn a lot of things; music college was good for me, yoga was good, about kneeling on the breath. You learn all the while. Most people aren’t good as Andrew Shore the second they leave music college – I don’t know if Andrew Shore was as good as Andrew Shore, he probably was.

Were there any particular directors who switched the light on for you?

We had this director called William Relton who worked a lot with us at college in the Handel operas – he believed in me. But when you’re not as good as you might be at something, some people don’t see what you might be good at, they just see all the things that you’re not good at. I’ve always loved performing, I did a bit of acting at school, I wanted to be an actor when I was younger. I think that sort of thing and the archaeology make an interesting mix when you’re approaching a Baroque aria, when you haven’t done the whole opera; you’re bringing – say with a cantata – your whole life experience to it, they’re both useful disciplines to come from.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment