Listening, BALTIC 39, Hayward Touring | reviews, news & interviews

Listening, BALTIC 39, Hayward Touring

Listening, BALTIC 39, Hayward Touring

Tune in to Korean women who use special sounds to dive deep and trucks that change your radio station

Traditionally, art exhibitions have been about looking, but as more and more artists cross boundaries to engage with sound, touch and movement or to use film and video, work that is static and silent is becoming the exception rather than the rule.

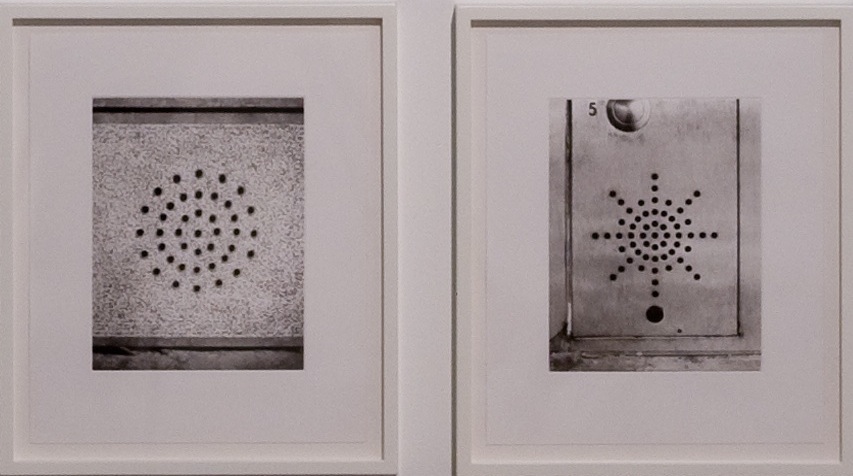

Curated by Sam Belinfante as a Hayward touring show, Listening focuses on the relationship between sight and sound. Ironically, the most resonant piece is totally silent. Sound Holes, 2007, by Christian Marclay (pictured below right) consists of photographs of the perforated metal plates indicating an intercom in a lift or beside a front door. Patterned in circles, clusters or starbursts, the radiating holes seem, almost comically, to broadcast the voices of the hidden speakers.

The most determinedly annoying piece is totally non-visual. Constructed according to the proportions of his bedroom, Prem Sahib’s closed chamber pulsates with party vibes so loud they penetrate to your bones. The visceral sensation is exciting yet sickening, just as the sound is an invitation but also a barrier; it's a deliberate, in-your-face irritant, like the noise emanating from a teenager’s bedroom or the boom box thundering inside a stretch limo hosting a private event.

The most determinedly annoying piece is totally non-visual. Constructed according to the proportions of his bedroom, Prem Sahib’s closed chamber pulsates with party vibes so loud they penetrate to your bones. The visceral sensation is exciting yet sickening, just as the sound is an invitation but also a barrier; it's a deliberate, in-your-face irritant, like the noise emanating from a teenager’s bedroom or the boom box thundering inside a stretch limo hosting a private event.

In this context, the silence offered by Haroon Mirza’s A Million cm3 of Quiet Space, 2013 (pictured below left) ought to be a blessing; but to get the benefit, you have to duck under the rim of his anechoic chamber, a head-sized box that blocks out all sound, and perch awkwardly on a block of stone. Once you’ve arrived, the sensation is rather unpleasant – partly because you are so low to the ground, partly because absolute silence feels stifling, but mostly because the carpet lining the box has a pungent aroma. I imagine it's a bit like being buried alive.

In his film Air Cushioned Ride, 2006, Anri Sala achieves the perfect match between sound and image. As he circles a parking lot full of trucks in Arizona, the baroque music playing on his car radio is interrupted by country and western. Far from being random, the switch happens at specific places, including every time he passes a truck with "Air Cushioned Ride'' written on the side. In a phenomenon known as “cross modulation”, the tall vehicles are blocking the radio waves from one station in favour of the other; to the viewer, it feels as though Sala’s space is being invaded by the truckers’ music, as he circles their patch.

In his film Air Cushioned Ride, 2006, Anri Sala achieves the perfect match between sound and image. As he circles a parking lot full of trucks in Arizona, the baroque music playing on his car radio is interrupted by country and western. Far from being random, the switch happens at specific places, including every time he passes a truck with "Air Cushioned Ride'' written on the side. In a phenomenon known as “cross modulation”, the tall vehicles are blocking the radio waves from one station in favour of the other; to the viewer, it feels as though Sala’s space is being invaded by the truckers’ music, as he circles their patch.

Some exhibits are better as ideas than actualities. Katie Paterson has recorded the moment a dying star is snuffed out. This momentous event results in little more than a grating sound, so brief it could easily be missed. When our earth finally dies, will its demise be similarly unremarkable? This sobering thought is, perhaps, the point.

Hannah Rickards has gone to great lengths to record a thunderclap, then to stretch and analyse the sound in order to recreate it with musicians before morphing it back into the sound of thunder. The net effect is neither convincing as a musical score nor as a natural phenomenon, so little seems to have been gained from all that effort.

For SeaWomen, 2012, Mikhail Karikis filmed the Haenyeo, women who dive for pearls off the South Korean island of Jeju. He was alerted to their presence by the high-pitched sound of the breathing technique they’ve developed, which allows them to descend 20 meters and resurface as many as 80 times in a day. The film pays tribute to a dying art, since the women are all elderly and their daughters choose less hazardous occupations.

While the Koreans are the real deal, Ragnar Kjartansson’s three nieces spent a day at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh (main picture) reclining on a plinth decked in turquoise satin so as to resemble the sea – pretending to be creatures of the waves. On film we see them combing their hair, gazing in mirrors, reading, strumming a guitar and singing a refrain from Allen Ginsberg’s poem Song. The mythical Sirens lured sailors onto the rocks with the beauty of their voices; if Kjartansson's ambition was to similarly seduce his audience, he fails since the girls behave more like bored teenagers on a sleep-over, than Muses of the lower world.

The sound quality of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s Cabin Fever, 2004, is so captivating that listening to the slamming car doors, hurried footsteps, distant doorbell, raised voices, shattering glass, gunshots, unanswered phone and buzzing flies one is propelled into the heart of a murder mystery. Housed in a box, the small, rather crummy woodland tableau accompanying the soundtrack is entirely redundant; the pictures conjured in one’s head are far more evocative.

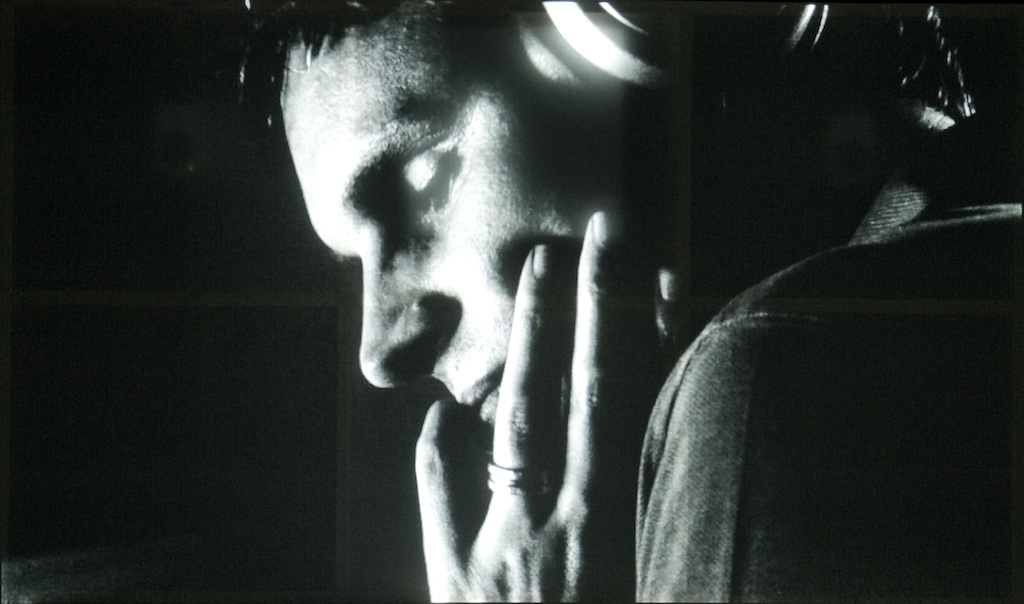

While Cardiff and Miller glory in the spatial potential of sound, Imogen Stidworthy seems to take us inside the head of Sacha van Loo, a man whose hearing is so acute he can determine a telephone number from its dial tones. Blind from birth, van Loo works for the Belgian Federal Police analysing wiretap recordings. Filmed in stark black and white to remind us of the darkness that envelops van Loo, Sacha, 2011, (pictured above) focuses on a close-up of his face. Witnessing his responses to a sound that, to most ears, is little more than a bleep, one becomes acutely aware of his enhanced ability to hear against most people’s propensity for looking. Watching a film has seldom felt more creepily voyeuristic – we are snooping, and so is he – or more poignant.

While Cardiff and Miller glory in the spatial potential of sound, Imogen Stidworthy seems to take us inside the head of Sacha van Loo, a man whose hearing is so acute he can determine a telephone number from its dial tones. Blind from birth, van Loo works for the Belgian Federal Police analysing wiretap recordings. Filmed in stark black and white to remind us of the darkness that envelops van Loo, Sacha, 2011, (pictured above) focuses on a close-up of his face. Witnessing his responses to a sound that, to most ears, is little more than a bleep, one becomes acutely aware of his enhanced ability to hear against most people’s propensity for looking. Watching a film has seldom felt more creepily voyeuristic – we are snooping, and so is he – or more poignant.

- Listening at BALTIC 39, Newcastle upon Tyne, until 11 January, then touring. For venues and dates see Hayward website

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment