Interview: Stephan Micus, the world's largest one-man band | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Stephan Micus, the world's largest one-man band

Interview: Stephan Micus, the world's largest one-man band

Hailing a 20th album album and rare UK appearance for the Bavarian multi-instrumentalist and unsung genius

"Multi-instrumentalist" is a catch-all phrase that usually means somebody who plays flute, clarinet, sax and perhaps a bit of guitar. When it comes to Stephan Micus, he’s a multi-instrumentalist of an altogether different calibre. He plays hundreds of instruments – he doesn’t know how many – which he’s collected and commissioned from all over the world.

Micus, who has a rare London concert this month, has just released his 20th album on ECM, which puts him up there with Keith Jarrett as one of the label’s most prolific artists. But Micus’s art is of a totally different nature. While Jarrett spontaneously plays 66 minutes of improvisatory solo piano, as he did in his best-selling 1975 Cologne Concert, Micus plays his instruments in meticulously planned multi-tracked recording sessions which may take two or three years to put together. I believe Micus is an unrecognised genius making music that has a universal spirituality and is unlike that of anybody else.

The shakuhachi maker said he was never going to make such an instrument again

When someone has recorded so much, where do you start? Actually his new album Panagia is a good place. It is very beautiful, elegantly symmetrical in structure and dedicated to what he describes as “the female energy that is everywhere in the world”. John Tavener has used the phrase “eternal femininity” to describe the power of the Virgin in Orthodox Christianity. Micus’ music, although less overtly religious, can sit, or kneel, alongside Tavener’s Protecting Veil or Arvo Pärt’s refined devotional music.

In Greek, Panagia is one of the names of the Mother of God and the album is a setting of six Byzantine hymns to the Virgin. The music has the fervour and restraint of Byzantine art, but not its formulaic quality. His multi-tracked "ensemble" features mainly string instruments, bowed and plucked, that would never normally play together, from Bavaria, India, Pakistan and Chinese Xinjiang. Instrumental pieces alternate with vocal tracks with up to twenty two voices.

Each of Micus’ albums has its own sound world: The Music of Stones (1986) really does feature lots of resonating stones; Desert Poems (2000) has a warm, earthy flavour with Japanese shakuhachi flute over African strings, percussion and thumb piano; Towards the Wind (2001) has a sensation of flying with Armenian duduk and shakuhachi winds over deep plucked strings; and Life (2004) has gongs, chimes and Buddhist philosophy at its heart. There’s an earlier Byzantine-inspired album by Micus called Athos (1994) which featured mainly wind instruments, which is why he’s chosen strings on Panagia. With Micus nothing happens by accident, although the reasoning might be intuitive or philosophical.

Each of Micus’ albums has its own sound world: The Music of Stones (1986) really does feature lots of resonating stones; Desert Poems (2000) has a warm, earthy flavour with Japanese shakuhachi flute over African strings, percussion and thumb piano; Towards the Wind (2001) has a sensation of flying with Armenian duduk and shakuhachi winds over deep plucked strings; and Life (2004) has gongs, chimes and Buddhist philosophy at its heart. There’s an earlier Byzantine-inspired album by Micus called Athos (1994) which featured mainly wind instruments, which is why he’s chosen strings on Panagia. With Micus nothing happens by accident, although the reasoning might be intuitive or philosophical.

Micus has a reputation of being enigmatic and reclusive and, although German born, has lived for most of his creative life in a remote hideaway in Mallorca. He prefers not to say where it is, but it’s in this rugged, dry but beautiful landscape that he’s raised two daughters, built a studio and created his world of extraordinary music.

In his studio, Stephan Micus pulls open a drawer to reveal a dozen bamboo shakuhachi (pictured above). He studied it intensively in Japan and it’s one of the instruments he most frequently uses. He picks one up and starts playing. The sound is a force of nature – a deep, plangent flute sound, but rich in colours and overtones. “This one was made specially for me,” he explains. “It has some extra low notes. The shakuhachi maker cursed me and said he was never going to make such an instrument again because it was so difficult to tune.”

Showing me around his studio (pictured overleaf), Micus pulls open another draw of Armenian duduks and then another of all sorts of reed instruments from Asia and the Middle East. “Some people would kill for the contents of this draw,” Micus says. I haven’t checked out the illicit market in obscure ethnic wind instruments.

Stephan Micus was born in 1953 and grew up in Bavaria. His first instrument was a wind instrument – the recorder, which he learned at school like everybody else. But after hearing flamenco, aged eight or nine, he started learning guitar, then flute and, after hearing Ravi Shankar in the early Seventies, left school and went with $40 to India to learn the sitar. “I ended up in Benares (Varanasi) and my teacher took me in like a son. I studied sitar with him every day for three years. I never invested so much energy in any other instrument.” Despite that, the sitar isn’t an instrument Micus now plays on any of his recordings. “The problem is the sitar is so culturally specific. I found the same thing with the uilleann pipes. There are some instruments where you hear one note and it takes you to a specific world. But my intention is to create a new world with these instruments.”

Stephan Micus was born in 1953 and grew up in Bavaria. His first instrument was a wind instrument – the recorder, which he learned at school like everybody else. But after hearing flamenco, aged eight or nine, he started learning guitar, then flute and, after hearing Ravi Shankar in the early Seventies, left school and went with $40 to India to learn the sitar. “I ended up in Benares (Varanasi) and my teacher took me in like a son. I studied sitar with him every day for three years. I never invested so much energy in any other instrument.” Despite that, the sitar isn’t an instrument Micus now plays on any of his recordings. “The problem is the sitar is so culturally specific. I found the same thing with the uilleann pipes. There are some instruments where you hear one note and it takes you to a specific world. But my intention is to create a new world with these instruments.”

Micus travels about three months a year – collecting instruments and learning to play them, recently in Senegal and with upcoming plans for Sudan and Namibia. “I usually start learning to play them in the traditional way. Then there’s a period of forgetting that and finding my own way to use them. I have a very intimate relationship with these instruments – they are like human beings and each of us has different stories to tell.”

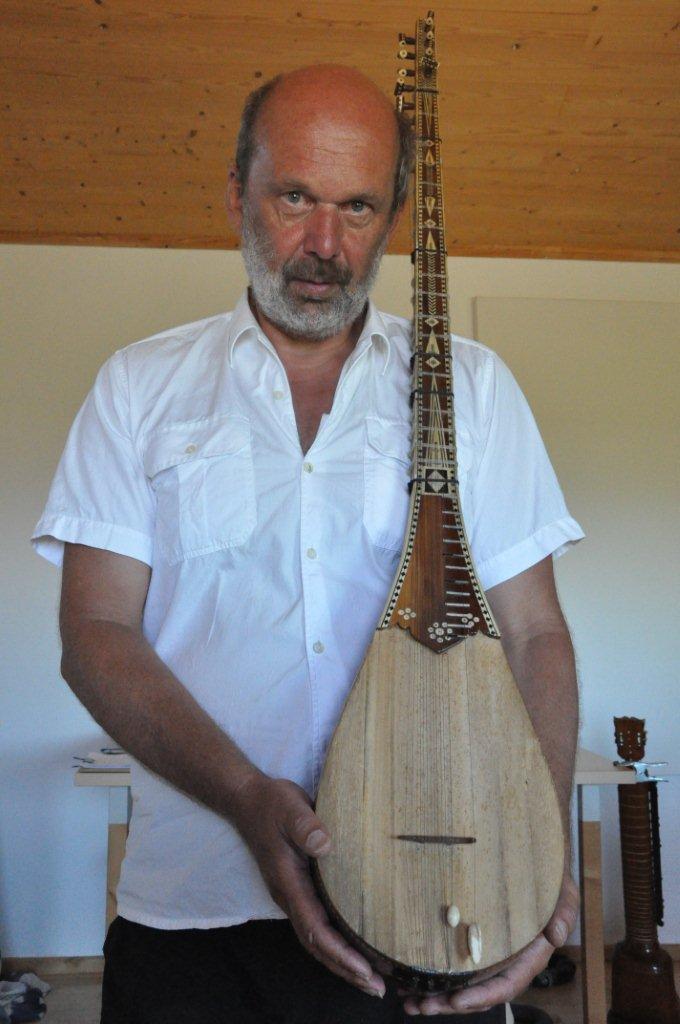

On Panagia he plays the plucked Chitrali sitar from northern Pakistan, the bowed Indian dilruba and the bowed sattar of the Uyghurs (pictured left) in Chinese Xinjiang. “These instruments come from a relatively small area, but are never played together. Now they sound together for the first time thanks to this crazy guy from Bavaria.” This happens on a track called "You Are the Life-Giving Rain": the six dilruba, with a softer tone, and five sattar, with a more scratchy sound, alternate on the melody, while the solo Chitrali sitar plucks a soft accompaniment. It sounds like the music of a long-lost troubadour after which the bowed instruments create a quartet-like polyphonic texture. There’s no other contemporary composer who could have written this – let alone played it.

On Panagia he plays the plucked Chitrali sitar from northern Pakistan, the bowed Indian dilruba and the bowed sattar of the Uyghurs (pictured left) in Chinese Xinjiang. “These instruments come from a relatively small area, but are never played together. Now they sound together for the first time thanks to this crazy guy from Bavaria.” This happens on a track called "You Are the Life-Giving Rain": the six dilruba, with a softer tone, and five sattar, with a more scratchy sound, alternate on the melody, while the solo Chitrali sitar plucks a soft accompaniment. It sounds like the music of a long-lost troubadour after which the bowed instruments create a quartet-like polyphonic texture. There’s no other contemporary composer who could have written this – let alone played it.

I ask about a universal language and Micus says that people all over the world create music for the same reason, which makes it something like a universal language. And then adds: “I’ve made a composition with a Pakistani lute and Indian bowed instrument – and both are an essence of their culture. These two nations are in such antagonism, yet their instruments can play beautiful music together. I wouldn’t make a composition for this reason, but when musical reasons make it happen, I find that pleasing.”

Perhaps the most important instrument on Panagia is Micus’ voice – solo accompanied by zither at the opening and closing, in a choir of 10 accompanied by instruments, and in two pieces as an a cappella choir, of 22 voices in "I Praise You, Lady of Passion". I wonder if there’s any significance to the number 22, thinking perhaps it was the number of rays emanating from the Virgin’s halo in a Byzantine icon. Micus laughs. “I have a 24-track recorder, but I need to keep two tracks to mix down to for the final stereo mix.” A reminder that music is always a mixture of spiritual, artistic and practical matters.

In his concert, Micus will perform the opening and closing pieces from Panagia, which are for solo voice and Bavarian zither, but also bring shakuhachi, Armenian duduk, a Japanese Noh theatre flute and African thumb piano. This will only be his second concert in London in the last 25 years. He can’t reproduce the multi-layered structures of his albums, but he certainly does create a intensity of concentration and a Buddhist-like exhultation in the beauty of sound itself.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment