Cecil Beaton: Theatre of War, Imperial War Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Cecil Beaton: Theatre of War, Imperial War Museum

Cecil Beaton: Theatre of War, Imperial War Museum

A revelatory new exhibition transforms the elegant society photographer into a gritty war reporter

The wide eyed little girl is sitting bolt upright in her hospital bed, clutching her large soft toy, her head encased in a voluminous bandage. Eileen Dunne, aged three, was injured by shrapnel during the London bombing in 1940, and Cecil Beaton’s Ministry of Information photograph of the bewildered child travelled the world, graced the cover of Life magazine and silently pleaded the British cause.

Seven tow-headed school children solemnly clustered round a table, not a smile to be seen, are evacuees from London, come to rest in a Somerset village school. Brutal heft distinguishes both the people and the shipyards of Tyneside in 1943: surreal compositions of cranes, huge chains, the carcasses of half built ships complemented by determined - and good looking - workers dwarfed by their surroundings and who would not have been out of place in Soviet propaganda.

The Navy is populated by handsome ratings, the Royal Air Force by pilots straight out of Terence Rattigan or Noël Coward, leather-jacketed, ready to fly. The compositions are strikingly memorable, anchored by a sure sense of elegant composition, and curiously like stills from films. Cecil Beaton CBE (1904-1980) had an eye for what would convey, without words, the image of Britain under siege. Unflinching. Getting on with it. There is not a dead body to be seen, although plenty of ruins and ghostly remnants of grand City churches (pictured right, Mary-le-Bow Church from Bomb Debris, 1942).

The Navy is populated by handsome ratings, the Royal Air Force by pilots straight out of Terence Rattigan or Noël Coward, leather-jacketed, ready to fly. The compositions are strikingly memorable, anchored by a sure sense of elegant composition, and curiously like stills from films. Cecil Beaton CBE (1904-1980) had an eye for what would convey, without words, the image of Britain under siege. Unflinching. Getting on with it. There is not a dead body to be seen, although plenty of ruins and ghostly remnants of grand City churches (pictured right, Mary-le-Bow Church from Bomb Debris, 1942).

He was an unlikely war photographer. Beaton is perhaps best known for his elegant, misty eyed portraits of the royals, from the Queen Mother to Princess Anne, with particular attention to the former and her daughter Elizabeth – in 1943 his photograph of Princess Elizabeth in uniform graced the cover of Life - and his images of stars, from Greta Garbo to Margot Fonteyn and the lady leaders of high society. He was a celebrity society photographer par excellence, his work both in vogue and in Vogue, where he was under contract from 1927. Beyond that he had a successful career as a designer for theatre, film and opera: during the war he designed the classic film of Shaw’s Major Barbara, and after the war reached the world stage with, notably, My Fair Lady for stage and film, forming a genuine rapprochement with Audrey Hepburn, Gigi (Leslie Caron) and Puccini’s Turandot for the Metropolitan and Covent Garden.

Beaton had an apprenticeship in photography with the social photographer Paul Tanqueray although he was never to develop and print his own work. Beyond that he wrote extensively with several waspish and entertaining diaries published sequentially, as well as scores of other books, some in collaboration with others, including a pioneering history of photography, The Magic Image, with Gail Buckland. In 1940-1941 contributed over 50 photographs to a text by James Pope-Hennessy to one of the first books on the blitz and beyond, History Under Fire.

His passion for the theatre, for posing and artifice, is a fascinating undercurrent to the series of magnificent photographs undertaken in many theatres of war. Commissioned, after much lobbying on his own behalf, by the Ministry of Information, Beaton not only recorded the home front but travelled extensively in the Middle East, Burma, India, and China, finding in himself unexpected resources of physical stamina and mental resilience, although he was also understandably frequently exhausted and profoundly apprehensive. He was a dandy, appearing in best dressed lists, a snob, a narcissist, neurotic, needy and insecure. Yet however precious he was, he was also unremittingly hardworking, and surprisingly became the longest serving war photographer. He was not, however, a documentary reporter of the front line, however close he came to it.

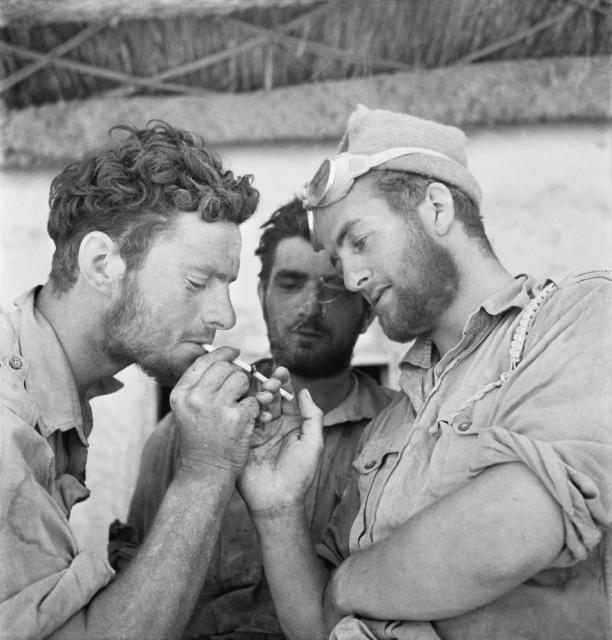

But from his behind the scenes vantage points, camps in the desert (pictured left, Long Range Desert Group, Libya, 1942), scenes of India and China, his exquisite taste and sense of the potentially dramatic made for visions which pointed not only to the human element but the vast and injured landscape which framed conflict.

But from his behind the scenes vantage points, camps in the desert (pictured left, Long Range Desert Group, Libya, 1942), scenes of India and China, his exquisite taste and sense of the potentially dramatic made for visions which pointed not only to the human element but the vast and injured landscape which framed conflict.

There are the remnants of the Raj just before its final expiration: in India, the Vicereine Lady Wavell, poses in court dress on the grand staircase of the Viceroy’s House in Delhi, in 1943, and the Princess of Berar in Hyderabad, as well as Lord Mountbatten, and the Sir John Colville, the governor of Bombay, in court dress. He had time for the picturesque, and was a very sophisticated tourist indeed, photographing boatmen on the Yangtze, Chinese actors, street musicians in India. The grittiest photographs are almost literally of sandstorms in the Western Desert, abandoned weaponry in Libya, and the encroaching jungle in Burma. Beaton, in this revelatory exhibition of the work of which he was most proud, shows us his astonishing skill in creating the most memorable and beautiful of compositions. But as magnificent and well laid as it is – replete with publications, letters, maps, videos, film clips – there is also a curious emptiness at its heart.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment