Valie Export and Friedl Kubelka, Richard Saltoun | reviews, news & interviews

Valie Export and Friedl Kubelka, Richard Saltoun

Valie Export and Friedl Kubelka, Richard Saltoun

Two women who were associated with the Viennese Actionists and who should be better known

The 1960s art scene in Vienna was dominated by Actionists such as Günther Brus, Otto Muehl and Herman Nitsch, who specialised in iconoclastic performances resembling pagan rituals. With women’s naked bodies being used either as raw material or an arena for sexually suggestive violations, they were often deeply misogynist.

Having exhibited the men, Richard Saltoun is now showing two of the women – Valie Export who defined herself as a Feminist Actionist, “an independent actor and creator, subject of her own history”, and photographer and film-maker, Friedl Kubelka who is scarcely known in this country.

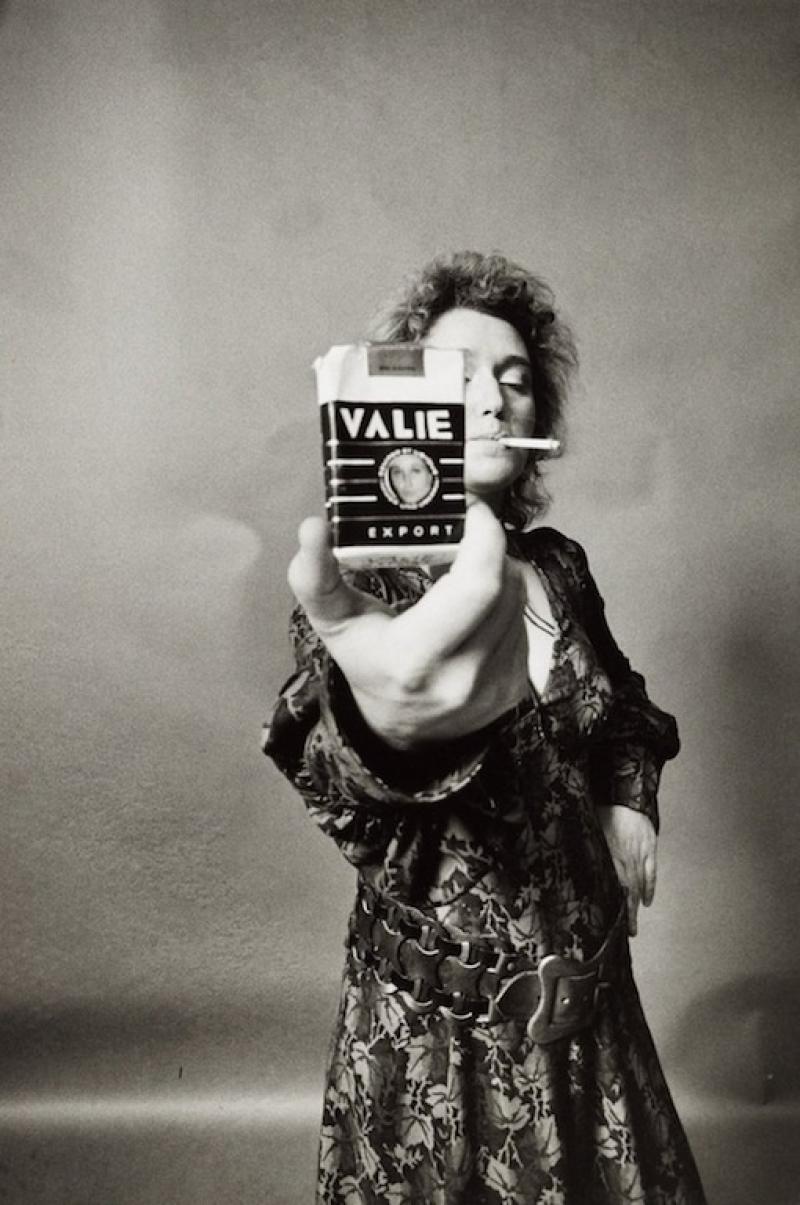

On show is Valie Export’s iconic self-portrait Smart/Export II, 1968/70 (main picture). To make herself visible in the male-dominated art world, Waltraud Höllinger adopted a new persona. Appropriating the name of her favourite brand of cigarettes, Smart Export, she inserted her face on the pack, changed Smart to Valie (the whole name is often capitalised) and surrounded her head by the motto "semper et ubique – immer und überall" (always and everywhere).

A black and white photograph shows her proffering the pack to camera; her wildly back-combed hair and the fag sticking out of her mouth make the image extremely confrontational, an in-your-face declaration of her intent to infiltrate masculine territory and be seen “always and everywhere”.

A black and white photograph shows her proffering the pack to camera; her wildly back-combed hair and the fag sticking out of her mouth make the image extremely confrontational, an in-your-face declaration of her intent to infiltrate masculine territory and be seen “always and everywhere”.

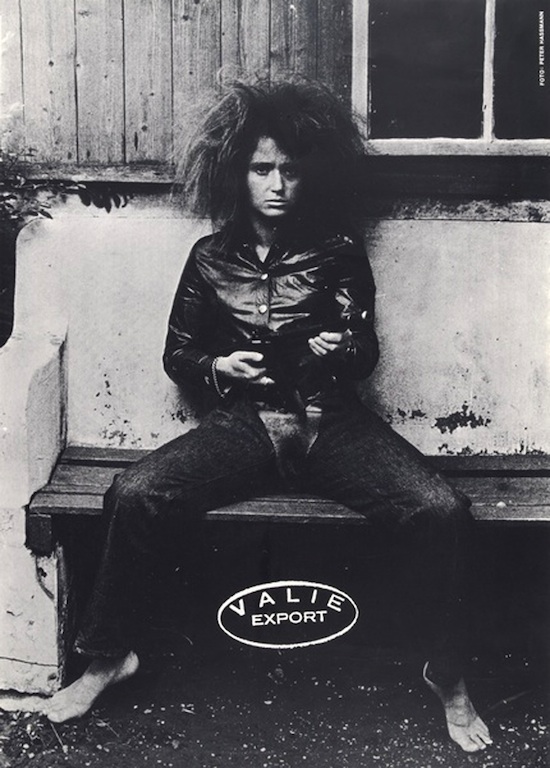

To that end she staged provocative performances such as Genital Panic (1969). Wearing jeans with the crotch cut out to expose her sex, she made her way through a film festival audience in Munich. While titillating shots of female flesh were deemed acceptable on screen, a close encounter with the real thing proved too much and many walked out.

On show is the accompanying silk screen print (pictured above right). Sitting legs apart, the artist establishes her credentials as a cultural terrorist, challenging men’s voyeuristic rights over women’s bodies by cradling a gun. In Freudian terms, the weapon might function as a fetish object compensating for her lack of a penis, but her masculine clothing and macho demeanour repudiate this phallocentric reading. This woman is unambiguously seizing power.

Three Bodies Configuration (1972/76) is a series of black and white photographs in which a woman tries to fit herself into the man-made environment. Lying on the pavement curled awkwardly round a corner, she appears absurdly out of place. Its a neat metaphor for the way women are obliged to inhabit social, political and legal structures created largely by and for men, which fail to accommodate their needs.

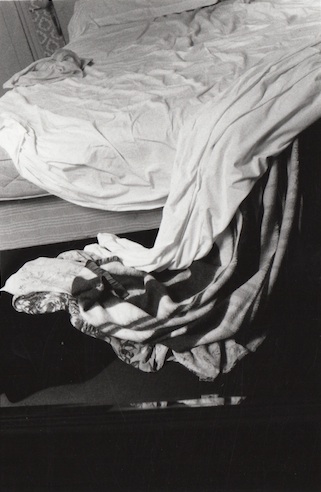

Friedl vom Gröller changed her name when she married film director Peter Kubelka. Voyage, 1974 (pictured left: Toulon 26.4.74 ) is a series of photographs paying homage to their love. She also gave up filmmaking to concentrate on photography, but two of her early films are on show. Sitting on a veranda, the Austrian sculptor Franz West exposes himself to Warhol-style scrutiny. Trying to hide his embarassment, he adopts various expressions – from heroic, pensive and nonchalent to self-important and seductive; despite his best efforts, his insecurity shines through in a rather endearing way. Similarly exposing herself to view, Kubelka gradually relaxes from self-consciousness into a smiling acceptance of being watched.

Friedl vom Gröller changed her name when she married film director Peter Kubelka. Voyage, 1974 (pictured left: Toulon 26.4.74 ) is a series of photographs paying homage to their love. She also gave up filmmaking to concentrate on photography, but two of her early films are on show. Sitting on a veranda, the Austrian sculptor Franz West exposes himself to Warhol-style scrutiny. Trying to hide his embarassment, he adopts various expressions – from heroic, pensive and nonchalent to self-important and seductive; despite his best efforts, his insecurity shines through in a rather endearing way. Similarly exposing herself to view, Kubelka gradually relaxes from self-consciousness into a smiling acceptance of being watched.

She describes her films to me as photographs extended in time and, looking through the monograph dedicated to her, what strikes me is her singularity of vision; the same sensibility is evident in fashion shots, commissioned portraits and her own work. Kubelka is fascinated by the relationship between photographer, sitter and viewer, which she describes as a “subtle fight for identity”. While the photographer tries to seduce the sitter into revealing something normally kept hidden, a conflict rages in the model between wanting to demonstrate a degree of self knowledge and hoping to look their best. If the session is an assignment, the client’s wishes also have to be taken into account and finally, in this complex interplay, the viewer projects their own ideas onto the image.

A case in point is a group of eight unsmiling self-portraits taken over a period of 24 years. “Its a diary”, she explains; “a line of melancholy. I was interested in the relationship between the inner and outer person; the state of mind recurs but the skin gets older.” I perceive her to be getting sadder and more resigned as time passes, but Kubelka insists she feels happier and is achieving greater clarity. My analysis, I realise, is based on a stereotype, and the artist agrees. “The biggest burden of aging”, she says, “is the view society has of you; getting older is shameful. If you are young and suicidal, you still look pretty; but if you are old, you are shameful even if you are not suicidal.”

A case in point is a group of eight unsmiling self-portraits taken over a period of 24 years. “Its a diary”, she explains; “a line of melancholy. I was interested in the relationship between the inner and outer person; the state of mind recurs but the skin gets older.” I perceive her to be getting sadder and more resigned as time passes, but Kubelka insists she feels happier and is achieving greater clarity. My analysis, I realise, is based on a stereotype, and the artist agrees. “The biggest burden of aging”, she says, “is the view society has of you; getting older is shameful. If you are young and suicidal, you still look pretty; but if you are old, you are shameful even if you are not suicidal.”

Since divorcing her husband, Kubelka has begun making films again under her maiden name. In My Precious Skin, 2013, we see a woman lathering her face and hands with expensive creams in an attempt to hide the tell-tale signs of ageing. Guilty Until Proven Innocent, 2013, shows a huddle of middle-aged women sequestered behind chicken wire. Their crime? No longer being young.

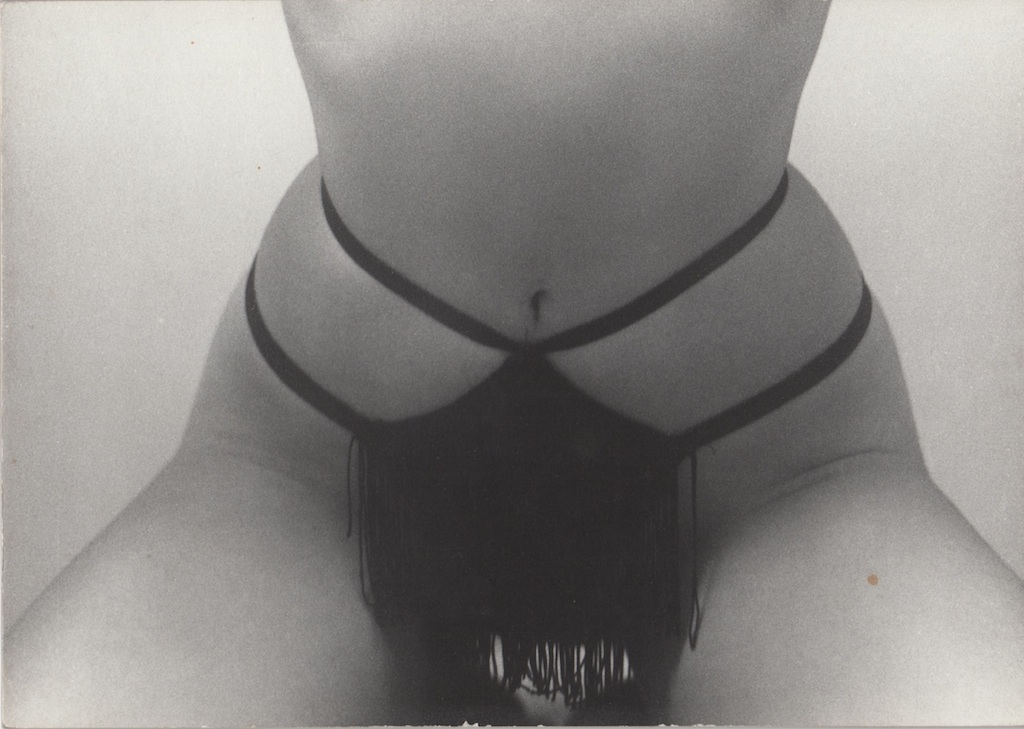

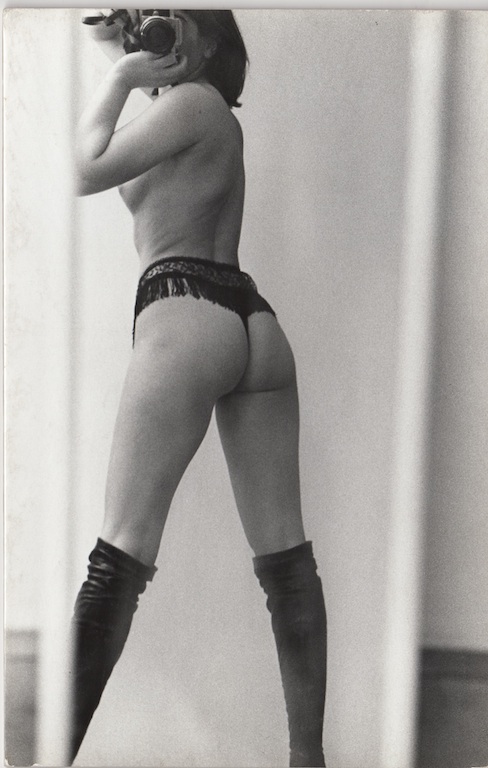

As a young woman, Kubelka explored her sexuality in a series of photographs taken in Paris hotels. Renting a room by the hour, she stripped to sexy underwear and photographed herself in the mirror, as if posing for a client. The shots are highly ambiguous since, in effect, we are the clients and her solitary striptease is more about our voyeurism than her hedonism. Her pleasure is derived from satisfying our peeping Tom desires which, of course, is how female sexuality has traditionally been portrayed. For Pin-ups, 1971, she photographed herself in a slimming mirror so that her image would conform more closely to a desired shape – again viewing herself through the eyes of others.

As a young woman, Kubelka explored her sexuality in a series of photographs taken in Paris hotels. Renting a room by the hour, she stripped to sexy underwear and photographed herself in the mirror, as if posing for a client. The shots are highly ambiguous since, in effect, we are the clients and her solitary striptease is more about our voyeurism than her hedonism. Her pleasure is derived from satisfying our peeping Tom desires which, of course, is how female sexuality has traditionally been portrayed. For Pin-ups, 1971, she photographed herself in a slimming mirror so that her image would conform more closely to a desired shape – again viewing herself through the eyes of others.

In one way or another, Kubelka’s work is an exploration of identity – how we perceive ourselves in relation to how the world sees us – so it comes as little surprise that, in 2000, she began working as a psychoanalyst, a career she pursued for seven years. I was lucky enough to gain first hand insight into her interesting ideas; otherwise I would not have gleaned so much, since the show is too modest an introduction to enable one to understand a lifetime’s work. More please!

- Valie Export and Friedl Kubelka: Viennese Season: Feminism at Richard Saltoun until 23 May

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment