Deutsche Börse Prize 2014, Photographers' Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Deutsche Börse Prize 2014, Photographers' Gallery

Deutsche Börse Prize 2014, Photographers' Gallery

A shortlist harking back to pre-digital image-making, and with one clear winner

Not so long ago, photographers were rejoicing in the freedom the digital revolution seemed to bring; unencumbered by the limitations of film, paper and darkroom practice, photography was suddenly liberated from the niggling pedantry of material constraints.

So it is in the cyclical nature of things that the photographers shortlisted for this year’s Deutsche Börse Prize all hark back, in some way, to pre-digital image-making, whether in their choice of equipment, technique or subject matter. Brett Rogers, director of the Photographers’ Gallery, argues that this illustrious prize plays a critical role in “reflecting the shifting boundaries of this mercurial medium”, and as such it is surely indicative of a renewed emphasis on the medium itself that all but one of the nominees reject the ubiquitous C-type print in favour of black and white.

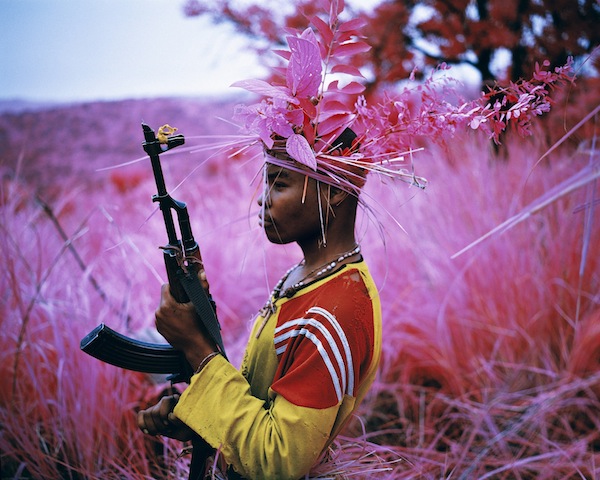

A decision to use a redundant film stock, developed by the US military in the 1940s, lies at the heart of Richard Mosse’s pictures of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Pictured above: Safe From Harm, 2012.) The film detects infra-red light from foliage, picking out the greens of the jungle in vivid magentas and so revealing camouflaged soldiers whose khaki uniforms and natural skin tones jar with this psychedelic version of the world. In Mosse’s images of a “disorienting, kaleidoscopic conflict”, the natural becomes alien while the sight of soldiers armed to the teeth is cast as normality. Their impact is undeniable, but his methods feel like gimmickry. As a retort to the conventions of war photography Mosse’s pictures are unconvincing.

A decision to use a redundant film stock, developed by the US military in the 1940s, lies at the heart of Richard Mosse’s pictures of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Pictured above: Safe From Harm, 2012.) The film detects infra-red light from foliage, picking out the greens of the jungle in vivid magentas and so revealing camouflaged soldiers whose khaki uniforms and natural skin tones jar with this psychedelic version of the world. In Mosse’s images of a “disorienting, kaleidoscopic conflict”, the natural becomes alien while the sight of soldiers armed to the teeth is cast as normality. Their impact is undeniable, but his methods feel like gimmickry. As a retort to the conventions of war photography Mosse’s pictures are unconvincing.

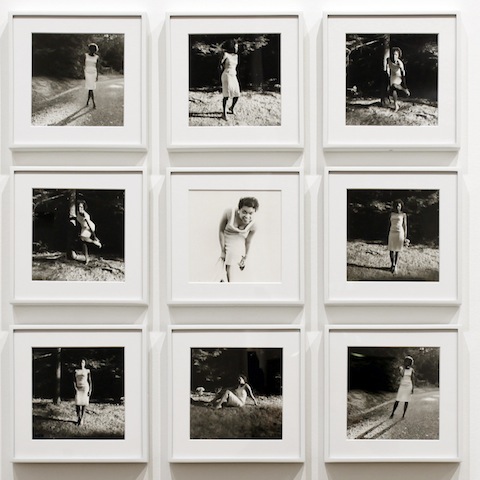

In her series, Summer ‘57/ Summer ’09, 2009 (pictured above: installation detail), Lorna Simpson has carefully reconstructed a collection of 1950s photographs bought secondhand. The pictures seem to be all of one woman adopting classic pin-up poses, and Simpson’s reconstructions, in which she takes on the role of this anonymous woman, are surprisingly hard to pick out from amongst the originals. There is something quite unsettling about the ease with which she has taken over this woman’s persona, but it suggests that since the Fifties little has changed in the way that women’s bodies are presented and viewed.

In her series, Summer ‘57/ Summer ’09, 2009 (pictured above: installation detail), Lorna Simpson has carefully reconstructed a collection of 1950s photographs bought secondhand. The pictures seem to be all of one woman adopting classic pin-up poses, and Simpson’s reconstructions, in which she takes on the role of this anonymous woman, are surprisingly hard to pick out from amongst the originals. There is something quite unsettling about the ease with which she has taken over this woman’s persona, but it suggests that since the Fifties little has changed in the way that women’s bodies are presented and viewed.

Like Simpson, Jochen Lempert invokes ideas about memory and record-keeping, and in so doing he exploits physical aspects of the medium to great effect. Lempert started out as a biologist, and his pictures, which often take the natural world as their subject, have the quality of working records. Unmounted and taped to the wall, Lempert has made a virtue of the way that prints on traditional, now virtually redundant, photographic papers curl at the edges, and the effect steeps his work in nostalgia. Lempert’s gaze is drawn to patterns, and many of his pictures show constellations, whether of stars, flying geese, swarms of insects or freckles on a shoulder. Moving between images of flowers, sand and raindrops, scale loses meaning, but the resulting abstraction serves to emphasise the patterns and similarities between things, so that the four white blobs and black squiggles of shadow in Untitled (four swans), 2006, look just like tadpoles (pictured above).

Like Simpson, Jochen Lempert invokes ideas about memory and record-keeping, and in so doing he exploits physical aspects of the medium to great effect. Lempert started out as a biologist, and his pictures, which often take the natural world as their subject, have the quality of working records. Unmounted and taped to the wall, Lempert has made a virtue of the way that prints on traditional, now virtually redundant, photographic papers curl at the edges, and the effect steeps his work in nostalgia. Lempert’s gaze is drawn to patterns, and many of his pictures show constellations, whether of stars, flying geese, swarms of insects or freckles on a shoulder. Moving between images of flowers, sand and raindrops, scale loses meaning, but the resulting abstraction serves to emphasise the patterns and similarities between things, so that the four white blobs and black squiggles of shadow in Untitled (four swans), 2006, look just like tadpoles (pictured above).

His interest in scale may have lead Lempert to experiment with photograms, the cameraless photographs made famous by Man Ray, in which objects are placed directly onto photosensitive paper and exposed to light. The technique means, of course, that solid objects are rendered in silhouette, and in his photogram, Four Frogs, 2010, the frogs appear bright white against black, creating a curiously artificial, schematic result.

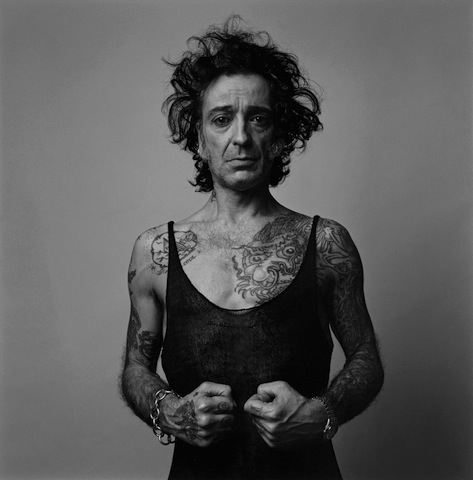

Beguiling as Lempert’s work is, it is the dangerous vitality of Alberto García-Alix’s pictures that steals the show. Documenting his own precarious life in the difficult years following the death of General Franco, the Spanish photographer has been nominated for his book Autorretrato/Selfportrait, 2013. The title seems a straightforward enough indication of subject matter, and yet the photographer himself is curiously elusive; García-Alix is often photographed from behind, and when, as in My feminine side, 2002 (pictured above), his gaze is directed squarely at the camera, the tongue-in-cheek title pulls the rug out from under our feet once again. A devotee of the Hasselblad camera with its trademark square format, García-Alix’s work is redolent of classic black and white photography, an image like My kitchen, 1982, bearing the compositional structure and control of a still-life.

Beguiling as Lempert’s work is, it is the dangerous vitality of Alberto García-Alix’s pictures that steals the show. Documenting his own precarious life in the difficult years following the death of General Franco, the Spanish photographer has been nominated for his book Autorretrato/Selfportrait, 2013. The title seems a straightforward enough indication of subject matter, and yet the photographer himself is curiously elusive; García-Alix is often photographed from behind, and when, as in My feminine side, 2002 (pictured above), his gaze is directed squarely at the camera, the tongue-in-cheek title pulls the rug out from under our feet once again. A devotee of the Hasselblad camera with its trademark square format, García-Alix’s work is redolent of classic black and white photography, an image like My kitchen, 1982, bearing the compositional structure and control of a still-life.

For pictures that linger over the sordid details of drug-addled excess, García-Alix’s work is strangely restrained, his sardonic juxtapositions of image and title punctuating often grim and disturbing images with verve and energy. His self-portraits direct our attention to a bigger narrative about the experiences of a whole generation shaking off the past and adjusting to new-found freedom and García-Alix shows the capacity of photography to combine poetry and documentary, to make compelling, insightful even, beautiful pictures that plumb the depths of human existence while retaining both honesty and dignity. For this reason he should win.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment