Obituary: Singer-songwriter JJ Cale | reviews, news & interviews

Obituary: Singer-songwriter JJ Cale

Obituary: Singer-songwriter JJ Cale

An encounter with the quiet man who wrote 'Cocaine', who has died aged 74

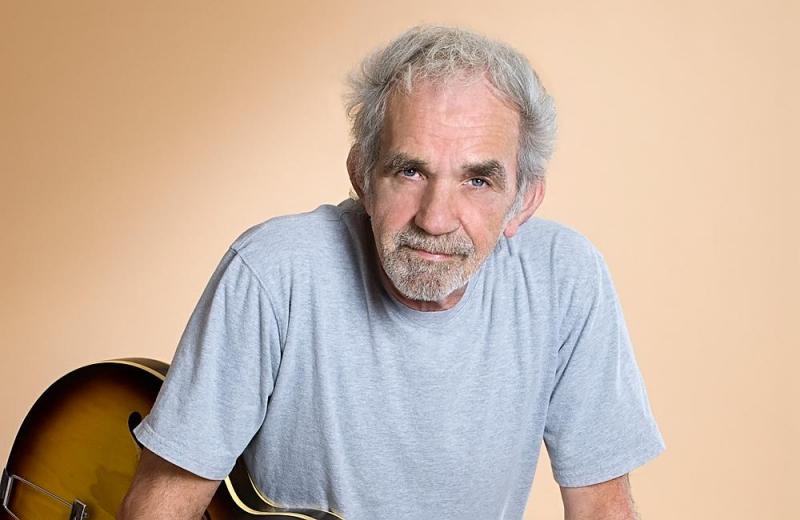

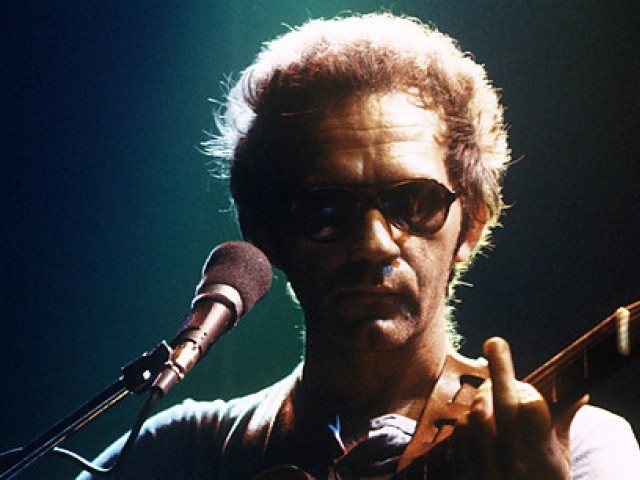

“JJ Cale will be onstage in three minutes.” With the house lights still full on, an old cove with tatty, silvering hair and an open untucked-in puce shirt shuffled about onstage, tinkering with equipment, before picking up a guitar and leaning into a flavoursome sliver of Okie-smoked boogie. Either JJ Cale didn’t give two hoots for the convention of the big entry, or he was enjoying a joke about his anonymity. Probably both.

The musician whose calling card was writing songs for others has died at the age of 74. The reality is that it was a mere three songs which made Cale’s name and fortune: for Eric Clapton there was “Cocaine” and “After Midnight”; for Lynyrd Skyrnyd, “Call Me the Breeze”. Other notable covers included "Cajun Moon" by Randy Crawford, "Clyde" and "Louisiana Women" by Waylon Jennings, "I'd Like to Love You, Baby" by Tom Petty and "Same Old Blues" by Captain Beefheart.

Aficionados and acolytes made it their business to buy the albums by the man who wrote the songs, and in the 1970s there were four of them that wove a subtle kind of modest magic: Naturally, Really, Okie and Troubadour. Ten more followed, as well as a collaboration with Clapton called The Road to Escondido which won a contemporary blues Grammy in 2008. He also appeared on Clapton's album Old Sock this year, performing on his own song "Angel". But the template of what became known as the Tulsa Sound was established early on and Cale never seemed to see the point in setting off on wild tangents. With his one-and-half-note voice, he relied on three chords, occasionally just two, and in the case of his lone hit “Crazy Mama”, pretty much just one.

Cale was an infrequent flier, at least to the UK. He was last here 18 years ago, in 1995, when I interviewed him at the Hammersmith Apollo, which happened to be the same venue as his only other UK date, 18 years previous to that. He didn’t recall much about it himself. Eric Clapton, for whom the 1970s were a decade-long homage to Cale, sat in but, said JJ, “I couldn’t even remember who played bass with me, so you can imagine how I can remember the gigs.”

Cale was an infrequent flier, at least to the UK. He was last here 18 years ago, in 1995, when I interviewed him at the Hammersmith Apollo, which happened to be the same venue as his only other UK date, 18 years previous to that. He didn’t recall much about it himself. Eric Clapton, for whom the 1970s were a decade-long homage to Cale, sat in but, said JJ, “I couldn’t even remember who played bass with me, so you can imagine how I can remember the gigs.”

He was wearing battered beige cords over cowboy boots, and over that puce shirt was a khaki fishing jacket. The costume change for the evening performance would consist of removing the fishing jacket. He was sometimes described as Paul Newman’s shaggy sibling, because somewhere under the crags, the grizzled stubble and bruised cheekbones, deep in the recesses that the stage lights could only cast into pitch-black shadow, were a pair of translucent blue eyes. It was these, doubtless, that slew the women Cale sang of in the doodles that passed for his lyrics.

In Tulsa in the late Fifties, Cale embarked on a shambling career that would turn him into a one-man encyclopaedia of American roots music. In those sideman days Cale picked up rock’n’roll, country, western swing, polka, blues. “You’d take a hundred people in a nightclub,” he told me in an Oklahoma drawl that elided and emphasised words in a kind of jerky poetic rhythm. “And some of them will be old and they’ll want old-style music and some of them’ll be young and want the latest happening thing so you have to play all kinds of music or they’ll punch you out.” Years later, on his debut album Naturally (1972), recorded in Nashville, it all went into the soup.

By then Cale was 32, “beyond the sell-a-lot-of-records age”. The only drummer he could afford was Ace Tone Rhythm Machine. Then came the songs that meant he never really needed to work again, but he toured anyway to get out of the house – he lived in a remote part of southern California where for 10 years he didn’t even have a phone - and because “there’s a few people everywhere want to hear the guy that wrote [them]”.

The songwriting seems to have been an accident. “After Midnight” started out life without lyrics. The words, he suggested, “don’t look good on the page”. “I was working on an album of instrumental stuff back in those days, mid-Sixties, I guess it was, ’65, and I don’t know, we didn’t see it, it didn’t come out, it was out-takes or whatever, and I had that one track. I went back and added words to it. I was down playing Atlanta, Georgia, in nightclubs and people were dancin’ and drunk and I heard some guy holler out, ‘Let it all hang out.’ So I stuck that phrase in the song.”

Cale was essentially a loner. At that Hammersmith Apollo concert he came on alone and was gradually joined by other musicians who in due course gradually left again. By the end he was on his own again. It was as if he was building a sound only to strip it back down again, the way he liked to do with guitars. It's a measure of how seriously he took the whole commercial imperative that he farmed out the titling of his albums to the record company. “The only albums that I have personally named were 5, #8 and Number 10,” he told me. Someone once said that a JJ Cale song sounds like it started long before the beginning you hear on the record, and goes on long after the end. Those great songs of his have been playing for the best part of 40 years now, and it doesn’t look like they’re going to stop just because he has.

- JJ Cale, December 5, 1938 – July 26, 2013

Overleaf: watch Cale perform 'Call Me the Breeze' with Eric Clapton

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Add comment