theartsdesk at the Marrakech Biennale: "Where Are We Now?" | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Marrakech Biennale: "Where Are We Now?"

theartsdesk at the Marrakech Biennale: "Where Are We Now?"

The bienniale has left its mark on the city, but the artworks still have to compete with the colourful backdrop

Whether fingerprint or labyrinth, the swirly logo for Marrakech Biennale 5 feels apt. The festival has left its mark upon the city. It questions Moroccan notions of identity. And, going by the tagline, “Where are we now?” it reflects the ease with which you can get lost in this rich and bewildering land.

But the artists in this 10-year-old event, know their way round North Africa. Almost a quarter of the 43 participants are from Morocco. Many more have strong links with the region. And the majority of works are site-specific, that is, fully orientated to the five main venues.

Curator Hicham Khalidi is himself Moroccan, via the Netherlands, and so well placed for an overview of this North African country which has one foot in the West, with its tourism industry, and one in the Islamic world. At intervals, a hectic call to prayer rings out across the Medina. If art has become a religion in the West, it cannot compete with Islam in the narrow streets and busy squares of Marrakech. Art has trouble enough competing with snake-charmers, tame monkeys, Gnawa musicians and all the rest of the local sights which are, as you surely already know, colourful.

But at least within the realm of contemporary art East and West meet quite well

Of course, the beauty of dancing cobras is that few will need a guide to grasp what’s going on. The same cannot be said for many installations of contemporary art. And to a point, MB5 is let down by its interpretation. Wall plaques, in English, French and Arabic, don’t always fully unpack the works; the programme limits itself to noting who commissioned or paid for each work. On opening day, admission was free, and local people crowded the venues to make of it what they could.

But once you get the lowdown on it, there is plenty of compelling and relevant art. Indian artist Asim Waqif has knocked up a playful and tuneful “pavilion” from wooden junk found outside a royal palace. Turkish artist Burak Arikan uses an algorithm to compile a montage from the official commercials of tourist offices throughout the world. It captures the monotony along with the ecstasy of travel. (Pictured above right: Hicham Benohoud, Bienvenue à Marrakech, 2014)

But once you get the lowdown on it, there is plenty of compelling and relevant art. Indian artist Asim Waqif has knocked up a playful and tuneful “pavilion” from wooden junk found outside a royal palace. Turkish artist Burak Arikan uses an algorithm to compile a montage from the official commercials of tourist offices throughout the world. It captures the monotony along with the ecstasy of travel. (Pictured above right: Hicham Benohoud, Bienvenue à Marrakech, 2014)

One of the festival’s undoubted hits so far is by the cosmopolitan Éric Van Hove. Born and raised in Africa, the Belgian artist worked with local craftspeople to make components for a replica F1 engine (main picture). It is a neat way to explore the driving force behind Morocco's economy and provide a local riposte to that race-to-market which characterises western style capitalism.

Van Hove’s work also ignites a debate around tourism and the alleged diminishing quality of goods on sale in the nearby streets. Marrakech has claims to be the most visited city in Africa and this global arts festival aims to boost tourism even further. As a holiday destination it is hard to resist, and local crafts do put food on the table. But if high-end, artistic products find it hard to compete, there may one day be a cultural cost.

For me the most remarkable work on show takes the Biennale out onto the streets and mixes it with the stallholders and the orange juice vendors. This is Saâdane Afif’s performative work, Souvenir (La leçon de géométrie), in which he lectures on geometry in the pulsating Jamaa El Fna city square. On the evening of my visit, his topic was the circle and a good many locals were rapt. As his flipchart filled with symbols and diagrams, one recalled the importance of geometry to Arabic science and the Islamic arts. This was culture in the raw.

In daylight hours, Afif’s flipchart resides in the adjacent Bank Al Maghrib. This is the most diverse and exciting of the Biennale’s venues. The grandiose setting hosts 23 artists and offers breathtaking views from the terrace. It also features a vault-lined basement, where Tala Madani’s darkly comic animations find themselves at home. The historic and well-appointed warren of rooms here is conducive to encounters with art.

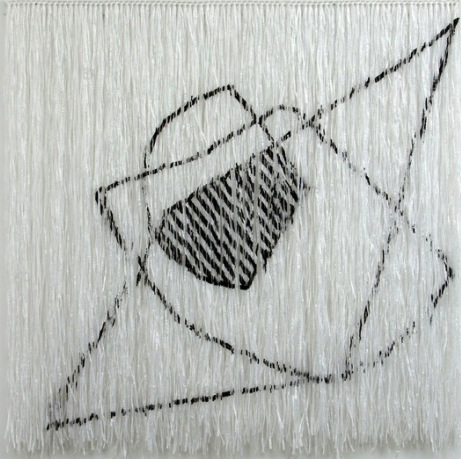

Nearby Dar Si Said has charms of a different order. This 19th-century mansion is home to the Museum of Moroccan Arts. Artefacts by the Berber civilisation, which is reputed to be 9,000 years old, now sit cheek-by-jowl with art from 2014. Adriana Lara infiltrates the collection with carpets, sitting alongside the permanent displays, incognito (pictured left: Interesting Theory #11-b, 2012). She has also put up several artworks for sale in the nearby souk. Lucky punters could find themselves haggling for exclusive pieces of art.

Nearby Dar Si Said has charms of a different order. This 19th-century mansion is home to the Museum of Moroccan Arts. Artefacts by the Berber civilisation, which is reputed to be 9,000 years old, now sit cheek-by-jowl with art from 2014. Adriana Lara infiltrates the collection with carpets, sitting alongside the permanent displays, incognito (pictured left: Interesting Theory #11-b, 2012). She has also put up several artworks for sale in the nearby souk. Lucky punters could find themselves haggling for exclusive pieces of art.

In a festival which communicates in at least three languages, music plays a key role. One of the most arresting pieces at Dar Si Said features a white cube in which four musicians are trapped. We see their arms and we see and hear their instruments. But there is no way of getting round the pristine barrier. It could well be that artist Gabriel Lester is commenting on the invisibility of the ancient culture, to some extent hidden and suffering some neglect in this grand but fading villa.

As we heard several times in our visit, Morocco has an oral tradition rather than a museum culture. A look around the jumbled displays in Dar Si Said bears this out. In her book on the country, Edith Wharton even went so far as to identify this “central riddle” in North African civilization: “The patient and exquisite workmanship and the immediate neglect and degradation of the thing once made.” It makes little sense to Western thinking, but never the twain, etc.

But at least within the realm of contemporary art East and West meet quite well. Another key venue, L’Blassa, is a 1932 art deco building in the French district. The café into which artist Hassan Hajjaj has turned the foyer would not be out of place in East London. And follow the narrow stairs to the first floor and you will find a four-part installation using recycled garbage. Z’Bel Manifesto, all from Marrakech, are the art collective behind this well-executed work. Its “message” is a universal response to the question, “Where are we now?”

This brings us to epic venue Palais El Badii, where the art could so easily have got lost. It is a 16th-century palace, stripped of all ornamentation. And in one way or another, the work here seems camouflaged: a fabric shelter in a courtyard could be permanent; the sounds here could come from the noisy storks on the battlements. The latter is in fact a bewitching sound installation by Turkish artist Cevdet Erek. He hasn’t tried to compete with this exotic city. That would be a losing game.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment