Art of Change: New Directions from China, Hayward Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Art of Change: New Directions from China, Hayward Gallery

Art of Change: New Directions from China, Hayward Gallery

From perpetual free fall to freezing time, Chinese artists respond to rapid change

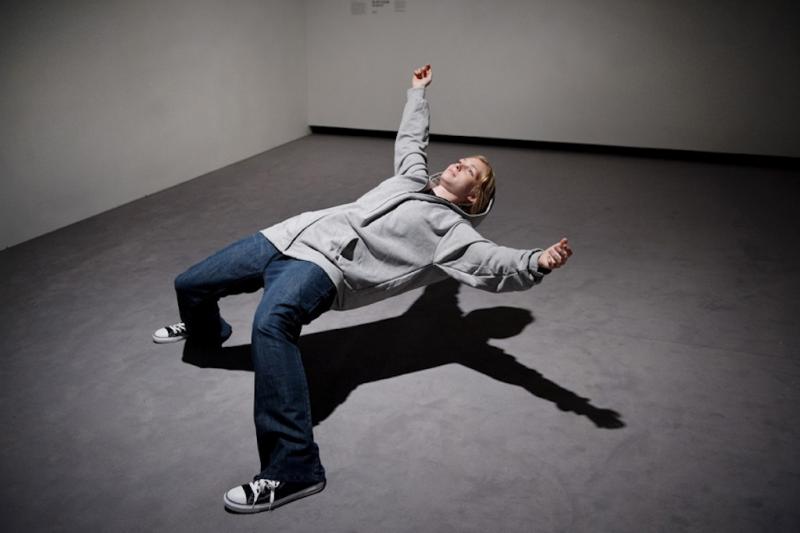

At the Hayward Gallery a young woman falls over backwards; her flight is magically arrested at a gravity-defying point of imbalance. Since she is blinking, one can safely assume that she is alive, present, and human rather than a waxwork or an illusion. How, though, does she sustain such an impossible position?

The perfect embodiment of ongoing instability, this glorious piece by Shangai-based artist Xu Zhen reminds me of that famous Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times!” Currently in the throes of rapid change, China also seems hell bent on erasing its past, with apparent disregard for the effects of modernisation and collective amnesia on its population – the likely fallout from living in extravagantly “interesting times”.

Perhaps that’s why the exhibition Art of Change: New Directions from China feels so disorientating. There are so few points of reference and, although Xu Zhen’s “In Just a Blink of an Eye” is self-explanatory, other works need explication. A lack of information frustrates one’s desire to make sense of some of the key exhibits.

Take, for instance, the work of Beijing based duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. Shown on video, ‘Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other”, a performance involving pairs of fighting dogs, remains as disturbingly confrontational as when it was first staged in 2003. Desperate to draw blood, the dogs run full tilt towards opponents who remain frustratingly out of range since all are harnessed to treadmills, which oblige them to keep running while getting nowhere.

Take, for instance, the work of Beijing based duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. Shown on video, ‘Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other”, a performance involving pairs of fighting dogs, remains as disturbingly confrontational as when it was first staged in 2003. Desperate to draw blood, the dogs run full tilt towards opponents who remain frustratingly out of range since all are harnessed to treadmills, which oblige them to keep running while getting nowhere.

The cruel futility of the rat race could not be more clearly portrayed; but while “Dogs...” needs no explanation, the meaning of “Civilisation Pillar” (pictured above, with “I Didn’t Notice What I am Doing”) is far from evident. This four metre high column resembles a triumphal Roman monument, but in place of marble, there is human fat extracted during cosmetic liposuction. The pillar is an ironic celebration of excess, but its macabre humour is apparent only if you know the grisly facts.

Other items in the room seem part of “I Didn’t Notice What I am Doing”, an installation exploring the supposed relationship between a rhinoceros and a triceratops. The fake skulls, dead bugs and video of a heaving pool of carp seem vaguely to belong in this quasi-scientific investigation, but the wall of car tyres and torpedo-shaped object slathered in red paint and impaled on branches require explanation.

If you want to engage with the work properly, you need help – and it is not forthcoming. As though anticipating difficulties, the curators have supplied a detailed history of recent developments in Chinese art; but to explore the digital archive you have to dedicate time to an experience wholly at odds with the ethos of the work, especially its immediacy. The catalogue is similarly frustrating; earlier work by the nine artists is reproduced in images too small to be legible alongside texts too generalised to be informative.

If you want to engage with the work properly, you need help – and it is not forthcoming. As though anticipating difficulties, the curators have supplied a detailed history of recent developments in Chinese art; but to explore the digital archive you have to dedicate time to an experience wholly at odds with the ethos of the work, especially its immediacy. The catalogue is similarly frustrating; earlier work by the nine artists is reproduced in images too small to be legible alongside texts too generalised to be informative.

Lack of immediacy is also a problem with some displays. In 2008, Xu Zhen recreated – as a diorama – Kevin Carter’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a vulture watching a Sudanese girl die of starvation. Visitors to Zhen’s exhibition were invited to recreate the (in)famous photograph by taking snaps of a Sudanese girl posing beside a mechanical vulture in the mock up of a rural compound. They were offered a clear moral choice – to conspire in the exploitation (like vultures) or refuse to be a party to it. (China’s economic relationship to African countries must surely be a reference point). At the Hayward, though, the provocative installation appears only on video, which lets us off the hook and seriously dilutes the work.

The feeling that vital things are happening elsewhere is compounded by the closed room dominating the space. Gales of laughter emanate from the hidden space, while toys are gleefully tossed in the air. Excluded from the party, Yingmei Duan (pictured above right) sings a plaintive song in a grove of deda branches while pyjama clad sleepwalkers (and viewers) wander round the periphery as though searching for somewhere where they feel less marginalised. Occasionally, one of the lost souls latches on to a visitor and stalks them around the exhibition like a secret service agent, or a bad conscience.

China may be rushing headlong into the future, but for Liang Shaoji who, at 67, is the oldest artist in the exhibition, time seems to stand still. Everything in his space is swathed in silken threads, like Miss Havisham's wedding breakfast. While Chinese shoppers reject traditional silk for modern synthetics, Shaoji breeds silk worms and encourages them to spin their cocoons across casement windows, over large stones, round heavy duty chains and over tiny wire beds (pictured left). Living and working on Tiantai Mountain, the cradle of Tiantai Buddhism, Shaoji focuses on work he describes as “a sculpture of time, life and nature: a recording of the fourth dimension” – as though he were trying to slow the pace of change by reminding us of a more natural cycle.

China may be rushing headlong into the future, but for Liang Shaoji who, at 67, is the oldest artist in the exhibition, time seems to stand still. Everything in his space is swathed in silken threads, like Miss Havisham's wedding breakfast. While Chinese shoppers reject traditional silk for modern synthetics, Shaoji breeds silk worms and encourages them to spin their cocoons across casement windows, over large stones, round heavy duty chains and over tiny wire beds (pictured left). Living and working on Tiantai Mountain, the cradle of Tiantai Buddhism, Shaoji focuses on work he describes as “a sculpture of time, life and nature: a recording of the fourth dimension” – as though he were trying to slow the pace of change by reminding us of a more natural cycle.

Time is also an issue in the work of Chen Zhen. After being diagnosed in 1980, at the age of 25, with a blood disease and given five years to live, Zhen left Shanghai for France where he began making installations. Described by him as “a sort of monochrome tomb”, “Purification Room” (pictured below) is like a 3D sepia photograph; everything in the space is covered with brown mud that cracks as it dries. “Rather than digging in the sand for objects as archaeologists do,” Zhen has explained, “my work consists of showing people present-day objects that will be found in the future.” And the items – from a shopping trolley and scooter to a bike, bath, sofa, skis, books and clothing – are like a catalogue of typical late 20th-century domestic items. Zhen died in 2000 and, installed by his widow, the work is, in more senses than one, a memorial frozen in time.

Art of Change proposes various responses to the accelerating pace of life in contemporary China – from attempting to freeze time, enduring a perpetual state of free fall or sleep walking into the future. The exhibition does not make for comfortable viewing but it provides a fascinating glimpse of how confusing it must be to live in extremely “interesting times”.

Art of Change proposes various responses to the accelerating pace of life in contemporary China – from attempting to freeze time, enduring a perpetual state of free fall or sleep walking into the future. The exhibition does not make for comfortable viewing but it provides a fascinating glimpse of how confusing it must be to live in extremely “interesting times”.

- Art of Change: New Directions from China at the Hayward Gallery until 9 December

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment