Risk, Turner Contemporary | reviews, news & interviews

Risk, Turner Contemporary

Risk, Turner Contemporary

An exhibition that interprets its theme far too widely, but there's still plenty to enjoy

Yves Klein staged a photo of himself, in November 1960, swallow-diving into the air from a first floor window, arms outstretched like a bird.

Why this fascination with artists who take risks in and for their art? In his book Man’s Rage for Chaos Morse Peckham argues that art provides an arena in which to experience risk at arm's length. The more uncertainty we face in real life, the more we need opportunities for the safe rehearsal of risk-taking, and art provides this important function.

Klein didn’t take physical risks, yet he is remembered as a pioneer who redefined the role of the artist. By focusing attention on what he did rather than made, he shifted the emphasis from product to process and became one of the first artists for whom the performance of a work was integral to the piece.

It doesn’t take a huge leap of imagination to get to the point where the performance is an end in itself, the only product being a record of it in photographs, drawings, videos or an installation. And changing the emphasis from a finite product to an open-ended process inevitably shifts attention to the riskier aspect of art-making – to uncertain outcomes.

It doesn’t take a huge leap of imagination to get to the point where the performance is an end in itself, the only product being a record of it in photographs, drawings, videos or an installation. And changing the emphasis from a finite product to an open-ended process inevitably shifts attention to the riskier aspect of art-making – to uncertain outcomes.

It is appropriate, then, that Leap into the Void (pictured right) features in Risk, an exhibition that explores our fascination with risk-taking and includes both objects and documentation; be prepared for a lot of films and videos. But the curators have broadened the remit to include uncertainty, chance, surprise, fear, provocation, role-playing and randomness, even including work that explores the concept of risk without the taking of any chances at all.

Juan delGado’s Sailing Out of Grain, 2012, for instance, is a very moving film about Helen Lister who, despite being paralysed from the neck down, sailed solo round Britain in 2009. When you have only your mouth to rely on to control the sails, the courage required to battle the elements is inestimable; making a film, on the other hand, requires very little.

Simon Faithfull’s film EZY1899: Reenactment for a Future Scenario, 2012 (main picture), shows a fire breaking out in an aircraft engine and quickly engulfing the fuselage and wing. This is no ordinary plane, though, but a dummy used to test fire extinguishers. The footage may be dramatic, but no-one is in danger – not even the man wandering about in a fire hazard suit monitoring results.

The title of the show is, in other words, somewhat spurious, and its application woolly. I could spend the rest of the review carping about what has been included and what left out, but since many interesting, enjoyable and important pieces are on show, better to forget the theme and enjoy the ride.

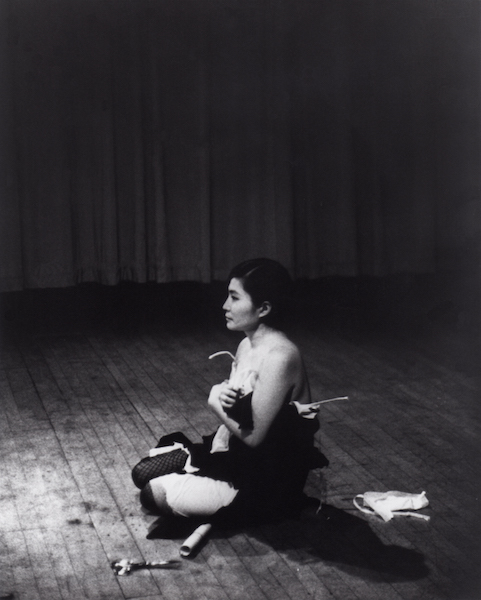

Yoko Ono risked real violence when she knelt on the floor and allowed people to cut off her clothing with tailor’s shears; anxiety registers all over her face as her clothes are gradually dismembered. By foregrounding the vulnerability of women, Cut Piece,1964 (pictured left) is one of the first truly feminist artworks.

Yoko Ono risked real violence when she knelt on the floor and allowed people to cut off her clothing with tailor’s shears; anxiety registers all over her face as her clothes are gradually dismembered. By foregrounding the vulnerability of women, Cut Piece,1964 (pictured left) is one of the first truly feminist artworks.

Marina Abramovič and Ulay staged many performances exploring the dynamics of their relationship. In Rest Energy, 1980, they face each other, Abramovič holding a bow and Ulay holding the string and an arrow pointing at her heart; had the arrow been released, she would have been seriously wounded. Microphones pick up their heartbeats as the minutes tick by and the tension mounts.

Carsten Höller’s swing is placed on the roof of the gallery, its frame gleaming red against the sky. The seat is invitingly empty – tempting you to experience the euphoria of kicking your legs up until you fly high over the courtyard. But access to the roof is denied, so your courage won’t be tested.

Frances Alÿs spent 10 years chasing tornadoes across the Mexican desert, braving dust clouds in order to reach the calm at the centre of the whirlwind (pictured below). Dutch artist Bas Jan Ader made absurdist films of himself falling off roof tops and plunging into canals, but in 1975 he actually died for his art. An experienced sailor, he set off in a four-metre boat hoping to break the world record for crossing the Atlantic in the smallest vessel. His boat was recovered a year later but his body was never found. On show is a photograph of a choir singing sea shanties that formed part of his farewell exhibition at a gallery in Los Angeles.

Numerous works made by enlisting the help of chance are also included. In 1984 American artist Chris Burden created a series of outdoor sculptures by dropping steel beams from a crane into soft cement, where they came to rest at awkward angles like a bunch of unruly teeth. Robert Morris’s elegant Wall Hanging (Tenture), 1970, is a length of heavy felt cut into horizontal bands and hung on the wall to allow gravity to determine its shape.

Peter Kennard’s anti-war posters are impressive examples of photomontage, but they have no place in an exhibition about risk-taking, since they address the power of propaganda rather than the threat of nuclear war. Nor does Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s The Way Things Go, 1987, but since it's the best artists’s video ever made, its inclusion is a delight. Set up in their studio like in a continuous line, an apparently unending series of absurd sculptural happenings demonstrates the principle of cause and effect. A paint can rolls down a makeshift slope and bumps into a precarious assemblage of studio tat that collapses and triggers the next encounter in which a nudge, a knock or spillage causes another makeshift structure to topple and another pot to fall or roll. Exploring the dual pleasures of destruction and construction, this sequence of brilliantly orchestrated mishaps provides 30 minutes of unadulterated pleasure. And no risks have been taken – apart from the possibility of the experiment going disastrously wrong and the studio blowing up or catching fire. Oh well, that’s life.

Peter Kennard’s anti-war posters are impressive examples of photomontage, but they have no place in an exhibition about risk-taking, since they address the power of propaganda rather than the threat of nuclear war. Nor does Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s The Way Things Go, 1987, but since it's the best artists’s video ever made, its inclusion is a delight. Set up in their studio like in a continuous line, an apparently unending series of absurd sculptural happenings demonstrates the principle of cause and effect. A paint can rolls down a makeshift slope and bumps into a precarious assemblage of studio tat that collapses and triggers the next encounter in which a nudge, a knock or spillage causes another makeshift structure to topple and another pot to fall or roll. Exploring the dual pleasures of destruction and construction, this sequence of brilliantly orchestrated mishaps provides 30 minutes of unadulterated pleasure. And no risks have been taken – apart from the possibility of the experiment going disastrously wrong and the studio blowing up or catching fire. Oh well, that’s life.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment