BBC Symphony Orchestra, Volkov, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Symphony Orchestra, Volkov, Barbican

BBC Symphony Orchestra, Volkov, Barbican

An unlikely but stimulating classical frame for a new work by Richard Ayres

This Barbican concert began with a Mendelssohn overture and ended with a Haydn symphony. But on stage were the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Ilan Volkov. What did you expect in between, a Mozart piano concerto? Not likely. Instead they gave the first performance of No.48 (night studio) by Richard Ayres.

The opening of No.48 was a characteristic Ayres refrain, a frantic merry-go-round of bells and piccolo alternating with earthy brass that brought the 20-minute piece to a yah-boo-sucks anti-closure. In the middle, a pocket primer to good old classical music, structured (if that’s quite the word) by a tape part that’s part German radio announcer, part Beckett radio play. Twenty-second sonatinas, symphonies and concertos come and go, each lugubriously announced (Allegro – Adagio – Scherzo) and punctuated by the click of a door latch, steps, a sigh.

Is No.48 a parody of our attention spans? Or of our tenacious attachment to art-culture and certainties that harden into prejudices? Is the orchestra in the room, misbehaving when our man has popped out? Or is it in his head? Ayres’s music is baffling, and it’s meant to be, but it’s also funny and unnerving, like Beckett, or indeed the art of Philip Guston which Ayres claimed was an inspiration for the piece. Guston was an inveterate lucubrant – hence the subtitle – and No.48 paints a picture in sound of a man alone, with only his thoughts for company. The speed at which it cuts between Austro-German clichés reminds us that we think faster than we listen.

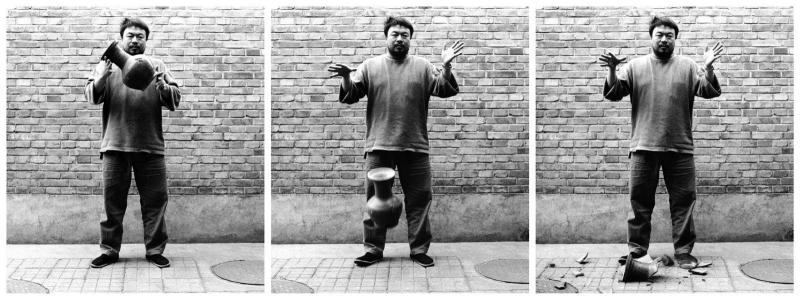

Listening for the continuity traced in classical narratives would miss the point. We bring different eyes to Rembrandt and Ai Wei Wei. Indeed Ayres and Ai share a weary fascination with the past and the weight of history which is captured by Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995, presently on display at the Royal Academy (and pictured above). However, Haydn got there first, as he always does. The slow movement of Symphony No.52 is to all intents athematic, no less than Ayres. Stuff happens, then it stops. On paper it looks far easier to play than Ayres’s copiously orchestrated candyfloss, but every phrase needs a direction and commitment that were lacking here. The tigerish ferocity of the first movement had its teeth extracted. The minuet was pretty, and pretty aimless.

Listening for the continuity traced in classical narratives would miss the point. We bring different eyes to Rembrandt and Ai Wei Wei. Indeed Ayres and Ai share a weary fascination with the past and the weight of history which is captured by Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995, presently on display at the Royal Academy (and pictured above). However, Haydn got there first, as he always does. The slow movement of Symphony No.52 is to all intents athematic, no less than Ayres. Stuff happens, then it stops. On paper it looks far easier to play than Ayres’s copiously orchestrated candyfloss, but every phrase needs a direction and commitment that were lacking here. The tigerish ferocity of the first movement had its teeth extracted. The minuet was pretty, and pretty aimless.

In the Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage which Mendelssohn wrote as a prototypical tone-poem after Goethe’s texts, the BBCSO made a much more convincing simalcrum of an early 19th-century orchestra than Haydn’s late-18th band, not through unpractised aping of manners such as pure tone and clipped phrasing but the transparency that naturally arises from their expertise in new music. Volkov revealed all the instrumental colours of Mendelssohn’s painterly eye and ear including a naturalistically piercing piccolo breeze and a piping naval trumpet trio to announce safe arrival in port. Beethoven’s vocal-orchestral setting of the same Goethe poems was far more generic, or so it seemed here, and the men of the BBC Singers returned after the interval for more aquatic Goethe – Schubert’s Song of the Spirits upon the Waters. It was, all in all, a typical Volkov programme, lacking polish but more than compensating with music to make you listen afresh.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Add comment