Classical CDs Weekly: Bruckner, Mahler, Roger Woodward | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Bruckner, Mahler, Roger Woodward

Classical CDs Weekly: Bruckner, Mahler, Roger Woodward

Two epic symphonies and mysterious piano music from Russia

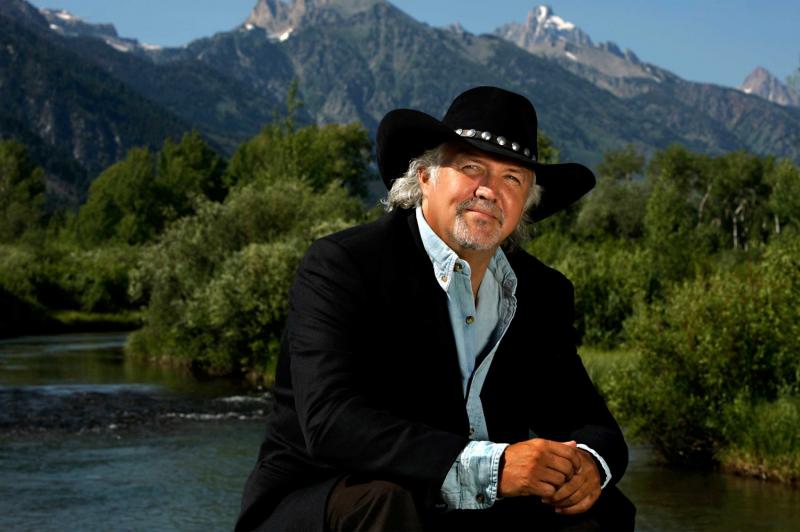

Bruckner: Symphony no 7 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Donald Runnicles (Hyperion)

Bruckner: Symphony no 7 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Donald Runnicles (Hyperion)

Few symphonies start so promisingly. Against tremolando strings, horn and cello sing out a glorious, upwardly mobile melody. The first three movements of Bruckner’s Seventh approach perfection, though I sometimes end up listening to the Adagio and Scherzo in reverse order, having heard Colin Davis perform them that way in a 1980s Prom. The symphony can feel less lop-sided as a result. But it’s hard not to conclude that the Finale is a bit of a damp squib, coming after 50 minutes of pure sublimity. Donald Runnicles’s proven Wagnerian credentials serve this performance handsomely, and he achieves wonders with an underrated BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra who hadn’t played the piece for decades. This is world class playing - the first movement’s coda, radiant and rapturous, is stunning. Brass are forceful but never overwhelming. Strings never sound stretched. The quartet of Wagner tubas are magnificent in the extended Adagio, especially in the mournful, funereal closing minutes.

Bruckner’s naïve, rustic Scherzo bounces and swaggers, and the Trio has oodles of delectable charm – this is music which it’s impossible not to love. After which we reach the Finale. Bruckner’s recycling of earlier material provides some unity, but the endless stops and starts are so, so frustrating to listen to. It’s also insufficiently tuneful, over-stuffed with stodgy sequential writing and too many relentless dotted rhythms. It's as if you’re locked in a cathedral with a drunken organist who’s running out of material. I’ve yet to encounter a performance of this movement which has left me feeling satisfied, but this is my problem and probably isn’t yours. Hyperion’s sound and documentation are flawless.

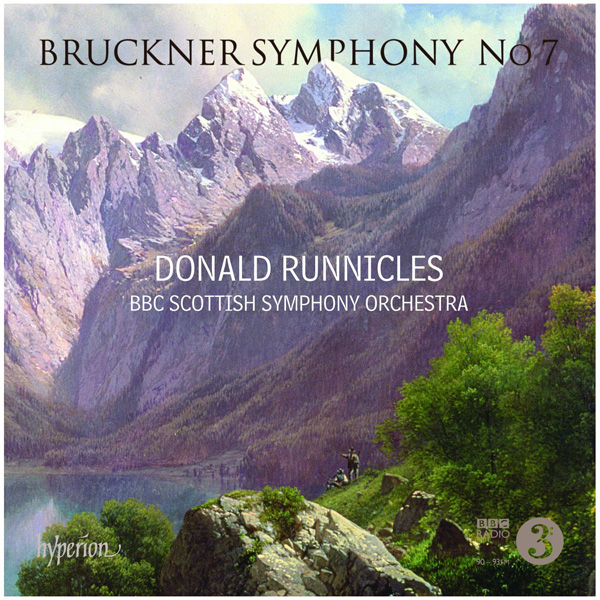

This most precocious of first symphonies can easily lose its power to surprise. Happily, Fabio Luisi’s Vienna Symphony Orchestra performance is pretty special. Unusually for an orchestral own-label release, it’s not a recording of a live performance, taped instead under studio conditions in May 2012. There’s refreshingly little of the routine here – the strangeness, the quirkiness of Mahler’s vision are gently highlighted, the whole aided by gorgeously idiomatic orchestral playing full of refreshingly old-world sonorities. There’s a fruity warmth to the spooky clarinet fanfares heard against the opening string harmonics. Trumpets too are alert and perky, though their offstage calls don’t sound distant enough. Mahler’s lolloping main theme trots out in sublimely laid back fashion, and Luisi’s players manage to project the necessary eerie stillness at the movement’s heart.

As one would expect, the Vienna SO pitch the second movement’s gallumphing dance neatly. Luisi is also impressive in the subsequent "Frère Jacques" parody, though the klezmer band music which follows needs more Bernstein-style vulgarity. Mahler’s extended finale can easily descend into a series of melodramatic episodes. It does hang together well here – the schmaltzy violin theme sings in ripe, Tchaikovskian fashion. And the triumphant close isn’t overblown or bombastic; how refreshing to be able to hear the strings scurrying under the brass peroration. There are flashier, noisier, more flamboyant Mahler 1s around. But this one is excellent, and won’t give you tinnitus.

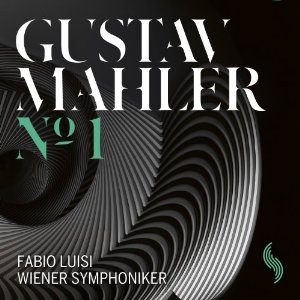

Fabulous – a thoughtful, well-planned recital chock full of the genuinely exotic, the unknown. Roger Woodward studied in Poland in the early 1970s and was able to access a range of material unknown in the West. Most of the manuscripts were found in the archives of Polish state radio, and further information about their neglected composers was provided by Sergei Prokofiev’s widow, Lina. Alexander Scriabin is the only familiar name here, represented by two beguiling miniatures. The earlier Feuillet d’album from 1905 is a dreamy, impressionistic jewel. Five years after, Scriabin composed his first fully atonal piece, identically titled. Atonality doesn’t imply chilliness – this is sensual, heady stuff. Remarkable too are three short pieces by Scriabin’s son Julian, written shortly before his death from drowning at the age of 11. Two precocious preludes by the young Scriabin pupil Boris Pasternak (later to give up music and write Doctor Zhivago) are engaging distillations of the older composer’s earlier, more romantic style.

We enter stranger, more esoteric territory with pieces by Nikolai Roslavets, who developed his own dodecaphonic style, comparable with Schoenberg’s. Stranger still are the Six tableaux psychologiques and Prières written in 1915-16 by Nikolai Obukhov. Aphoristic, unsettling and haunting, the latter’s tolling bell sounds are unmistakenly Russian. We get two powerfully individual Nocturnes from Aleksandr Mosolov, who achieved fame through his industrial tone poem Iron Foundry. Woodward’s comprehensive sleeve notes are a fascinating read, and you can’t imagine a more persuasive guide to this crepuscular repertoire. It's as if you're exploring an alternate musical universe, where Russian and Soviet composers were free to indulge their every whim. Beautifully, sonorously recorded, and nice sleeve art too.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

Album: Saint Etienne - International

British pop institution’s final communiqué is an unalloyed winner

Album: Saint Etienne - International

British pop institution’s final communiqué is an unalloyed winner

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

Album: Brad Mehldau - Ride into the Sun

A sincere tribute to Elliott Smith

Album: Brad Mehldau - Ride into the Sun

A sincere tribute to Elliott Smith

Music Reissues Weekly: The Outer Limits - Just One More Chance

Exhaustive anthology unearths the full story of the Sixties mod-pop band from Leeds

Music Reissues Weekly: The Outer Limits - Just One More Chance

Exhaustive anthology unearths the full story of the Sixties mod-pop band from Leeds

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Add comment