Reissue CDs Weekly: Scott Walker | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: Scott Walker

Reissue CDs Weekly: Scott Walker

Easy listening and continental European intellectualism combine on the early albums from pop’s wilful auteur

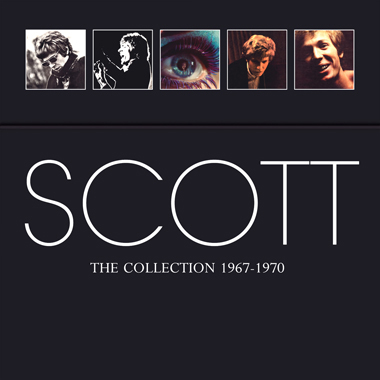

Scott Walker: The Collection 1967-1970

Scott Walker: The Collection 1967-1970

Few pop records possess a beauty taking them into the otherworldly, inexplicable realm where it’s impossible to understand the magic which coalesced in their creation. The Four Tops’ “Seven Rooms of Gloom”, Joy Division’s “Atmosphere”, Billy Fury’s “Halfway to Paradise”, ABBA’s “Dancing Queen”, Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream”, Sigur Rós’ "Hoppípolla”: all channel something other, rapturously embracing the listener.

Another such is Scott Walker’s “Boy Child”, the string-bedded contemplation he wrote which closed side one of his fifth solo album, 1969’s Scott 4. The reissue of the album, and its inclusion in a box set alongside Scott (1967), Scott 2 (1968), Scott 3 (1969) and 'Til the Band Comes In (1970), offers an opportunity to wallow in and reassess these strange albums. His tangential fourth album, Scott Walker Sings Songs From His TV Series, is missing (the inclusion of the bets-hedging 'Til the Band Comes In ends the set on a low) meaning that The Collection 1967-1970 doesn’t compile all his solo material from the period – single and EP-only tracks are also not included.

The box set is released in the wake of Walker’s last album, Bish Bosch. That and its predecessors The Drift and Tilt codified Walker as an artist with little time for niceties such as melody, linear song structure and compositions helpfully grounded in rhythm. His lyrics are allusive and obscure; the 21st-century Walker isn’t courting anyone except his own muse.

The way Walker is perceived depends on when he was first encountered. The helmet-haired transplant from America first made waves in 1965 as one-third of The Walker Brothers, who rose to the top of the charts with the Righteous Brothers knock-off “Make it Easy on Yourself”. Neither brothers nor born Walker, the trio looked brilliant, sounded fantastic and instantly reached the upper rungs of pop’s pecking order.

The way Walker is perceived depends on when he was first encountered. The helmet-haired transplant from America first made waves in 1965 as one-third of The Walker Brothers, who rose to the top of the charts with the Righteous Brothers knock-off “Make it Easy on Yourself”. Neither brothers nor born Walker, the trio looked brilliant, sounded fantastic and instantly reached the upper rungs of pop’s pecking order.

Although John Walker (John Maus) was originally positioned as the lead singer, Scott Walker (Scott Engel) soon supplanted him. Maus's day-to-day voice was no match for Scott’s moody vocalising. The first Walker Brothers album, released in January 1966, had included a cut co-written by Engel, the only contribution from one of the trio. The EP Solo Scott - Solo John, with two tracks from each, was issued in December 1966. A solo Scott was inevitable.

But the solo Scott soon became a square peg, neither fitting the pop or easy listening moulds, and he certainly wasn’t psychedelic or rock. But his music was serious, grown up, and a professed influence on David Bowie. Inevitably, the ex-Walker Brother achieved diminishing returns in terms of sales with Scott 1-4, which is why 'Til the Band Comes In attempted to place him back in the mainstream. After brushes with schlock, it took a while for his more individual path to resurface on parts of the 1978 Walkers' reunion album Nite Flights.

In the aftermath of punk, the introduction to Walker's music came via the 1981 Julian Cope-compiled Fire Escape in the Sky: The Godlike Genius of Scott Walker. Walker’s influence was then heard in Cope’s Liverpool contemporaries Echo & the Bunnymen's lush 1984 album Ocean Rain. Between the two, the newly-deified Walker returned to music with 1983’s Climate of Hunter. The first four albums here pinpoint the emergence of today's Scott Walker: the cult figure recognised in 1981 rather than the pop star of the Sixties or the directionless singer of the early Sevenities.

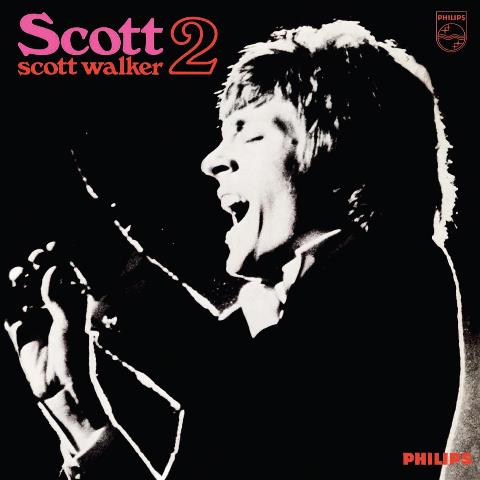

Solo, Scott set his stall with the single “Jackie” (heard on Scott 2). A Jacques Brel song with English lyrics by Mort Shuman, its arrival probably wasn’t that much of surprise to fans back then. The liner notes of the second Walker Brothers’ album Portrait had described Scott as “the existentialist who knows what it means and reads Jean-Paul Sartre… who is inspired by the work of artistes like Jack Jones.” There it was in black and white – the marriage of easy listening and continental European intellectualism.

Solo, Scott set his stall with the single “Jackie” (heard on Scott 2). A Jacques Brel song with English lyrics by Mort Shuman, its arrival probably wasn’t that much of surprise to fans back then. The liner notes of the second Walker Brothers’ album Portrait had described Scott as “the existentialist who knows what it means and reads Jean-Paul Sartre… who is inspired by the work of artistes like Jack Jones.” There it was in black and white – the marriage of easy listening and continental European intellectualism.

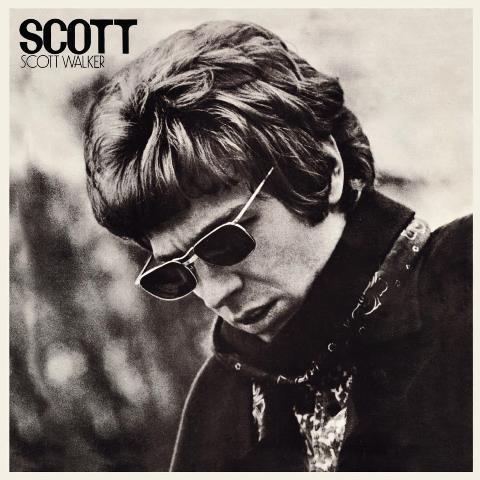

He had been writing songs for the Walker Brothers and continued on Scott with the sonic psycho-geography of “Montague Terrace (in Blue)”. He also covered Tim Hardin’s “The Lady Came From Baltimore”, encasing it in north European glass. His cohorts on this mission were the arrangers and conductors Reg Guest, Peter Knight, Keith Roberts and Wally Stott, whose lush scores were never bombastic, always deft and sensitive.

Scott 2 again brought Hardin and Brel to the table, alongside Scott's own songs. Most amazing is “Plastic Palace People”, where rising and falling strings and waterfall plucking colour a portrait of the disengaged and cynical. This portmanteau piece was his most advanced composition so far, perfecting the filmic style still heard on Bish Bosch.

Scott 4 is the pick. The atmosphere of Bergman filtered through Ennio Morricone, Nino Rota and Sinatra with touches of Gordon Lightfoot, it hardly sold and didn’t chart. The subsequent album, 'Til the Band Comes In, was an inconsistent mix of contemporary covers, songs from musicals, country and less memorable original material co-written with his new manager. The main attraction didn’t even sing on one track, leaving that task to his manager’s other charge Esther Ofarim. It was as though he had given in.

Scott 4 is the pick. The atmosphere of Bergman filtered through Ennio Morricone, Nino Rota and Sinatra with touches of Gordon Lightfoot, it hardly sold and didn’t chart. The subsequent album, 'Til the Band Comes In, was an inconsistent mix of contemporary covers, songs from musicals, country and less memorable original material co-written with his new manager. The main attraction didn’t even sing on one track, leaving that task to his manager’s other charge Esther Ofarim. It was as though he had given in.

This package includes a book with reprints of fascinating contemporary interviews with Scott, as well as a new essay and insightful album-by-album commentary by The Wire’s Rob Young. "Scott considers his work anti-LSD and anti-flower power," said the NME in 1967.

Each album has been out on CD before and it’s hard to tell what new mastering these fresh versions have had. The credit is “Mastered at: Abbey Road Studios”. Nothing else, no clue. Master tapes would seem to be the source, not previous digitisations, as the sound here has a dynamism and fat mid-range lacking on previous CDs, including the 1990 comp Boy Child.

The Collection 1967-1970 is also issued as a vinyl box, which was not made available for review. In the last 10 years, there have been at least two editions of each album on vinyl, most (especially the American issues) with a brittle sound counter to the warmth of the original albums (and, indeed, these new CDs). Hopefully, the new vinyl reissues are fully-analogue products and will right that wrong.

Scott Walker was the subject of a themed box set in 2003, which also included Walker Brothers' material. It doesn’t undermine this. With the ease of availability of the five albums individually, the essentialness of this set rests on the attention paid to its production. If you have the original albums, don’t bother. If you have any of the other CD reissues, sell them and get The Collection 1967-1970 instead. Comments welcome from anyone who gets the new vinyl versions.

Watch Scott Walker perform “Jackie”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Tom Grennan - Everywhere I Went Led Me To Where I Didn't Want To Be

British pop star's fourth exhibits ultra-pop oomph with mixed results

Album: Tom Grennan - Everywhere I Went Led Me To Where I Didn't Want To Be

British pop star's fourth exhibits ultra-pop oomph with mixed results

Album: Emma Smith - Bitter Orange

The award-winning jazz singer brings new life to some classic standards

Album: Emma Smith - Bitter Orange

The award-winning jazz singer brings new life to some classic standards

Add comment