10 Questions for Director Tom Morris | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Director Tom Morris

10 Questions for Director Tom Morris

The co-director of 'War Horse' has created 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' with Handspring's puppets. Here's how

Two lanky, totemic marionettes with stern carved faces – one male, one female – coast haltingly around a rehearsal room in Bristol. They are being operated from inside metal framing by actors who coax tentative movement into arms and necks. “Use stillness as one of the things in your arsenal,” suggests a South African voice from the wings. “How are you doing for fatigue?” enquires a patrician English voice.

The South African accent belongs to Adrian Kohler of the Handspring Puppet Company. The English director is Tom Morris. The last time they worked together they came up with War Horse. For their next trick they have conjured up a version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream featuring these two splendidly imposing figures. Last year it opened at Bristol Old Vic, where Morris is artistic director after spells at the Battersea Arts Centre and the National Theatre. It arrives at the Barbican this week.

The concept is built on solid intellectual foundations. This is the quintessential play about make-believe, featuring not only fairies and magic but also a company of am-dramming artisans using crude artifice to put on a royal entertainment (pictured below right, David Ricardo Pearce as Oberon). But from the start Morris has been very much in the business of dampening down expectation. “If people want to see a big emotional story with an animal puppet in the leading role they should go and see War Horse,” he suggests. “And if they want to see a strange experiment by some of the people who were involved in that strange experiment but which will have no resemblance to it, then they should come and see A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” He talks to theartsdesk about dreaming the Dream, and its illustrious stablemate.

JASPER REES: How much of a causal connection is there between this Dream and War Horse?

JASPER REES: How much of a causal connection is there between this Dream and War Horse?

TOM MORRIS: There’s a certainly an overlap. The reason for wanting to work with Adrian Kohler and Handspring Puppets on War Horse was that I’d seen their work at Battersea Arts Centre in 1995 and had thought the puppetry design was completely extraordinary. There was a hyena in their show The Fastest in Africa which basically stole the show by just breathing and yapping and generally appearing to be alive. And that’s what led me to talk to them about War Horse and quite early in the development, in fact when we thought that War Horse might never happen, I was talking to them about other things and they mentioned a production they had done of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in South Africa and they showed me some sketches they had with them and I thought they were really beautiful and perhaps we should do that at some point at the National theatre. And then War Horse took quite a lot of time and we ended up competing that show and I think it was when we were in the middle or remounting the show in New York and I went seriously back to the conversation and said, ”Look, would you like to revisit A Midsummer Night’s Dream?”, and they were indeed interested in that. They had been to visit the extraordinarily beautiful theatre here in Bristol and were intrigued to find out how puppetry would play in it. And so like a lot of theatre-makers who come and see the theatre, Adrian and Basil were intrigued to find out how their craft might respond to this space. And then we began to talk about it seriously and spent a week knocking around some ideas and thought that we had something to go on. That’s how we ended up doing it.

And yet rather than go back to the old production concept you started again. Why?

We were in Bristol talking afresh about the play and I think it became clear that the things that interested us had their own logic, and that really the most exciting thing to do would be to start afresh on a new production rather than revisit the old one. And the things that interested us were what a world might feel like in which people believed in the spirit world. Shakespeare when he wrote the play was clearly referring to a culture in which the presence of fairies and spirits was vivid and credible in some sense, and also what it might be like to apply the theatrical language of puppetry to a play which seemed profoundly to be about the imagination and changes of shape and changes of heart. And we began to get interested in the ways in which the kind of belief that an audience member has to apply when they’re watching crude puppets play out a scene and they have to imagine it into life, what the connection between that imaginative leap of faith might be and the kind of leap of faith you make when you fall in love. And what vulnerabilities come with that leap of faith. So as we dug further into the thematic material of the play and thought more, and Adrian thought and dreamt more about how he might apply a language of puppetry to pursue that, it just became sensible to pursue those fresh trains of thought rather than pick up old ones.

When someone comes to see this, is the aim to make it as if they are having a love potion squeezed into their eyes and they are going to wake up entirely believing that this world exists?

When someone comes to see this, is the aim to make it as if they are having a love potion squeezed into their eyes and they are going to wake up entirely believing that this world exists?

In some sense. If it works then, yes. The puppets in this are far cruder than the ones in War Horse and stranger. If you end up watching a bit of wood being moved about by someone on stage and you end up believing, even if it’s only for the course of two and a half hours, that it’s alive and in love, you have had a magic potion squeezed in your eyes, haven’t you? You are entering into an insane world where as Theseus says in the play, “The lunatic, the lover and the poet are of imagination all compact.” Sometimes in our rehearsal room it seems like that. That Shakespeare is the poet and we are the lunatic and the lover compact.

Continued overleaf: 'There’s one puppet which seems to be incredibly randy'

What kind of an actor do you need? Presumably someone who hasn’t got a problem with their ego? (Saskia Portway as Titania pictured left)

What kind of an actor do you need? Presumably someone who hasn’t got a problem with their ego? (Saskia Portway as Titania pictured left)

You do need someone who can handle the verse and has the technique to do that. But at the same time you need people who are physically adept, musically pretty good and as you say have the kind of attitude to their work which doesn’t mind being asked to do absurd things and is prepared on occasion to play second fiddle to a piece of wood. You do need an instinctive generosity in order to do that. But what we’ve found – and this is one area in which the experience of making War Horse has been very helpful – there are brilliant actors who instinctively understand that and even if they have no direct experience of puppetry can take to it very easily and readily develop the skills that are required. And particularly on a show like this where, not content with designing a fresh set of puppets, Adrian designed a fresh set which even he didn’t know how to work when he designed them. He says when he designs them he has some instincts how they might work but basically you just have to start from scratch with every new puppet. It’s been an unusual phase of the development of this piece to get the cast in a room with the puppets and begin to see the puppets come to life as the cast learn to manipulate them, and through that process discover who the puppets are. It’s not as if we knew what sort of characters some of the puppets would have until we learnt how to operate them. There’s one, for example, which seems to be incredibly randy. It just has a natural sexual appetite of almost overpowering strength. We call it the "fucking" puppet. We had to work out where in fairy world this puppet would fit. Is it Mustardseed? I’m not sure. Is it Cobweb? That process is very unusual I suppose in terms of creating a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

What are puppets doing in Athens?

Athens is for us an imaginary world as to an extent it was for Shakespeare. There is a line in the play where one of the fairies is talking to another of the fairies and they basically say, “I know you’re in the neighbourhood because you’ve come to bless Theseus and Hippolyta’s wedding.” Titania and Oberon have turned up explicitly to bless the wedding. There is then a little bit of banter about whether or not Titania has been having it off with Theseus and Oberon has been having it off with Hippolyta. And then at the end they do bless the marriage, although it’s quite often cut. So we were interested in what sort of blessing this might be and what was it about Athens in the play, not historically, which made it possible for some fairies to turn up at a wedding and bless it. And partly inspired by being in Bristol but partly also by looking at the history of Shakespeare’s England, we looked at cultures which invited the blessing of spirits at various events, from rural traditions in Shakespeare’s England to the people in Bristol who would carve a face on the front of a ship to essentially invite benign spirits to look after the people who were going to sail in it, to communities in Guatemala, where there is a carved figure called Maximon, who is also called Saint Simon, who a particular family in a village look after for a year and agree to keep continually supplied with lit cigarettes and hooch in order that he is in the right state of mind to fix the problems of the people and ask for help for all the surrounding villages. That led us to place some carvings in Athens which we think are carved by Hippolyta which are there to invite the spirits to the wedding. There is a kind of context.

It connects to the play but it tells us that there are people in this world who believe in the creatures who exist in the forest. I think the reason for attempting to do that is that one of the experiences that we felt we’d had watching productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which is a romantic comedy – but then you read in the programme that people in Elizabethan England took the idea of there being spirits in the woods quite seriously and you go, “Well I don’t really believe that.” That idea that there might be some sort of spirit trapped within a piece of wood, that might be animated by the carving of the face of that spirit as imagined on a piece of wood, whether it’s a figure on a ship or the face of a green man on a boss of the roof of a church in Norfolk, connects with the kind of imaginative invitation that a puppet makes to an audience.

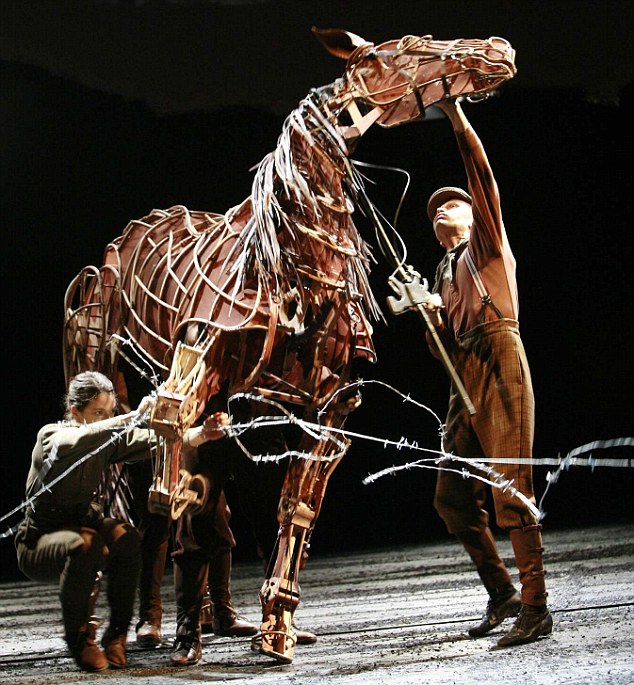

Are audiences now more educated when it comes to buying to the grammar of puppetry? War Horse (pictured right) made a huge difference. The Lion King as well.

Are audiences now more educated when it comes to buying to the grammar of puppetry? War Horse (pictured right) made a huge difference. The Lion King as well.

The Lion King really broke the mould in terms of a puppet being allowed to hold up its head in a theatre and War Horse built further on that. But in Bristol the directors that we end up working with most successfully are people like Emma Rice, Melly Still and Sally Cookson, all of whom sometimes use puppetry in their work but more particularly create a kind of theatre that explicitly appeals to the imagination of the audience rather than trying to fill in every detail in a sort of television-like realistic idiom. And there’s no doubt that that’s the kind of work that inspires me and I therefore try to make. One of the things you can do in a regional theatre which is very hard in London is, through an ongoing conversation with the audience, to develop some ideas about what theatre might be and what direction it might be evolving in.

What was the division of labour between you and Marianne Elliott on War Horse?

When I started work on War Horse I was called associate director but Nick Hytner was asking me to bring less orthodox forms of theatre-making into the practice of the National Theatre, and my job was to come up with ideas and maybe get things going but basically not be trusted to direct them on the big stages. That was about the time that Charlie Spencer [theatre critic of the Daily Telegraph] said I was directing the theatre down a blind alley of physical theatre. Not quite sure what he meant by that. And so I started working on War Horse and the development of it and inviting Handspring Puppets and did a couple of workshops in the NT Studio; and then Marianne came in, Nick suggested we ask Marianne to direct it and having seen her work I thought it was a brilliant idea. She came in and joined in on the next workshop and suggested that we lead together which we did, and at the end she went to Nick Hytner and said, “I think we should do the show with two directors.” It seemed to her there was quite enough going on. When we started out, because I had brought the puppets into the building and my background at BAC as far as it can be generically defined was in relation to devising the theatre process, and Marianne’s background – she had been associate at the Royal Exchange and the Royal Court and had been very influenced by Max Stafford Clark’s school of approaching text, and is still an absolute brilliant investigator of text using now her version of those tools. And when we started out on War Horse she sort of did most of the text and I started out doing staging but quite quickly we were swapping over and in the end there was that much work to do that we didn’t even have time to disagree, we just did what needed to be done. From my point of view that was a priceless experience. Working so closely with her I got to see far closer that you normally do a truly brilliant director working at the height of her powers investigating a text. I have since developed myself a less good version of it.

Has that show changed your life and your work?

Has that show changed your life and your work?

It’s been a huge change for me because you do get a great shot of confidence from having a show which lots of people enjoy, and in particular in that case making a show which challenged lots of the preconceptions and rules of theatre-making. In other words it was a show with a central character that was an animal that didn’t speak, and we were making it in the foremost auditorium for the spoken word in Europe. It was encouraging in relation to the way we did it, which was to build a really exciting creative team and agree between us that we were all going to do something which we couldn’t control which was an experiment and which was beyond our comfort zone. And to do it anyway, which with the protection of the National Theatre we were able to do. It’s also without doubt enabled or helped me to get a job running a theatre outside London. And it’s also encouraged me to create that imagination-led theatre myself and to invite other directors who make that kind of work to Bristol. There are downsides of course but they are very minor, and principally they are the risk that people think whatever the next show I’m going to do might be some sort of War Horse show.

Do you as a theatre-maker feel great empathy with those rude, rough theatre-makers in the play (Miltos Yerolemou as Bottom pictured above)?

Yeah I do. Every time we rehearsed those scenes I realise that Peter Quince is asking the mechanicals to do things which are considerably less absurd than the very things I’m asking the company to do. So yes, I feel a very strong affinity with Peter Quince.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Maiden Voyage, Southwark Playhouse review - new musical runs aground

Pleasant tunes well sung and a good story, but not a good show

Maiden Voyage, Southwark Playhouse review - new musical runs aground

Pleasant tunes well sung and a good story, but not a good show

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Add comment