Saloua Raouda Choucair, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Saloua Raouda Choucair, Tate Modern

Saloua Raouda Choucair, Tate Modern

A long overdue retrospective of this little-known Lebanese artist

Saloua Raouda Choucair began her career as a painter, initially studying under Lebanon’s two leading landscape artists, Mustafa Farroukh and Omar Onsi. In the late 1940s, she trained in the studio of Fernande Léger while studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Her exposure to art in her native Beirut would have given no hint of the vibrant modernism she would embrace, albeit several decades after Europe had been all aflush with the new.

Her modernist mask of pallid grey tones is enlivened with strips of yellow

We begin with an elegant, autumnally Fauvist self-portrait of 1943. Arresting almond eyes, their blackness emphasised with thick layers of kohl and dark angular eyesbrows, slide their gaze past us with cool insouciance. Her modernist mask of pallid grey tones is enlivened with strips of yellow that suggest her olive complexion. Colours don’t, in fact, veer too wildly from the descriptive.

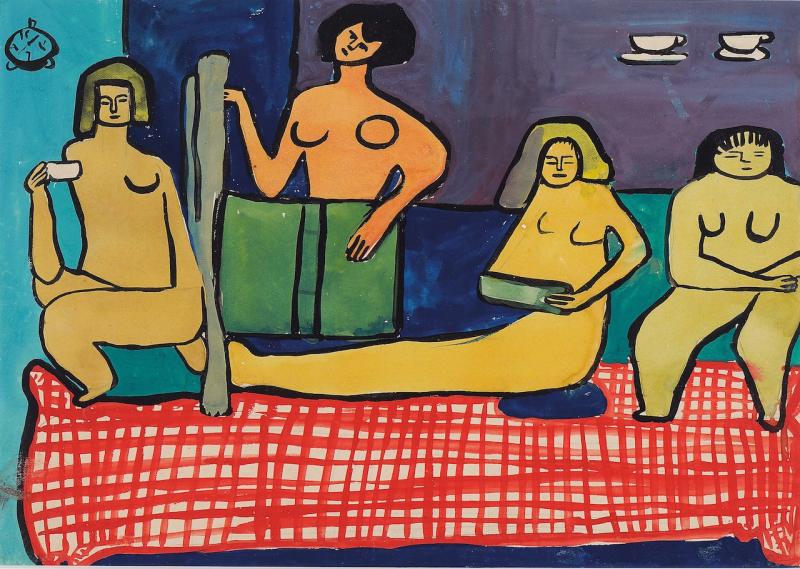

Then we quickly skip to the late Forties and early Fifties and Léger’s influence, and that of Matisse, is evident. Her subjects are the monumental odalisque, painted on a small scale, on paper. She adopts a bolder palette and paints flat areas of colour and there’s the occasional art deco decorativeness, such as we see in the delightful Nude with Iris, 1948-9. In a series of paintings of the same period, Les Peintres Célèbres (main picture: Les Peintres Célèbres I), she’s taken Léger’s huge 1921 painting Three Women, with its three moon-faced machine-automaton nudes, and turned them into cruder cartoons. They still have their cups of tea and their books, but it’s a long way from Léger’s smooth, clean precision in which all life begins as a cube, a cone or a cylinder.

Her figurative works give way to rhythmic abstract paintings featuring repeated motifs. (Pictured right: Composition in Blue, 1947-51). Shards and arcs of colour float or dance on seas of different colours, like late Bridget Rileys. But soon she eschews both colour and flat surface and turns to sculpture, with which she will make her most definitive statement as an artist. It is sculpture, carved from wood or stone, shaped from terracotta, or cast in bronze and brass and later constructed from steel, Plexiglass and string, for which Choucair must gain recognition. These are the works – finished pieces, maquettes and models for public projects that never came to fruition – that are the main focus of the exhibition.

Her figurative works give way to rhythmic abstract paintings featuring repeated motifs. (Pictured right: Composition in Blue, 1947-51). Shards and arcs of colour float or dance on seas of different colours, like late Bridget Rileys. But soon she eschews both colour and flat surface and turns to sculpture, with which she will make her most definitive statement as an artist. It is sculpture, carved from wood or stone, shaped from terracotta, or cast in bronze and brass and later constructed from steel, Plexiglass and string, for which Choucair must gain recognition. These are the works – finished pieces, maquettes and models for public projects that never came to fruition – that are the main focus of the exhibition.

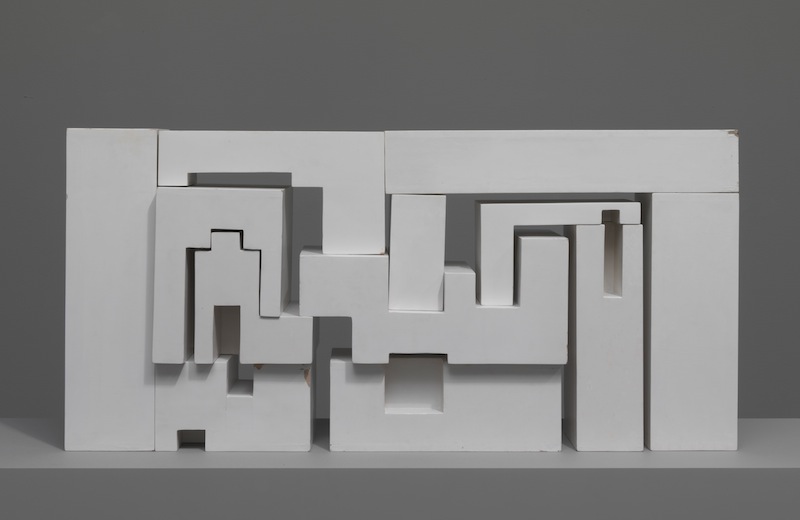

Here the abstract forms of western modernism meet the abstract forms of the Islamic tradition. Interlocking geometries, not perfect nor precise, produce something sensual, suggestive and rather playful. Poem Wall, 1963-5 (pictured left), carved from wood and painted white, is a jigsaw of geometric pieces. Voids are created from the loosely fitting pieces, and the sculpture’s provisional quality – it could all come tumbling down – suggest the modernist’s fascination with chance and the ephemeral, rather than the enduring and the eternal of Islamic art.

Here the abstract forms of western modernism meet the abstract forms of the Islamic tradition. Interlocking geometries, not perfect nor precise, produce something sensual, suggestive and rather playful. Poem Wall, 1963-5 (pictured left), carved from wood and painted white, is a jigsaw of geometric pieces. Voids are created from the loosely fitting pieces, and the sculpture’s provisional quality – it could all come tumbling down – suggest the modernist’s fascination with chance and the ephemeral, rather than the enduring and the eternal of Islamic art.

Duchamp naturally comes to mind when we get to Choucair’s hand-sized brass and aluminium sculptures. Part of an on-going series called Duals, these feature two interlocking pieces, one brass, the other aluminium. They’re a bit phallic and also a bit Yin and Yang. Meanwhile, Sculpture with One Thousand Pieces, 1966-8, suggest stacked crates or a towerblock. Here it’s the painstaking craftsmanship that stands out.

The final room is a revelation, so different from what has preceded it. It’s as if Choucair has lived many different lives as an artist. These buoyant string, steel and Plexiglass works from the Seventies and Eighties, in which pieces of glass are held in perpetual tension, shimmer and glow in the dimmed light.

Tate has organised this small but densely packed retrospective on its top floor and this is a good move. How often have their vast fourth-floor displays of even major artists simply felt too padded out? The size of this exhibition feels just right.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment